In Mat town, in South Sudan’s Jonglei State, Nyandeng Meeth was fetching water from a borehole one morning in the middle of April before heading home to cook for her nine children and open her small street stall.

Suddenly, the sound of gunfire and shelling tore through the familiarity and routine of the 50-year-old mother’s everyday life. She recalls how people frantically searched for their belongings, including their families, in a town that was thrown into chaos.

Meeth fled home without a trace because of her children. “I]had] left the children at home when I went to fetch water”, she said. When I returned home, there was no one I ran into. The nine siblings, ages 7 to 15, had fled along with the rest of the population.

The attacks, reportedly by Sudan People’s Liberation Army-in-Opposition forces (SPLA-IO), were part of a broader escalation in fighting between government forces – the South Sudan People’s Defence Forces (SSPDF) – and opposition troops, including the White Army group aligned with First Vice President Riek Machar.

More than 130, 000 people have been displaced by violence since late February in the Jonglei and Upper Nile states. Since then, aerial bombardments and fighter raids have emptied entire towns, hampered aid, and blocked important trade routes from neighboring Ethiopia.

The fighting is also prompting the country’s worst cholera outbreak in two decades, aid groups say, as patients fled medical centres where they were receiving treatment when the conflict broke out, spreading the disease in the process.

However, Meeth’s terror was rekindled by recent events, which occurred almost ten years ago when her husband was killed in a previous conflict.

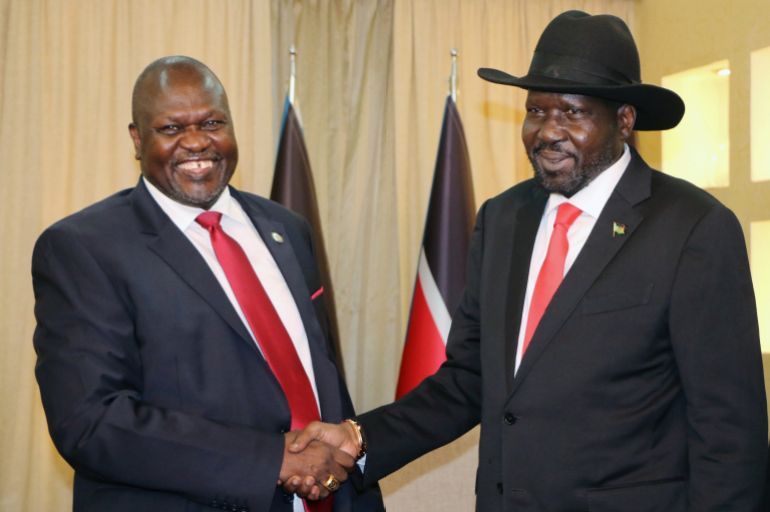

A civil war broke out between Machar-aligned forces loyal to President Salva Kiir in South Sudan in 2013, just two years after the country’s independence. The war killed an estimated 400, 000 people and displaced 2.5 million – more than a fifth of the population.

In 2015, Meeth’s husband, a soldier, was killed.

Although there was a peace deal reached between the conflicting factions in 2018, disagreements over how to carry out it, including delayed elections, have persisted.

Unresolved political disputes have driven cycles of violence over the years. However, things got worse this year, with Machar’s arrest and clashes between government forces and opposition fighter groups. The country may be in danger of waging a full-fledged civil war, according to a warning from the UN.

“My life in Mat was better,” said one participant.

More explosions rang out in Mat town on that mid-April day as Meeth, who had not yet located her children, rang out. She ran towards the Sobat River, where panicked residents scrambled to flee across to neighbouring Upper Nile State.

She noticed her 7th-year-old daughter running alone toward the riverbank in the crowd. Without knowing whether her eight other children, who were younger than her, had survived, she grabbed her hand and leapt into a canoe.

They landed in Panam, a town in Panyikang County in Upper Nile, about 2km (1.2 miles) from their home, where thousands of displaced families who have fled bouts of conflict from previous years are gathered, with little access to food, water, or medical care.

Meeth claimed that she was unable to eat or sleep there for two anxious nights. She remarked, “If your child is lost, you can’t be happy, even when I get food,” while sat beneath a coconut tree, which has since become her refuge.

