We examine other bands that have lost due to money as The Police battle it out in a royalties dispute in the High Court.

Performing to sell-out stadiums all over the world in their 1980s heyday, The Police were one of the biggest bands on the planet.

Offstage, however, there’s been disharmony between lead singer Sting and his former bandmates Stewart Copeland and Andy Summers – who have made it clear every pound you take matters when it comes to royalties.

Millions have been made from top hits like Message in a Bottle (1979), Every Little Thing She Does Is Magic (1981), and Every Breath You Take (1983).

But frontman Sting is said to owe more than $2m (£1.5m) in ‘arranger’s fees’ to drummer Copeland and guitarist Summers, but has told the High Court in London he’s already paid more than £500K to them since they started legal proceedings.

READ MORE: Brian May’s wife makes home life admission after countryside move

The issue is largely stemmed from how to interpret various agreements and how they apply to streaming, which was unaffected when The Police were founded but still generates significant income for the group, which underwent a successful global tour in 2007 after being publicly disbanded in 1984.

Later, drummer Copeland later revealed that the trio “beat the crap out of each other” while “very dark” recording sessions for Synchronicity, their penultimate album.

And their ruckus is not the only one to reach a dramatic crescendo in rock ‘n’ roll.

A similar case involving the estates of Jimi Hendrix Experience bassist Noel Redding and drummer Mitch Mitchell is expected to result in a verdict next month. The case involves copyright, unpaid royalties, and performers’ rights to recordings from streaming revenues, including those from the likes of Are You Experienced, Axis: Bold as Love, and Electric Ladyland.

Roger Waters and David Gilmour’s involvement in the fallout of Pink Floyd was also related to a dispute over royalties in the past. Waters, who authored the majority of the lyrics and concepts for albums like The Wall (1979) and The Final Cut (1983), claimed to be the main creative force behind Gilmour’s focus on musical arrangements and guitar solos. The Wall and other works’ conceptual rights were reclaimed by Gilmour and Nick Mason, while Waters and Gilmour and Nick Mason were granted the Pink Floyd name.

The Smiths, whose hits included 1984’s I’m Miserable Now, split in 1987 as a result of disagreements between Morrissey and Johnny Marr regarding musical direction. However, drummer Mike Joyce and bassist Andy Rourke filed lawsuits against their fellow bandmates in 1996 for unfair royalties distribution. Morrissey and Marr were only paid 40% of the band’s profits, while Mike and Andy only received 10%, and a judge eventually granted the rhythm section back royalties of £1 million and 25% going forward. According to Morrissey, “the court case was a potted history of the life of the Smiths,” denying any chance of a reunion.

Surfin USA may have been the song that later brought the Beach Boys to fame in 1963, but it cost Capitol Records over $2 million in unpaid royalties and production costs. The Beach Boys’ manager, Murry Wilson, gave Berry the rights to the song’s publishing royalties in exchange for the song’s melody, which was taken from Chuck Berry’s Sweet Little Sixteen. And it did not end there. In the middle of the 2000s, Mike Love claimed that a free promotional CD had cost him millions in royalties after he sued his cousin Brian Wilson and Brother Records. Wilson’s wife, Melinda Wilson, said at the time that Wilson had told his cousin to “you better start writing a real big hit, because you’re going to have to write me a real big cheque.”

Tony Hadley, Steve Norman, and John Keeble filed a lawsuit against their former Spandau Ballet bandmate, Gary Kemp, for a share of publishing royalties in 1999, alleging they had contributed to the arrangement of the band’s songs. Gary Kemp described the case as “gold,” saying, “I view this as a victory for all songwriters.” It was a “serious lesson” for musicians to ensure they were hired, according to Loser Hadley. He remarked, “I don’t believe anyone can enjoy going to court to fight it out with their former best friends.”

