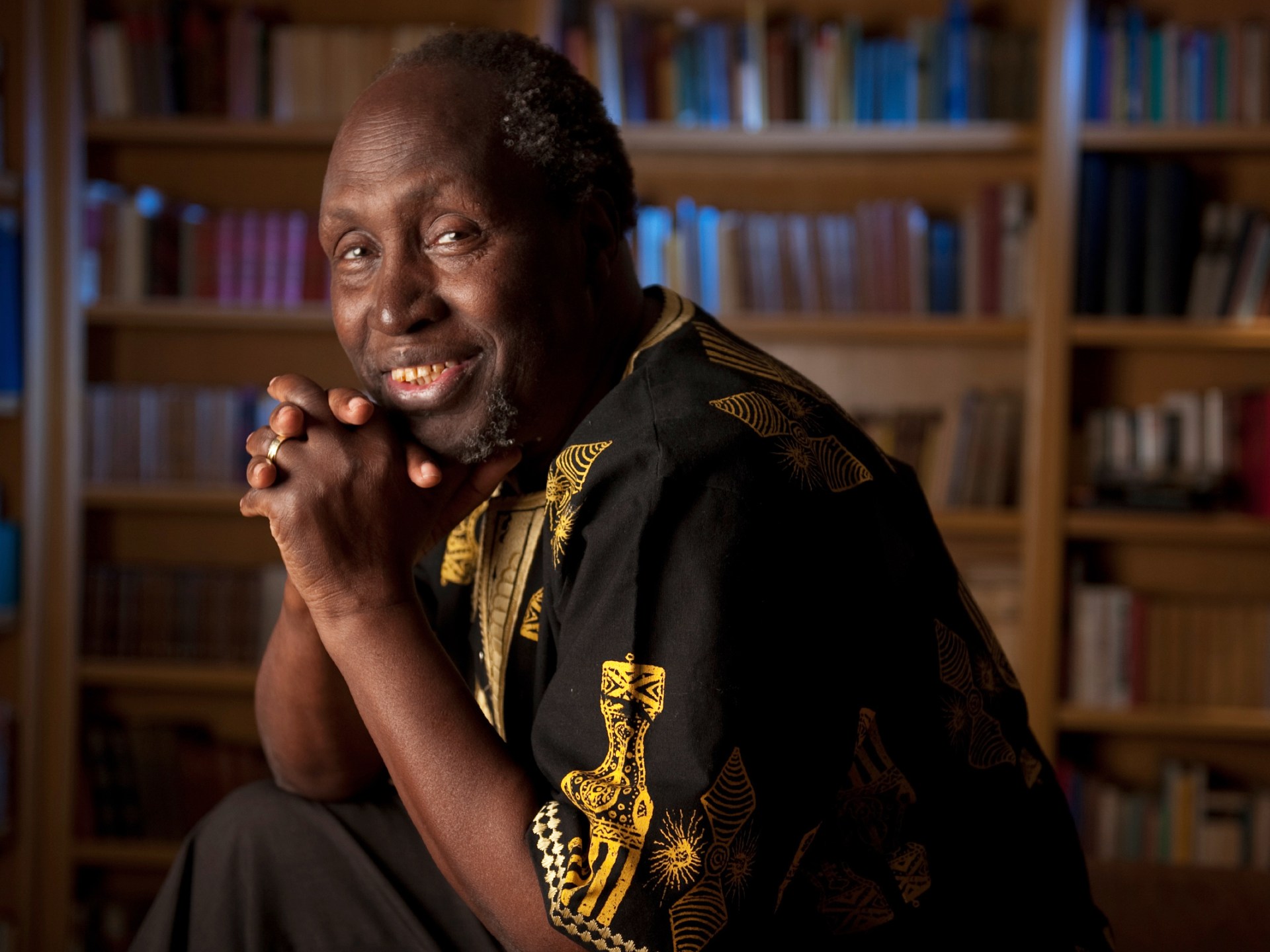

Ngugi wa Thiong’o was a dancer. He adored it more than anything else, even more so than writing. Ngugi would get up and start dancing at the sound of music just as his body slowed as his body slowed as his body slowed as his body slowed down. His feet felt like words did, and he felt the rhythm of the page.

