Iran’s economy is experiencing rapid economic decline and grievances over multiple ongoing crises, prompting protests and strikes to spread throughout Iran over the past week.

Shopkeepers took to the streets and closed down businesses in downtown Tehran on December 28, sparking demonstrations , that have now been recorded in most of Iran’s 31 provinces.

Recommended Stories

list of 4 itemsend of list

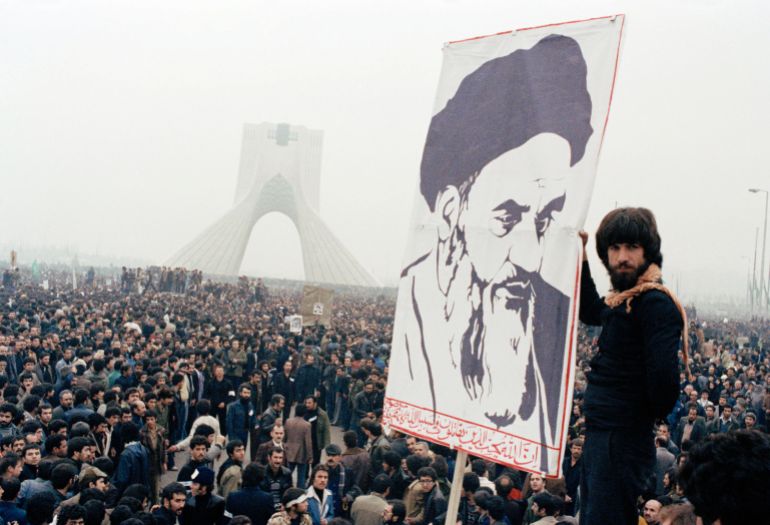

The country has a long history of popular protests over a range of issues, and the Islamic revolution that brought the country’s governing theocracy to its feet in 1979 saw its final shah toppled.

Here’s a look at previous nationwide and some smaller protests after the revolution and how they were handled to offer a fuller picture of what is transpiring now.

protests in the early years of the post-revolution (1979-late 1990s)

Women’s protests started less than two weeks after the revolution, with thousands marching in Tehran to oppose Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini’s decree mandating the hijab, or Islamic headscarf covering.

Following the decree, there were restrictions on radio and television music broadcasting, a ban on alcohol, and the separation of men and women in schools, pools, and beaches.

The alarmed women were met with threats as well as pro-state mobs who attacked them with sticks and stones. The Islamic Republic’s pillar and the source of decades of tensions with the public culminated in the Mahsa Amini protests of 2022 and 2023 when the hijab eventually became required and noncompliance was later made legally illegal.

As differences grew among camps that led the revolution to success, the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) was formed and deployed to crack down on protests and political dissent called by opposing camps, especially the Mojahedin-e-Khalq (MEK) and their supporters.

The MEK eventually turned to bombings and assassinations, and the establishment later labelled it a “terrorist” outfit. Many members were executed or exiled, predominantly during the final years of the devastating eight-year war with neighbouring Iraq, which invaded Iran under Saddam Hussein in the 1980s.

Only occasionally occurring unrest was reported in Mashhad in 1992, Qazvin in 1994, and the Eslamshahr suburb in Tehran in 1995, largely due to economic grievances and sudden price increases, during the remainder of the 1990s.

Protests involving students and reformers (1999-2003)

In July 1999, Tehran was rocked by massive student-led protests triggered by the closure of a reformist newspaper by hardliners.

Students who supported President Mohammad Khatami’s alleged liberalization and reforms agenda and his “dialogue among civilisations” discourse to strengthen international ties were outraged by the media censorship.

Police and paramilitary Basij forces affiliated with the IRGC raided the dorms of the students at night and brutally attacked them in their sleep, beating them and even reportedly setting rooms on fire.

Tehran’s population and students took to the streets, and the demonstrations spread to universities in Tabriz, Mashhad, Isfahan, and other cities.

By the time the protests were quelled by security forces days later, multiple students were dead, dozens injured, and hundreds jailed.

None of the security forces involved in the hostility were chosen, according to the judiciary, for placement. One police officer was ordered to pay a fine for stealing an electric shaver. After his election, Khamenei only lamented “riots” that allegedly sought to derail his reforms and expressed his strong support for Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei. He has been sidelined for years like all other presidents.

The issue also received international attention, with a picture of a student holding up the bloodied shirt of his friend going viral.

Leaderless student protests were resurrected shortly after the initial demonstrations in 2003, but they were halted for about a week due to clashes and arrests.

In late June 2007, public anger erupted overnight in Tehran and cities across the country after populist President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad imposed an abrupt petroleum rationing scheme to curb imports, which led to people forming long queues at fuel stations.

Before calm was largely restored a day later, protesters reportedly set a number of fuel stations and some bank branches on fire.

Green Movement (2009-2010)

After the June 12 presidential election, when the hugely divisive Ahmadinejad was re-elected to form a second government, Iran saw by far its largest protests, which also grabbed international attention.

After the authorities insisted Ahmadinejad won in a landslide, millions of Iranians gathered in Tehran and other major cities across the country. Protesters, some donning green attire used as the campaign colour of reformist candidate Mir Hossein Mousavi and his allies, formed peaceful protests of unprecedented scale, asking, “Where is my vote”?

However, Basij militias and police began using batons, tear gas, and eventually live ammunition to attack rallies after weeks of demonstrations. Dozens were confirmed killed by human rights monitors, but the authorities refused to announce official death tolls.

