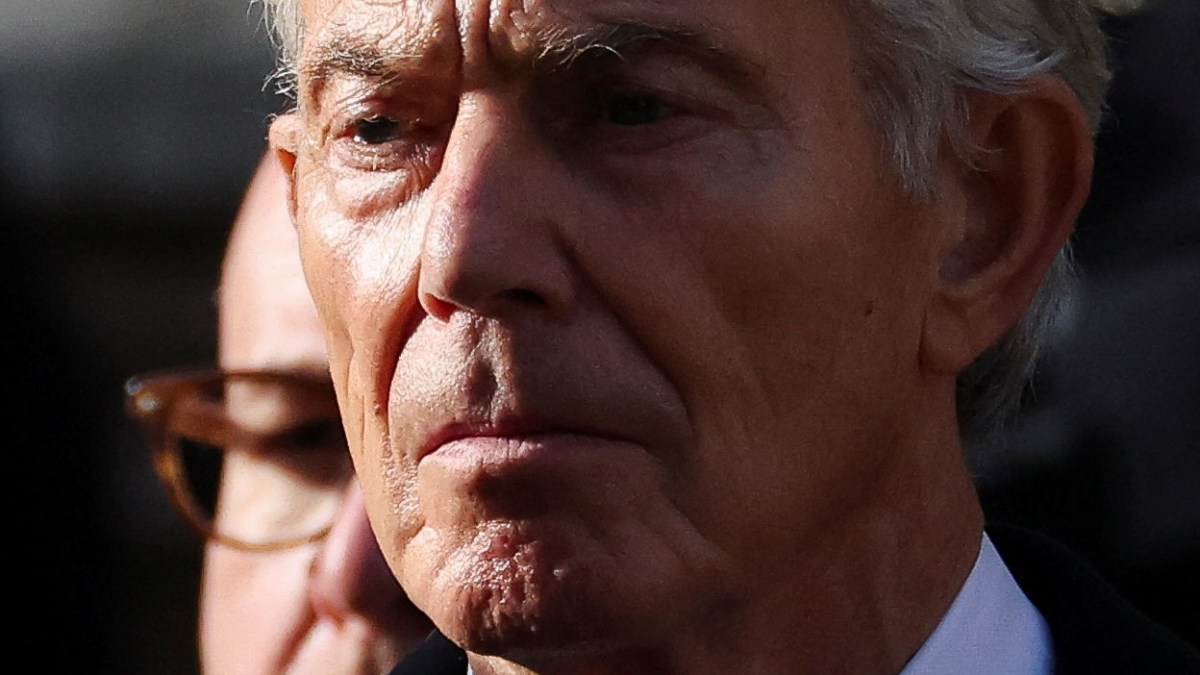

Many actors involved in negotiations to end Israel’s genocidal war on Gaza and begin its reconstruction breathed a collective sigh of relief when it was announced that former British Prime Minister Tony Blair, one of the most polarising figures in international diplomacy, was removed from the proposed “board of peace”, tasked with overseeing the transitional phase in the Strip. The announcement came at a highly sensitive moment, just as negotiations entered their second phase, focused on the security and economic arrangements necessary for stabilising the Strip and launching reconstruction efforts.

United Nations Security Council Resolution 2803, adopted on November 17, 2025, and aligned with United States President Donald Trump’s Gaza peace proposal, granted an international mandate to form a transitional peace council (TPC), deploy a stabilisation force, and set a framework stretching until the end of 2027. In the midst of shaping this new transitional architecture, Blair’s anticipated role quickly emerged as a source of deep concern for many stakeholders.

Since the Trump administration began engaging in efforts to end the war, several plans have circulated. Yet the plan attributed to Blair appeared closest to Trump’s thinking and may have informed key elements of the vision he unveiled in late September. That alone reignited controversy: why would placing Blair in such a consequential position be viewed as a grave misstep?

Blair carries a heavy political legacy rooted in what many consider the most disastrous foreign policy decision of the 21st century: the 2003 invasion of Iraq, which he championed alongside then-US President George W Bush under the false pretext of weapons of mass destruction (as later confirmed by the United Kingdom’s Chilcot inquiry). The war devastated Iraq, fuelled sectarian conflict, opened the door to years of foreign intervention, and resulted in the deaths of hundreds of thousands of Iraqis. For many across the region and beyond, Blair became a symbol of unaccountable power and catastrophic decision-making.

Within the Palestinian and Arab context, Blair’s record is even more troubling. As the Quartet’s special envoy to the Middle East peace process from 2007 to 2015, he was widely accused of reinforcing Israeli policies, enabling the entrenchment of the Gaza blockade, and allowing Israel to evade its obligations under peace frameworks. Although the Quartet’s mandate was to support negotiations, foster economic development, and prepare institutions for eventual statehood, none of these goals meaningfully advanced during Blair’s tenure. Meanwhile, illegal Israeli settlement expansion accelerated, and the occupation deepened.

Most consequential was the Quartet’s decision, following the 2006 Palestinian legislative elections, to impose sweeping political and economic sanctions on the new Hamas-led government. These conditions, which required Hamas to recognise Israel and renounce armed resistance before lifting the blockade, effectively triggered Gaza’s long-term isolation. The decision dealt a severe blow to Palestinian political cohesion and helped entrench the division whose consequences are still felt today.

During Blair’s years in office, Gaza endured four devastating Israeli assaults, including the 2008-09 Operation Cast Lead, one of the bloodiest military campaigns in the Strip’s history during his mandate. Yet Blair achieved no political breakthrough. Instead, British media investigations revealed serious conflicts of interest, suggesting that the former prime minister used his Quartet role to facilitate business deals benefitting companies linked to him, earning millions of pounds despite his lack of diplomatic achievements. Multiple reports indicated that he was not fully dedicated to his envoy responsibilities, devoting significant time to his private consultancy work and lucrative speaking engagements.

In 2011, Blair also openly opposed Palestine’s bid for full UN membership, calling it a move that was “deeply confrontational” and reportedly lobbied the UK government to withhold support.

Years later, in 2017, he admitted that he and other world leaders were wrong to impose an immediate boycott on Hamas after its electoral victory – an admission that came only after Gaza had suffered the long-term consequences of that policy.

For these reasons, Palestinians, Arab states, and numerous donor countries perceived Blair’s anticipated role in the proposed board for peace with profound scepticism. Given his political record, clear alignment with Israeli positions, and unresolved allegations of profiteering, Blair is seen not as an impartial stabiliser but as a liability capable of undermining the fragile trust necessary for any transitional process.

Removing him is therefore a step in the right direction, yet not sufficient on its own. The real test lies in determining whether his private consulting firm and affiliated networks are also excluded, or whether his departure is merely symbolic. If Blair exits in name only, while his institutional influence persists behind the scenes, then the risks to the peace process remain substantial.

Source: Aljazeera

Leave a Reply