Berlin, Germany – The plaque that marks 77 William Street, the building in the German capital where a meeting that forever shaped Africa’s fate took place, is different.

This one made of steel, which is curved awkwardly in front of a tree and bears an old map of Africa in vibrant red and blue colors, is different from those next to it, which are official square plaques with dark colors that depict Nazi Germany’s Nazi history. That’s because it’s relatively new and was created by the Afrika Forum, an organization that didn’t exist until Berlin, three years ago.

The obscure loneliness of the Africa plaque reveals how Germany remembers or forgets its colonial past in a nation that is renowned for its thorough and prolific remembrance of Nazi crimes committed during the 20th century.

On a winter afternoon, a few tourists troop past without as much as a glance, heading towards the remnants of the Berlin Wall, about 200 metres (650 feet) away, and a memorial for Jews murdered in the Holocaust. The former palace’s residence now includes an apartment complex and a few restaurants and cafes on the ground floor. Even the people working nearby do not know how important this location is in African history – “Keine Ahnung]No idea]”, one waitress, replied, when asked.

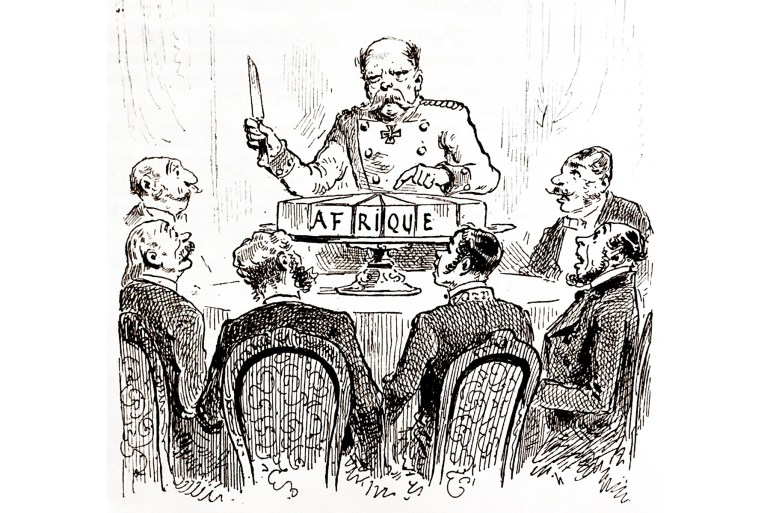

The carving up of Africa and the colonization game were finalized exactly 140 years ago when European leaders gathered at this location today. They’d been haggling on and off for about three months, from November 15, 1884, until February 26, 1885, arguing about who owned which territories on the continent. The meeting, dubbed the Berlin or the Congo Conference, would continue to ratchet up Africa’s occupation, which still resonates today.

Here in Germany though, that history is largely a black hole.

“I don’t remember that we talked about colonialism a lot”, Berlin resident Sanga Lenz, 34, told Al Jazeera. Growing up, her school’s history curriculum centred around the Holocaust, the second world war, and the Cold War. Lenz was introduced to German imperialism by a history teacher who had previously taken the class to a slavery exhibition. But it wasn’t until 2020 when she realized how deeply connected she was to the past when she discovered a photo of an old male relative stationed in the colonies.

He was constructing these train tracks there while stationed in German East Africa. I was like, wait a minute. Of course, this happened, but nobody ever talked about it. Growing up in Germany people talk about how some relatives were Nazis, but no one talks about this history”, Lenz said incredulously.

One of the few city tour guides who tries to point out the Africa plaque is Johnny Whitlam, who is one of the few in the city. “People are usually happy to find out about this, even if that’s not what they came to see”, he said.

Still, he admits, interest in the monument is minimal, something he believes largely reflects that authorities have not prioritised the issue.

“I’d say there’s definitely not enough being done in terms of the awareness of this history”, Whitlam said.

For Nadja Ofuatey-Alazard, an activist and co-director of Each One Teach One (EOTO) which advocates for the interests of Africans and Afro-Germans, Germany has chosen to focus on its most recent dark history but has failed to examine its brutal precursor.

