When the fever strikes, Abdul Hadi Nadir’s tiny body quickly dries up in Karachi and Lahore, Pakistan. His skin turns yellow, he stops eating, and his mother, Rimsha Nadir, knows exactly what that means – it is time for more blood.

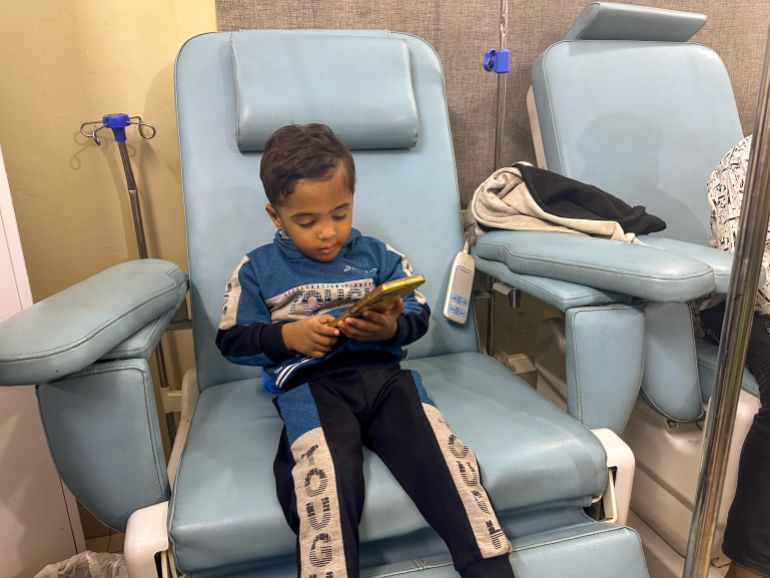

Rimsha cradles her three-year-old son while sat among other families with children at a quiet but crowded clinic in Lahore.

Abdul Hadi is one of the youngest in the room. Children are seated quietly in front of him, some restrained from receiving blood from their IV drips. Nearby, a mother sits at the foot of her 12-year-old son’s reclining chair, gently massaging his leg.

Rimsha places her son in front of her, giving him her cell phone. The toddler is momentarily distracted by a video on what will be a long day of having to stay still.

Rimsha is hoping that a blood transfusion will help her son, if only temporarily, recover.

“After he gets]the blood]”, the 22-year-old says softly, “then he eats everything”.

Rimsha is well aware of her routine, which includes monthly visits from morning until evening and the emotional strain of watching her child sway between ill and surviving.

At just nine months old, Abdul Hadi was diagnosed with beta thalassaemia major – the severest form of a genetic blood disorder that causes the body to produce abnormal haemoglobin, resulting in chronic anaemia. The only known treatment for the condition is blood transfusions, which are necessary.

Rimsha had known about thalassaemia before her son’s diagnosis. At the age of nine, her husband’s nephew perished from it. His parents were not able to bring him into the clinic for regular transfusions, and before he died, he required a new transfusion every three days.

Rimsha holds onto hope for the future of her child despite this. “He will study, he will become a doctor, God willing”, she says in a soft voice.

There are about 100,000 registered thalassaemia major patients in Pakistan, and more than 5, 000 children are born with the condition each year. However, it is unknown how many of these people pass away. But in a country where the average lifespan for a child born with the disease is just 10 years, families like Rimsha’s are caught in an endless cycle of securing regular blood transfusions.

Genetic disorder

The “thalassaemia belt” includes parts of Africa, the Mediterranean, the Middle East, the Indian subcontinent, Southeast Asia, Melanesia, and the Pacific Islands, which has a high prevalence of the disease that spans the region.

This high prevalence could be a genetic response to protect against malaria, according to researchers. In areas where malaria is or was prevalent, the condition is more prevalent.

Thalassaemia major is the most common genetic disorder in Pakistan, according to a European Journal of Human Genetics study in 2021.

Only after their son was diagnosed did Rimsha and her husband realize they were carriers of the disease. As carriers, they have the thalassaemia trait or thalassaemia minor, meaning they have a mutated gene on a chromosome inherited from their mother or father. The mutation originated from both parents in those who have thalassaemia major.

