Four Black men were traveling from Port Elizabeth, now Gqeberha, to Cradock in South Africa on the night of June 27, 1985, in a car.

They had just finished doing community organising work on the outskirts of the city when apartheid police officials stopped them at a roadblock.

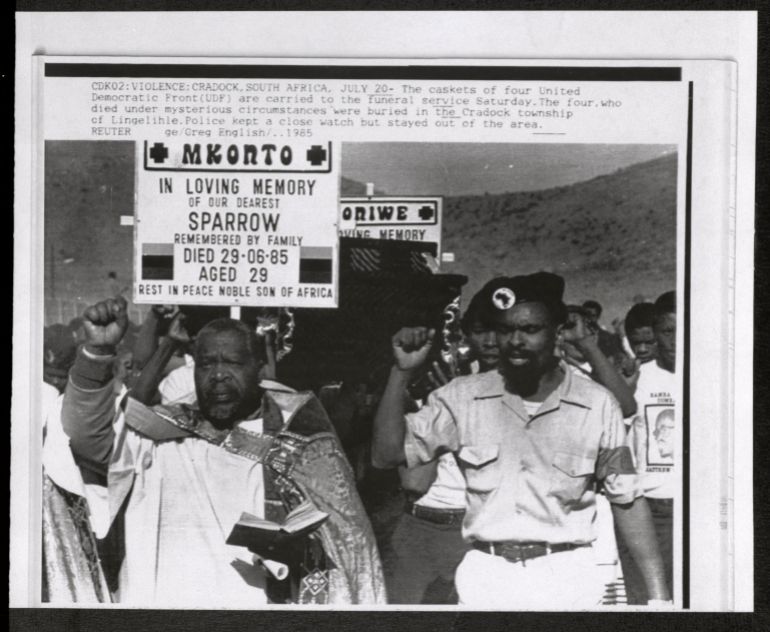

Fort Calata, 29, Matthew Goniwe, 38, Sicelo Mhlauli, 36, and Sparrow Mkonto, a railroad worker, were tortured and abducted.

Later, their bodies were discovered dumped in various neighborhoods of the city; they had been severely beaten, stabbed, and burned.

The police and apartheid government initially denied any involvement in the killings. The men were known to be under surveillance for their activism in response to the agonizing circumstances that Black South Africans faced at the time.

Soon afterward, it became clear that some of the group’s members had a death warrant, and that their murders had long been planned.

Though there were two inquests into the murders – both under the apartheid regime in 1987 and 1993 – neither resulted in any perpetrator being named or charged.

Early this month, Ford Calata’s son, Lukhanyo Calata, told Al Jazeera that “the first inquest was conducted entirely in Afrikaans.” The 43-year-old lamented that “my mother and the other mothers were never given any opportunity to make statements in that,” adding that.

“These were courts in apartheid South Africa. The courts said no one could be held accountable for the deaths of four people in a completely different time.

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) was established shortly after apartheid ended in 1994. There, hearings confirmed the “Cradock Four” were indeed targeted for their political activism. Although a few former apartheid officers admitted to being involved, they refused to provide more information and received no amnesty.

A new inquest has been launched four decades after the killings. Although justice has never seemed closer, for families of the deceased, it has been a long wait.

This week, Lukhanyo told the local media, “We have waited for justice for 40 years.” He said while speaking outside the court in Gqeberha, where the hearings are taking place, “We hope this process will finally expose who gave the orders, who carried them out, and why.”

As a South African journalist, it’s almost impossible to cover the inquiry without thinking about the extent of crimes committed during apartheid – crimes by a regime so committed to propping up its criminal, racist agenda that it took it to its most violent and deadly end.

There are many more victims like the Cradock Four, many more victims like the Calatas, and many more families who are still waiting to find out what really happened to their loved ones.

Known victims

I was reminded of Nokhutula Simelane when I watched the Gqeberha court proceedings.

I visited Bethal in the Mpumalanga province more than ten years ago to visit her family after her 1983 disappearance. Simelane joined Umkhonto we Sizwe (MK), which was the armed wing of the African National Congress (ANC) – the liberation movement turned majority ruling party in South Africa.

She served as a courier for messages and packages between Swaziland and what was then Swaziland as an MK operative.