“Germany is slow to come to the realisation that it was a colonial power”, Ofuatey-Alazard said. Although the nation’s main historical focus is on National Socialist history, Germany has to this day not yet taken action in accordance with its historical obligation. It needs to come into the mainstream. It has to wind up in schools and universities”.

The European summit that shaped Africa

In the late 1800s, European powers became embroiled in a mad “scramble for Africa”, as that period is now known. Their goal was to retake control of everything from palm oil to rubber that they had been purchasing on the continent.

Germany, the Ubited Kingdom, Portugal and France each tried to outdo the other, forcing local African leaders to sign exclusive “protection treaties” that meant they’d lose their sovereignty. At times, colonial officers bought vast expanses of African territory, or in other instances, scouts simply staked a country’s flag in an African nation to claim it.

Otto von Bismarck, the then-German Chancellor, was in charge of calling his rival European counterparts to the Berlin Conference to prevent a war in Europe as nations began toss heads over the colonies from their homes at the time.

Due to the expense of establishing and maintaining colonial governments and the stringent diplomatic arrangements required, Bismarck initially seemed only passably interested in the fight for Africa, according to historians. A growing movement of German pro-colonial writers and lobbyists who published articles to highlight the potential for the German Empire’s sphere of influence pressured him, though. Germany was rapidly industrialising, and free labour and resources from the colonies was an opportunity Bismarck later came to appreciate. Bismarck and French government officials both agreed that there must be some order, according to documents containing their correspondence in the months leading up to the meeting’s call.

Fourteen countries took part in the Berlin Conference, with 19 delegates in total, including from the United States. There were no African representatives, not even from the Europe-recognised nations of Ethiopia, Liberia or Zanzibar.

By the end of the conference, a General Act spelling out the rules of “effective occupation” had emerged: Countries were to no longer merely stake flags and declare territories as their own, for example, but had to actually enforce their authority on the existing African nations. The Congo and Niger Basins were also free of charge for navigation, and Belgium’s King Leopold’s claim to the area, which would later be called the Congo Free State, was acknowledged.

Germany claimed four major areas: German East Africa, Kamerun, Togoland, and German Southwest Africa.

“Greed and hubris,”

Some researchers don’t completely agree that the Berlin Conference essentially sealed the fate of Africa, as is widely believed. According to Jack Paine, a researcher at Emory University, African states were already forming prior to the conference and that many nations’ borders wouldn’t become legally binding until many years later. However, the conference likely went on to prompt a more frenzied rush to occupy colonies, he added.

According to Paine, “the Berlin Conference was a clear example of European hubris and greed.” “In many ways, it served to legitimise]among Europeans] the ongoing process of claiming African territory, although even this interpretation warrants caution. Perhaps a large gathering of influential politicians who were present at the conference helped to boost efforts to rule the entire area in comparison to a different world where the conference did not take place.

Indeed, within five years of the conference, the percentage of colonised parts of Africa went from 20 to 90 percent. The German Schutztruppe, or colonial guard, was particularly brutal in the colonies. In present-day Namibia, German troops massacred thousands from the revolting Herero and Nama people for their resistance, and then put them in concentration camps.

“They rented out the women to German companies and German settlers”, activist Sima Luipert, whose great-grandmother was “rented” and who is now part of a group of Herero and Nama leaders pressing Germany for reparations, told Al Jazeera.

Because Germany lost World War I, and thus all its African possessions by 1919, there’s a lingering sense in the country that it didn’t have much stake in the game, and that other European powers, such as Belgium, did much worse. But that thinking is flawed, activists point out.

“European leaders love to point to each other and say, ‘ No, they did worse than us, ‘” Ofuatey-Alazard of EOTO said. They all committed terrible crimes, the truth is. Germany needs to acknowledge more history.