Volunteers from the Panam community searched along the riverbanks and through the surrounding bushes for missing people. Eight of Meeth’s children were discovered after two days.

According to Meeth, “some of them hid in the river, while others hid under the shade of trees,” pointing out that her children could still hear gunfire from their locations, so they hid out of fear.

The ordeal had taken a toll on them. They had lost weight from hunger and exposure, and their bodies had become mosquito-bite-covered, she claimed.

Due to fighting that is still preventing aid access, she and her children are now sleeping under the coconut trees along the river. They are surviving on the roots of yellow water lilies and other wild plants.

Before the latest wave of violence, Meeth supported her family in Mat by selling tea, sugar, and other household essentials from an informal stall. When drought or floods caused the family to lose money, relatives who had been fishing would sometimes share their catch.

But what little she had has been taken away by the conflict. “My life in Mat was better because I had shelter, I had a mosquito net and shoes, and access to a hospital”, she said. She continued, “I had two goats but had to leave them,” citing Mat’s fugitives’ relatives who had informed her that the rebels had taken her livestock.

‘ Life is very difficult ‘

Before the most recent upheaval of fighting, there was hardship in South Sudan.

According to a recent World Bank report, nearly 7.7 million people are in crisis, emergency, or catastrophic levels of hunger, and 92 percent of the population is considered to be in poverty.

Not far from the Meeth family in Panam, 70-year-old Nyankhor Ayuel sat under the shade of another coconut tree with her seven children.

In Pigi County in Jonglei, they eluded Khorfulus in April.

“We and the kids were at home. We had already prepared food, and as we started eating, the shelling started”, she said. We didn’t have any food or luggage on our run.

Although they avoided the initial hostility, Ayuel claimed that hunger and illness now pose a different threat. Pregnant and nursing mothers, she said, are suffering from diarrhoea and vomiting due to lack of access to clean water and food.

She told Al Jazeera, “Life is very difficult. Our lodging lacks any amenities, such as food or medicine.

For families like Zechariah Monywut Chuol’s, who also fled Khorfulus, hardship has only deepened.

When the shelling started, the 57-year-old father of 12 was just beginning to build a permanent home for his family. When the foundation started to fall, I was at home digging it. We ran to the riverbank and got into canoes”, he said.

Chuol and his family now rely on coconut water and whatever fruits they can find along the Sobat River to survive, just like so many others in Panam.

He claimed that “many people would have already died if hunger could kill like sickness.”

A flimsy future

More than 9.3 million people in South Sudan, or three-quarters of the population, need humanitarian aid, according to the UN. Nearly half of them are children.

All aid efforts have come to an end because of the conflicts in Upper Nile and Jonglei. Aid organizations were forced to resign from their positions due to airborne bombardment and danger, shut down cholera treatment centers, and halt aid deliveries.

This weekend, the “deliberate bombing of]a Doctors Without Borders] hospital in Old Fangak” in Jonglei killed several people, the medical charity known by its French initials, MSF, said.

Due to limited access, the World Food Programme (WFP) stopped operations in a number of areas last month.

WFP’s South Sudan country director, Mary-Ellen McGroarty, said physically accessible places can be challenging at times. “But with active conflict, WFP cannot go up, we cannot go down the river. And these are the places where there are no cars, trucks, and roads, she claimed at the time of the UN press briefing.

More than 30 000 people who fled violence in Pigi County are now sheltering in displacement camps like Panam, where aid has yet to be found, according to Peter Matai, director of the government-run Relief and Rehabilitation Commission, which collaborates with international organizations to support internally displaced people.

“We’ve reported the situation to both the state government and international organisations”, said Matai. However, “aid organizations are still waiting for clearance from the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs to access displacement sites and deliver aid,” according to a statement released a few weeks after the fighting.

Thousands of displaced families are still living in limbo, caught between conflict, disease, and hunger; they are unsure when or if they will be safe to return home because the violence is still ongoing and access to humanitarian aid is limited.

For Meeth, who also serves as a deacon in the Episcopal Church of South Sudan, all she can do now is pray for her children’s safety, and hope that others will step in to help.

She claimed that “we are suffering.” We must hear that we are in a bad place from our neighbors who live abroad. They should help us provide for our needs”.

Source: Aljazeera

Leave a Reply