The Pakistani NGO Fatimid Foundation estimates that the carrier rate for thalassaemia and other blood disorders ranges from 5 to 7 percent, according to the country’s Fatimid Foundation, which operates blood banks and treatment facilities. This translates to about 13 to 18 million carriers in the country of more than 251 million.

Carriers don’t spread the disease and are typically asymptomatic, but they can still give birth to a child who would need blood transfusions for the rest of their lives.

“If both parents are carriers, in every pregnancy there is a 25 percent chance that a child is born with thalassaemia major”, says Dr Haseeb Ahmad Malik, the medical director of the Noor Thalassemia Foundation, where Abdul Hadi and others receive free transfusions.

The doctor explains that a pregnancy between two carriers has a 25% chance of producing a baby with no mutated gene, and that the child’s offspring has a 50% chance of carrying the disease.

![Dr Haseeb Ahmad Malik [Urooba Jamal/Al Jazeera]](https://i0.wp.com/www.aljazeera.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/IMG_0344-1758537619.jpg?w=696&ssl=1)

gathering the family to distribute blood

Malik walks through the long corridor where children receive their transfusions, many of them gazing silently ahead, greeting his young patients. At the sight of him, Abdul Hadi chuckles and laughs, and he is familiar with all of them.

For Rimsha and her husband, the journey by car to the clinic takes half an hour. However, the journey can be lengthy and exhausting for many of Malik’s patients who reside in Lahore’s remote areas and use unreliable public transportation. Most treatment centres in Pakistan are situated in big cities, limiting access for people in rural areas, says Malik.

Blood is frequently short in Pakistan, even for those who regularly have access to clinics. Donations tend to decline significantly during the fasting month of Ramadan, extreme weather events, and crises such as the COVID-19 pandemic, the doctor explained.

Access has gotten better over the years, though.

One of the country’s first volunteer blood donation systems was established by the Fatimid Foundation in 1978.

Moinuddin Haider, a retired Pakistani army general and former interior minister from 1999 to 2002, quotes Moinuddin Haider, chairman of the foundation as saying “distant people would sell their blood outside hospitals.”

Haider’s older brother, who was also in the army, had two sons with the disease.

When he would return from his army posts, Haider would gather the family and ask for blood, which Haider, in an interview with Al Jazeera in Karachi, explains. “We used to wonder what kind of disease is this that requires all of us to donate blood.”

Only one of those nephews is alive today at 40, he says. He continues, adding that in recent years, many people have died in early childhood because of NGOs working to control the disease.

“Their lifespan has increased. They are getting married right now, he says, adding that his foundation encourages patients to continue to study and work without being constrained by their condition. “We have come a long way”.

![Muhammad Ahmad Dildar [Urooba Jamal/Al Jazeera]](https://i0.wp.com/www.aljazeera.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/IMG_0400-1758537688.jpg?w=696&ssl=1)

A future without dreams

After 2 p.m., Muhammad Ahmad Dildar is waiting for his turn to receive the blood that keeps him alive at the Noor Foundation.

The 22-year-old introduces himself with a toothy grin as he sits in Malik’s office.

Muhammad has been visiting the clinic alone for the past nine years. He says his parents – who are first cousins and carriers of the disease – instilled in him the discipline to do so.

Muhammad has never missed an appointment since receiving his diagnosis at the age of three months.

His parents were punctual with giving him the medication he needed to remove excess iron from the blood transfusions to avoid organ damage.

According to Malik, “He and his parents put a lot of effort in,” adding that Muhammad’s parents also request blood donations when supplies are short at the clinic.

Muhammad is among his “most compliant” patients, he says, explaining how a patient’s efforts are key to ensuring a longer life. Many people in Pakistan are unable to seek out adequate care due to a lack of education or awareness, he claims.

Muhammad comes to the clinic twice a month, making the 15-minute trip in the car he uses for work, driving for a local ride-hailing app.

When symptoms reappear, he is aware that a visit is necessary.