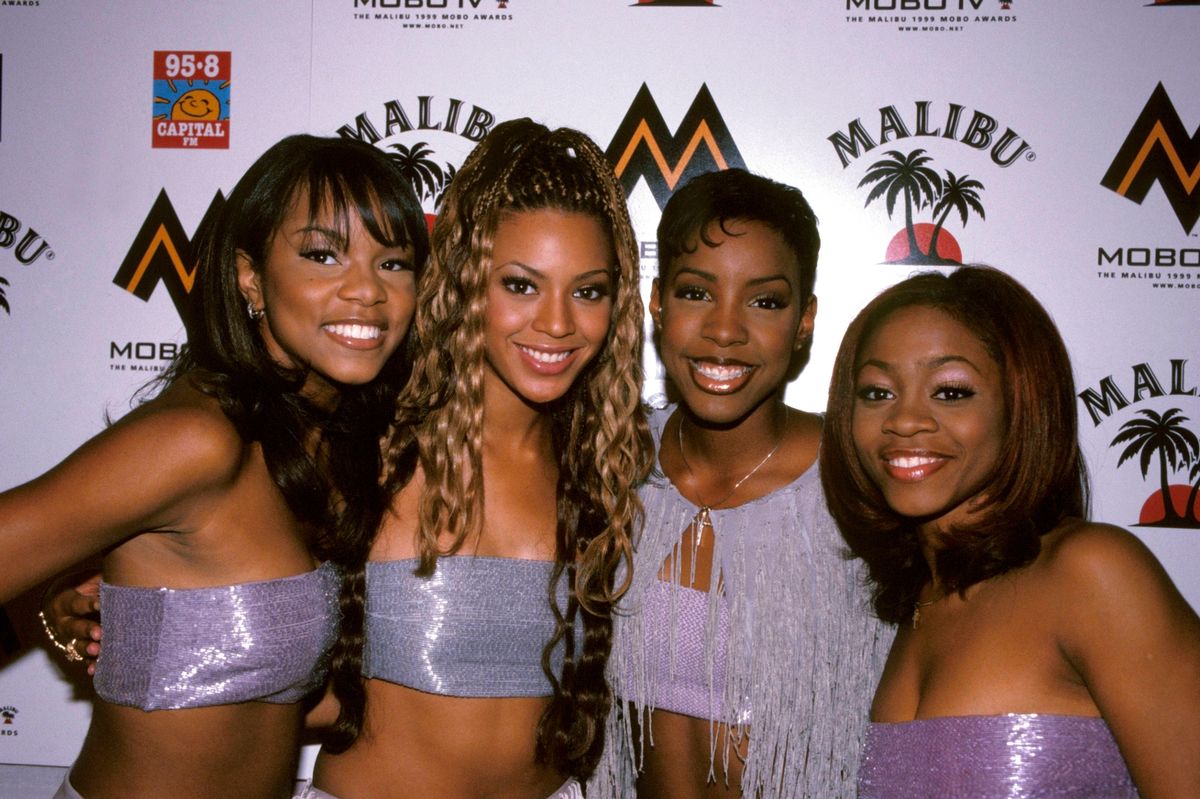

LeToya Luckett and LaTavia Roberson, both from Destiny’s Child, allege their manager Matthew Knowles made money off of their work in 2000 and that they received hardly any compensation. Although the case was ultimately resolved in the absence of a judge, it sparked disagreements among the band’s members.

When the rest of the band reformed without bassist Peter Hook in 2011 after he unceremoniously announced that New Order would split in 2007, a massive legal battle erupted over the use of the band name and the distribution of royalties. Hook once said, “We’re a bunch of fat old men arguing.” We are all happy to keep going, despite how pitiful it is.

The Black Crowes’ split in 2015 was also the result of a royalty dispute. Chris and Rich Robinson were sued by Drummer Steve Gorman, and the case was settled in vain in 2022. Steve Gorman went into great detail about his long-standing feud with the band over unpaid royalties in his memoir, Hard to Handle, but Rich refrained from making such claims.

Mark Beaumont, who writes for NME (New Musical Express), says, at the end of the day, these rows over royalties are only rock ‘n’ roll. He tells The Mirror: “Once bands have put in a lot of the same hard groundwork as each other, in terms of touring and recording to build a successful group, and also developed their little niggles and annoyances with each other in the van, it’s usually money that eventually drives them apart.

When a singer and guitarist dedicate their lives to the band and put in just as much effort on tour, the other parties get upset because they see them getting a bigger cut for the extra time and talent they put in to write the songs. They frequently believe that their studio contributions to the chorus hook are less valuable but still have an even greater significance than their bass, drum, or keyboard contributions.

Mike Joyce and Andy Rourke are a prime example of this because they believed they were no better than session musicians despite making a significant contribution to the band’s music’s sound and style despite receiving a 10% performance and recording revenue from Morrissey and Marr.

The songwriters now make the majority of the band’s income from syncs, streams, and radio play, which is what they call “. Within the same band, it can result in haves and have-nots. Why do bands like Coldplay, who also share their publishing rights, continue to work together for a long time while the gaps start to appear in many other bands as soon as the money starts to rise.

READ MORE: Dunelm reduces ‘hotel quality’ bedding sets with prices from £7 in January sale

Source: Mirror

Leave a Reply