Neda Agha-Soltan, a young woman’s death, shook the country and made her a global icon. The 26-year-old philosophy student was filmed bleeding on the pavement in Tehran after being shot in the chest while protesting, with blood pouring out of her mouth and nose.

State television and law enforcement tried to persuade Agha-Soltan’s parents to support their version of events, but they were turned down by eyewitnesses’ claims that the security forces shot her. They also claimed the video was fabricated using “propaganda” at work to turn people’s opinions.

The protests eventually stopped in early 2010 after several thousand people were arrested, partial media blackouts imposed, and internet and mobile networks throttled. Later, Mousavi was placed under house arrest, and he is still confined to his current position. The authorities have said they consider the Green Movement not as legitimate dissent, but as a “sedition”.

The Green Movement’s impact on Iran’s internet grew significantly as a result of the blockade of numerous top international services, including Twitter, Facebook, and YouTube, as well as of thousands of websites.

In early 2011, several Iranian cities saw solidarity protests with Arab Spring demonstrators in Egypt, Tunisia and other countries. After the Iranian rial lost more than 60% of its value to the US dollar in a few weeks, there was a surprisingly large demonstration and strike in Tehran’s Grand Bazaar in October 2012.

Overt street protests were limited between 2013 and 2015, when moderate President Hassan Rouhani came to power with the promise of decreasing tensions with the West and improving people’s livelihoods hurt by United Nations sanctions imposed over Iran’s nuclear programme.

In the final days of 2017, a few hundred demonstrators started chanting slogans against the government of Rouhani over economic hardship in the northeastern ultraconservative city of Mashhad.

As Iran’s currency fell as a result of US President Donald Trump’s threats to withdraw from the landmark nuclear deal reached with world powers in 2015 and impose sanctions, this occurred in the middle of a political conflict between reformists and hardliners.

Within days, the protests spread to more than 100 cities across the country, with people chanting against the establishment amid anger over the cost of living, unemployment, and regional policies such as funding and arming the so-called “axis of resistance”.

After weeks of protests, a total of 69 people were killed, with many more still being detained. Most of the protesters were shot in provincial towns. The government also blocked Telegram, the messaging app that continues to remain vastly popular in Iran despite years of online crackdown.

In Iran, truck drivers nationwide launched strikes over low wages and fuel costs throughout 2018 as a result of that upheaval. Teachers and educators organised sit-ins and peaceful rallies in most provinces to demand unpaid salaries and better funding for schools.

People took to the streets in western Khuzestan province in the summer of 2018 only to be met by security forces who shot live rounds and pellets, killing and wounding a number of people.

There were also environmental demonstrations, with farmers in central Isfahan protesting the diversion of water from the iconic Zayandeh Rud River, at times blocking roads with tractors.

In November 2019, the government’s overnight increase in petroleum prices sparked another tense event that sparked a sudden wave of nationwide protests.

People began chanting in Tehran and closing down highways during the winter cold. In the capital and in other places like Mahshahr in Khuzestan, Iranians from all walks of life, especially the working-class and strained youth, enlisted.

Within days, IRGC units and riot police fired live ammunition, water cannon, and tear gas to put an end to demonstrations in city after city.

Iran’s first-ever near-total internet blackout, which left tens of millions of people without a connection for close to a week, was a major shock to Iranians.

Amnesty International said at least 304 protesters were killed, but Reuters news agency cited an unnamed Interior Ministry official as saying the death toll was closer to 1, 500. A parliamentary report only acknowledged about 230 deaths as a result of the government’s months-long refusal to release any official casualty statistics.

There were smaller aftershocks and new triggers over the next two years, with demonstrations recorded over the IRGC’s downing of Ukraine International Airlines Flight PS752 with two missiles and officials ‘ denial of the incident for days, along with more water protests in Khuzestan and farmers ‘ strikes in Isfahan.

(2022-2023) Mahsa Amini uprising

Millions across Iran once more expressed their anger and desire for change across the country after 22-year-old Mahsa Amini died in police custody after being arrested for alleged noncompliance with mandatory hijab rules.

She died while collapsing at a “re-education center” in Tehran where she was taken by police while leaving a metro station to take a vacation with her family. Authorities insisted she had a stroke and suffered from pre-existing health conditions, but her family said she may have been beaten.

Concerning issues like women’s rights, which were the focus of months of protests in streets and universities, as well as deteriorating economic conditions and extremely limited personal, social, and internet freedoms,

“Woman, life, freedom” became a main slogan, and many people took off their headscarves and switched to their attire of choice in the aftermath, openly defying the “morality police” and hardliners calling for punishments and passing a draconian hijab law.

Huge demonstrations, sometimes gathering as many as tens of thousands, formed in countries around the world in support of the protests as well. Many emphasized the recognition of young Iranians who had died in the protests.

Authorities once more traced “enemy” hands to the unrest, especially those of the US, its Western allies, Israel, and even Saudi Arabia, and said “rioters” would face the harshest punishments.

In connection with the unrest, hundreds of protesters were killed, more than 20 000 people were detained, and several people were put to death, with at least one being publicly hanged from a crane in Mashhad to deter others.

Most of the protests over the years have been leaderless, meaning no single or determined group of organisers has emerged, even as foreign-based individuals and entities continue to claim partial leadership and oppose the establishment without enjoying broad public support inside Iran.

Source: Aljazeera

Leave a Reply