I’ll always be able to recall Ngugi dancing because of it. He passed away on May 28 at the age of 87, leaving behind a deeply innovative literary legacy and piercingly original criticism that joyfully calls on writers, activists, teachers, and people to work harder in opposition to colonial foundations that sustain all of our societies. He forepushed me to travel much further up the river to the Kakuma refugee camp, where he would always attribute his greatest gift, writing, being able to freely express his thoughts and opinions “from the heart.”

By the time I first met him in 2005, Ngugi had long been a cherished Nobel laureate and a founding member of the African literary canon. After getting to know him, it quickly became clear that his writing and teaching were inseparably linked to both of his political commitments and long service as one of Africa’s most powerful public figures.

Ngugi was a child, young man, and adult victimized by successive and deeply intertwined systems of criminalized rule, despite his cheerfulness and unwavering smile and laugh and unwavering smile.

His deaf brother’s murder, which the British killed because he refused to obey soldiers’ orders to stop at a checkpoint, and the Mau Mau revolt that divided his other brothers on opposing sides of the colonial order during the final ten years of British rule, gave him the fundamental reality that violence and divisiveness were the twin engines of permanent coloniality even after independence formally severed the connection to the metropole.

Nothing could stifle Ngugi’s enraged rage more than bringing up the transition from British to Kenyan rule and the fact that colonialism didn’t abandon the British but instead resisted the British’s attempts to reinvigorate itself with Kenya’s new, Kenyan rulers.

Ngugi, a writer and playwright, also developed a militant bent on reuniting the complex African identities that the “cultural bomb” of British rule had “annihilated” over the previous seven decades.

He was quickly recognized as a voice who “speaks for the Continent” after his first play, The Black Hermit, was first performed in Kampala in 1962. His first novel, Weep Not Child, and the first East African author’s work in English, was published two years later.

Ngugi decided to start writing in his native Gikuyu as he gained notoriety.

The (re)adoption of his native tongue significantly altered the course of both his career and his life because the ability of his lucid analysis of postcolonial rule to reach his fellow citizens in their own language (as opposed to English or Swahili), was too much for Kenya’s new rulers to tolerate. In 1977, he was imprisoned for a year without being tried.

Ngugi realized that neocolonialism was the primary mechanism of postcolonial rule when he began writing in Gikuyu, and even more so when he was imprisoned. Anti- and post-colonial activists didn’t use the standard “neocolonialism” to describe the continued dominance of former colonial rulers through other means after formal independence, but rather the willing adoption of colonial technologies and discourses of rule by newly independent leaders, many of whom, like Jomo Kenyatta, Ngugi liked to point out, themselves endured imprisonment and torture under British rule.

Thus, true decolonization could only occur when people’s minds were freed from foreign control, which required, perhaps most importantly, the right to write in one’s own language.

Ngugi’s theory of neocolonialism, which he would frequently credit with Kwame Nkrumah’s writings and other African anti-colonial intellectuals-turned-political leaders, was almost a generation ahead of the now-distant “decolonial” and “Indigenous” turns in the academy and progressive cultural production.

Indeed, Ngugi is regarded as the first generation of postcolonial criticism along with Edward Said, Homi Bhabha, and Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak. However, he and Said shared a similar all-encompassing focus on language, even though Said wrote his prose primarily in English rather than Arabic, which he and Said frequently discussed as he frequently exchanged barbs and was a close friend of Polish-British author Joseph Conrad.

Colonianism was still a very real, visceral, and violently lived reality for Said and Ngugi thanks to settler colonialism, which had not yet passed, and which was ultimately annihilated by successive governments.

Ngugi and Said shared a common childhood experience under British rule, which he saw as a result. According to him, disrupting that authority and putting an end to the silence could only be done through language, as he stated in his afterword to a recently published collection of Egyptian prison writings from 2011’s anthology of colonial writings.

For Said, the Arabic and English worlds he’d known as being young had a “primal instability,” which he could fully unwind while living in Palestine, which he frequently visited throughout his life. Even as Gikuyu taught him to “imagine another world, a flight to freedom, like a bird you see from the]prison window,” Ngugi was unable to make a final trip home in his final years.

He would never tire of urging students and younger colleagues in Orange County, California, to “write dangerously” and to use language to oppose any oppressive order they found themselves in from his home. If you could write fearlessly, the bird would always take flight, he would say.

Source: Aljazeera

Leave a Reply