Simelane was lured to a meeting in Johannesburg, where she was abducted, tortured, and disappeared before being taken into police custody.

Her family says they still feel the pain of not being able to bury her.

Five white men from what the apartheid police’s special branch applied for amnesty at the TRC in connection with Simelane’s alleged murder.

Willem Coetzee, the security police unit’s former commander, denies that she was the one who carried out the murder. But that was countered by testimony from his colleague that she was brutally murdered and buried somewhere in what is now the North West province. According to Coetzee, Simelane was later re-enter Swaziland after being turned into an informant.

No one has yet accepted responsibility for her disappearance, neither the ANC nor the apartheid security forces.

The case of the Cradock Four also made me think of anti-apartheid activist and South African Communist Party member, Ahmed Timol, who was tortured and killed in 1971 but whose murder was also covered up.

The 29-year-old teacher was being held in Johannesburg’s notorious John Vorster Square police headquarters when he fell from a 10th-floor window. The apartheid government was renowned for its lies and cover-ups, so an inquest the year after his death came to a conclusion.

Decades later, a second inquest under the democratic government in 2018 found that Timol had been so badly tortured in custody that he would never have been able to jump out of a window.

Former security branch officer Joao Rodrigues was only charged with Timol’s murder at that time. Given the number of years since Timol’s death, the elderly Rodrigues objected to the charges and requested a permanent stay of prosecution. He claimed that he would not be given a fair trial because he was unable to properly recall events at the time of his death. Rodrigues died in 2021.

A crime against humanity, in my opinion.

brutal apartheid. And for the people left behind, unresolved trauma and unanswered questions are the salt in the deep wounds that remain.

Which is why families like those of the Cradock Four are still seeking resolutions in court.

Nombuyiselo Mhlauli, the wife of Sicelo Mhlauli, 73, described the state of his body in her testimony to the court this month. He had more than 25 stab wounds in the chest, seven in the back, a gash across his throat and a missing right hand, she said.

One day before Lukhanyo’s court appearance, he was scheduled to continue his testimony in the murder hearing.

He described how crucially important the process had been in terms of emotion. He also spoke about his work as a journalist, growing up without a father, and the impact it’s had on his life and outlook.

“Our humanity was targeted,” the statement read. On the sixth day of the inquest, Lukhanyo testified that the state in which my father’s body was discovered was a clear crime against humanity in all respects.

But his frustration and anger do not end with the apartheid government. He attributes too much time to the ANC, which has been in power since the end of apartheid, to failing to adequately address these crimes.

Lukhanyo claims that the ANC’s betrayal of the Cradock Four “cut the deepest” in its own opinion.

“Today we are sitting with a society that is completely lawless”, he said in court. This is because, at the beginning of this democracy, we did not establish proper procedures to inform the rest of society that you would be held accountable for what you had done wrong.

From 1939 to 1949, Fort Calata’s grandfather, Reverend Canon James Arthur Calata, served as the ANC secretary-general. The Calata family has a long history with the liberation movement, which makes it all the more difficult for someone like Lukhanyo to understand why it’s taken the party so long to deliver justice.

pursuing justice and peace

According to Mmamoloko Kubayi, the minister of justice and constitutional development in South Africa, the government has increased its efforts to provide families with long-awaited justice and closure.

“These efforts signal a renewed commitment to restorative justice and national healing”, the department said in a statement.

The Cradock Four, Simelane, and Timol are just a few of the horror stories and murders we are aware of.

But I frequently wonder about all the names, victims, and testimony that are still unidentified or buried.

The murders of countless mothers, fathers, sisters, brothers, sons and daughters by the apartheid regime matter not only to those who cared for them but for the consciousness of South African society as a whole, no matter how normalised the tally of the dead has become.

How long will this new inquest take, it’s not certain. Former security officers, political figures, and forensic experts are expected to give testimony during the course of several weeks.

Initially, six police officers were implicated in the killings. Although all of them have since passed away, the Cradock Four’s family believes senior authorities should be held accountable for the orders they were given.

However, the state may be reluctant to foot the bill for the legal expenses of the apartheid police officers who are convicted of the murders, which could stifle the investigation.

Meanwhile, as the families wait for answers , about what happened to their loved ones and accountability for those responsible, they are trying to make peace with the past.

Source: Aljazeera

Leave a Reply