“My blood pressure gets low, I get a fever, I have back pain”, Muhammad explains, brushing his hair out of his eyes as he speaks. He makes a pause. “Life is very tough”.

One of five siblings who has the illness is the only one. Without the transfusions, he is vulnerable to a range of infections, bouts of which have already left him bedridden for more than six months at a time and forced him to drop out of school in the ninth grade.

Muhammad is aware that Pakistan’s average lifespan for thalassaemia major patients has already exceeded that of Muhammad.

His face darkens when he is asked about his future. He says, “Sometimes I’m very afraid,” his voice trembling. “I feel like I can die at any time”.

He claims he is grateful that he is still alive and doesn’t make any future plans.

“I’ve never thought about any dreams for myself … nothing at all”, he says. “I’ll just keep getting my blood and living,” the saying goes.

![Pakistan blood disease story [Urooba Jamal/Al Jazeera]](https://i0.wp.com/www.aljazeera.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/IMG_0378-1758537659.jpg?w=696&ssl=1)

seeking a solution

Thirteen-year-old Mudassir Ali grew up a few hours north, in Pakistan’s third-largest city of Rawalpindi.

At the age of 16 months old, he was given the diagnosis of thalassaemia major.

“I couldn’t play like regular kids”, he recalls in a phone interview. “I would get tired more easily and lose my breath more easily.”

A photo of Mudassir as a toddler shows him hooked up to multiple cannulas, the sleeves of his fuzzy pink and yellow hooded sweatshirt rolled up for the plastic tubes that run from his wrists, chest and abdomen.

However, he hasn’t needed these devices for years because he is one of the few people in the nation who has received a bone marrow transplant to cure his thalassaemia.

While many transplants in Pakistan occur on thalassaemia patients, the number of operations remains low due to a lack of funding and resources, according to a 2023 study in the Journal of Transplantation by the Pakistan Bone Marrow Transplant Group.

According to the study, 88 transplants were performed on patients with thalassaemia in 2022, compared to 118 in 2021.

Mudassir was four years old when he received a transplant.

Muhammad Naeem Anjum, the son’s father, made a promise to cure him when he was diagnosed.

“I had one mission, to get my son better”, says the 44-year-old government employee.

As Mudassir went through test after test, the father of six spent years shepherding his son from doctor to doctor.

Eventually, he learned about the transplant option – the only, if risky and costly, cure.

According to Anjum, “I visited three doctors, and they said there was an 80% chance that the [transplant] could be successful.” “As he gets older – like 14, 15 years old – the chances]of success] would have reduced to 60 percent or less”.

As the risks increase with age, Dr. Syed Waqas Imam Bokhari, the lead physician for bone marrow transplants at the Shaukat Khanum Memorial Cancer Hospital and Research Center in Lahore, believes that young children with thalassaemia are most successful because of the risks they pose.

The procedure involves replacing the body’s faulty blood-forming stem cells with healthy ones from a donor taken from the pelvic bone or bloodstream. Before the donor cells are introduced into their bloodstream, the patient goes through myeloablation, where bone marrow is often replaced with new cells, frequently through chemotherapy, as in Mudassir’s case. These cells then find their way to the bone marrow and, if successful, produce new healthy blood cells.

![Mudassir Ali [Courtesy of the Ali family]](https://i0.wp.com/www.aljazeera.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/IMG_20160405_191852_511-1758537573.jpg?w=696&ssl=1)

‘ He will get better ‘

However, the procedure involves risks.

Infections are a potential complication. According to Bokhari, graft failure can occur in five to 10% of cases of patients under the age of seven. “The blood counts do not recover with the new cells and the older cells come back, or the blood counts recover, but then … they go down again”, he explains, adding that the likelihood of this happening also increases with age.

Graft-versus-host disease, where new cells that are a part of a new immune system “mount a reaction against the host,” according to Bokhari. Graft rejection, meanwhile, is the inverse, where the patient’s immune system attacks the transplanted cells.

Anjum looked into the cost of the procedure as the family waited patiently for him to return to the hospital where they watched him while he slept during his nighttime transfusions.