Hoping to push for better acknowledgement of that history, Ofuatey-Alazard has led the organisation of a series of “Decolonisation” Conferences since 2020, a project partly sponsored by the state. Delegates from African nations gathered for the first conference to talk about the effects of colonization on Africa today.

“I decided to come up with a format that was a counter-conference”, she said. “Since there had been 19 delegates at the historic]Berlin] Conference representing 14 nations back then, I mirrored that and invited 19 women of African descent, because obviously, historically it had been 19 men”.

In the most recent conference in November, another set of 19 delegates, this time all people of African descent, came up with a 10-point list of demands for European countries: Pay reparations, abolish tenuous visa regimes, and protect human rights at a time when , Europe is veering dangerously to the right, the document read. However, the European Union has not yet responded to those requests, the activist said.

Traces of the past in the present

Justice Lufuma Mvemba, a girl from Germany who raised her, claimed that she had a hard time juggling what was being said to her in class and her conversations with peers and the reality of her family.

In the midst of a period of unrest in the 1990s, her family fled the Democratic Republic of the Congo. The colonial powers’ intervention in its local politics severely divided the nation, which is still at war today.  , At home, her father’s fear of violence was so enormous that he wouldn’t let them play with toy guns.

But in Germany, people would refer to colonial history as being “not that relevant”, and history classes were devoid of any critical thinking on imperialism. “I was confused”, said Mvemba, 33, who found it hard not to notice how Africa’s resources were being dominated by foreign powers.

Mvemba founded the Decolonial City Tour in order to provide a more accurate view of the situation, showing both residents and visitors parts of Berlin that still have colonial and controversial histories.  , It’s a unique concept in the city.

A typical tour takes visitors down to the African Quarters, in the city’s Mitte district. Carl Hagenbeck, an animal lover, created the tranquil residential area, which is lined with pastel-colored modernist apartment blocks and houses a human zoo where “exotic” people from German colonies would be displayed. It is why some of the streets here are named after former colonies: Togo Street, or Windhoek Street for example. Hagenbeck’s death from a snakebite and the outbreak of World War I, however, scuttled those plans.

At Manga-Bell Square, tourists learn that the public space only got its name in 2022. Initially, it was named after Gustav Nachtigal, the German commissioner for Africa who was instrumental in taking control of Cameroon, Togo and Namibia. After years of controversy, the Berlin city council finally settled on the name Rudolf Manga-Bell, the Cameroonian prince who was put to death by colonial Germany in 1914 on treason charges. He dared to question the Duala’s arbitrary displacement of his people.

As the group walks around, guides often throw in fun facts. One fact that many people are astonished is that the well-known German grocery store, Edeka, was originally abbreviated as (E) inkaufsgenossenschaft (de) r (K) olonialwarenhaendler, or Cooperative of Colonial Grocers.

Mvemba reported that her mostly German clientele frequently approves her. “It’s always interesting to see people’s reactions to that”, she said. “People are always like, ‘ Wow, I had no idea’, and they do appreciate that history”.

Some, she said, struggle to see the less appealing side of Germany, criticizing Mvemba or quietly slipping away as the group circles a corner. “It’s a very small percentage, but it’s there. And sometimes we get nasty comments on social media, too”.

This is a major factor in why activists believe that Germany needs to make more money to preserve its past and make appropriate reparations for its former colonies. Ofuatey-Alazard says the country’s future of remembrance is uncertain, despite Olaf Scholz’s government’s departure from the Social Democratic Party’s agenda.

In last week’s general elections, the conservative Christian Democrats Union (CDU) party won, but the far-right Alternative for Germany (AfD) party , recorded strong gains too, becoming the strongest opposition in parliament. That’s a threat, the activist said.

“Even though]the far-right] might not wind up in government as the conservatives have promised, the problem is that they are sort of driving the others, and pushing the others, and so that is of concern”, Ofuatey-Alazard said. “And definitely, the AfD is completely against any decolonial or memory culture. They are completely denialist about the past, so they are completely ignorant. We aren’t yet sure how that will affect our work. We are obviously very worried”.

Source: Aljazeera

Leave a Reply