In 2014, doctors in Karachi, where he travelled occasionally for work, quoted him 2.4 to 2.6 million rupees (approximately $23, 000 to $25, 000 at the time) for the procedure. The cost is closer to 5 to 7 million rupees (roughly $ 17, 600 to $ 24, 700), according to Bokhari, given the country’s economic downturn and the rupee’s declining value.

These costs are out of reach for most in Pakistan, where the gross domestic product (GDP) per capita is less than $1, 500, according to 2024 World Bank figures.

However, a doctor advised Anjum to examine the procedure at a military hospital in Rawalpindi, where the cost was a little less expensive, and where his work would pay 80% of the cost.

Anjum remained determined, even as relatives and friends with children with the disease discouraged him, calling it a financial drain and insisting children like Mudassir never fully recover.

He recalls being told by them, “You’re wasting your money.”

“I said, ‘ God willing, he will get better'”, Anjum says.

Then, it was time to find a donor.

![Mudassir and Musaddiq Ali [Courtesy of the Ali family]](https://i0.wp.com/www.aljazeera.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/IMG_20160323_081224_777-1758537553.jpg?w=696&ssl=1)

a true match.

The biggest risk in transplantation is graft rejection, says Bokhari.

There is only one gene that allows one person’s immune system to be nearly identical to another, he says. This is a syngeneic twin, or identical twin.

In transplant procedures, then, finding a donor with a closely-matched human leukocyte antigen (HLA) gene – critical for immune system regulation – is essential, says Bokhari. He continues, “Siblings are frequently the most compatible matches.”

“For each sibling, there’s a one in four chance that we’ll find a fully matched donor”, says the physician.

Finding an unrelated donor who matches a patient is possible in situations where the patient has no siblings or when no sibling is a match. But in Pakistan, which does not have large and well-established donor registries, it is almost impossible, says Bokhari.

He continues, “There are enormous registries in the West.”

Two of Mudassir’s siblings turned out to be good matches. One of them, Musaddiq, his brother, who was then nine, was a perfect match.

Mudassir received his bone marrow transplant in April 2016. He started to improve the day after his operation. Nearly a decade later, Mudassir has made a full recovery. Since the transplant, he hasn’t needed a single blood transfusion.

Anjum’s voice catches as he remembers a moment, not long after the operation, when Musaddiq told him, “Now that our brother is better, he can play with us”.

Mudassir wants to work as a doctor one day so that other kids can have the same second chance at life. “Others should be able to get the surgery too”, he says.

![Pakistan blood disease story [Urooba Jamal/Al Jazeera]](https://i0.wp.com/www.aljazeera.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/IMG_0419-1758537707.jpg?w=696&ssl=1)

Burden on families

However, it is simply beyond the power of a bone marrow transplant to cure thalassaemia major in Pakistan’s thousands of children and young people like Abdul Hadi and Muhammad.

Some charity-run hospitals and organisations offer free bone marrow transplants, but the number they can perform each year is limited by available funding, Bokhari explains.

For instance, 71 bone marrow transplants were performed at his own donor-supported hospital in 2024, of which only one was performed for a patient with thalassaemia major.

Furthermore, the doctor points out, the 12 transplant centres in the country are not enough to meet the needs of transplant patients.

He claims that it doesn’t match at all, which is why.

Malik of the Noor Foundation believes there should be a national campaign to push for premarital screenings – done via blood tests – among couples to test for the disease-carrying gene.

This could aid couples in making informed choices, whether it’s choosing to avoid getting married to a different carrier or making early plans for a potential child with thalassaemia major. There are some screening programmes in the country’s four provinces, but Malik says many times, if a couple finds they are both carriers of the disease, it does not impact their decision to marry or have children, particularly when it is an arranged marriage.

If a marriage is fixed, “they won’t break their commitment,” he says. “Family bonds are very strong here.”

For now, parents of the thousands of children with thalassaemia major across Pakistan shoulder the burden of managing the disease as they seek out blood transfusions to keep their children alive.

Source: Aljazeera

Leave a Reply