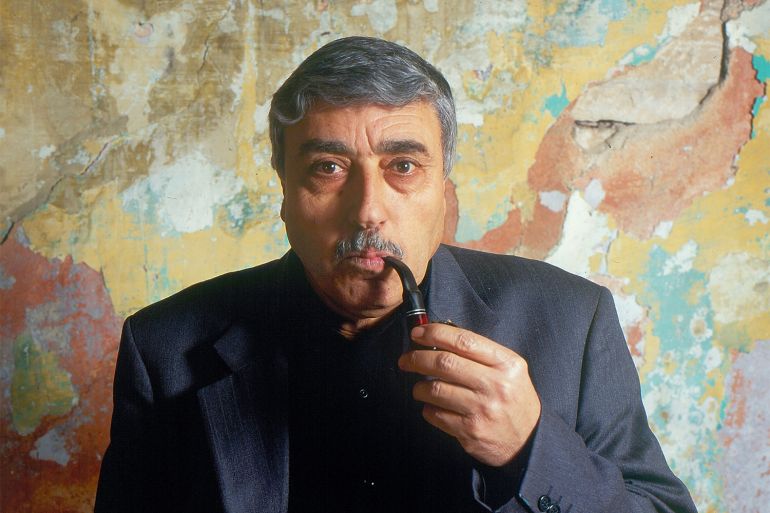

In the quiet of his Ramallah studio in the occupied West Bank, Palestinian artist Nabil Anani works diligently on artworks deeply rooted in a movement he helped create during the political tumult of the late 1980s.

Cofounded in 1987 by Anani and fellow artists Sliman Mansour, Vera Tamari and Tayseer Barakat, the New Visions art movement focused on using local natural materials while eschewing Israeli supplies as a form of cultural resistance. The movement prioritised self-sufficiency at a time of deep political upheaval across occupied Palestine.

Recommended Stories

list of 3 itemsend of list

“[New Visions] emerged as a response to the conditions of the Intifada,” Anani said. “Ideas like boycott and self-reliance inspired a shift in our artistic practice at the time.”

Each of the founding members chose to work with a specific material, developing new artistic styles that fit the spirit of the time. The idea caught on, and many exhibitions followed locally, regionally and internationally.

Nearly four decades later, the principles of New Visions – self-sufficiency, resistance and creation despite scarcity – continue to shape a new generation of Palestinian artists for whom making art is both an expression and an act of survival.

Anani, now 82, and the other founding members are helping keep the movement’s legacy alive.

Why ‘New Visions’?

“We called it New Visions because, at its core, the movement embraced experimentation, especially through the use of local materials,” Anani said, noting how he had discovered the richness of sheepskins, their textures and tones and began integrating them into his art in evocative ways.

In 2002, Tamari, now 80, started planting ceramic olive trees for every real one an Israeli settler burned down to form a sculptural installation called Tale of a Tree. Later, she layered watercolours over ceramic pieces, mediums that usually do not mix, defying the usual limits of each material, and melded in elements of family photos, local landscapes and politics.

Sixty-six-year-old Barakat, meanwhile, created his own pigments and then began burning forms into wood, transforming surface damage into a visual language.

“Other artists began to embrace earth, leather, natural dyes – even the brokenness of materials as part of the story,” Mansour, 78, said, adding that he had personally reached a kind of “dead end” with his work before the New Visions movement emerged, spending years creating works centred around national symbols and identity that had started to feel repetitive.

“This was different. I remember being anxious at first, worried about the cracks in the clay I was using,” he said, referring to his use of mud. “But, in time, I saw the symbolism in those cracks. They carried something honest and powerful.”

In 2006, the group helped create the International Academy of Art Palestine in Ramallah, which was open for 10 years before being integrated into Birzeit University as the Faculty of Art, Music and Design. The academy’s main goal was to help artists transition from older ways of thinking to more contemporary approaches, particularly by using local and diverse materials.

“A new generation emerged from this, raised on these ideas, and went on to hold numerous exhibitions, both locally and internationally, all influenced by the New Visions movement,” Anani said.

A legacy maintained but tested

The work of Lara Salous, a 36-year-old Palestinian artist and designer based in Ramallah, echoes the founding principles of the movement.

“I am inspired by [the movement’s] collective mission. My insistence on using local materials comes from my belief that we must liberate and decolonise our economy.”

“We need to rely on our natural resources and production, go back to the land, boycott Israeli products and support our local industries,” Salous said.

Through Woolwoman, her social enterprise, Salous works with local materials and a community of shepherds, wool weavers and carpenters to create contemporary furniture, like wool and loom chairs, inspired by ancient Bedouin techniques.

But challenges like the increasing number of roadblocks and escalating settler violence against Palestinian Bedouin communities, who rely on sheep grazing as a basic source of income, have made working and living as an artist in the West Bank increasingly difficult.

“I collaborate with shepherds and women who spin wool in al-Auja and Masafer Yatta,” said Salous, referring to two rural West Bank areas facing intense pressure from occupation and settlement expansion.

“These communities face daily confrontations with Israeli settlers who often target their sheep, prevent grazing, cut off water sources like the al-Auja Spring, demolish wells and even steal livestock,” she added.

In July, the Reuters news agency reported an incident in the West Bank’s Jordan Valley, where settlers killed 117 sheep and stole hundreds of others in an overnight attack on one such community.

Such danger leaves Palestinian women who depend on Woolwoman for their livelihoods vulnerable. Several female weavers working with Salous and supporting her enterprise have become their families’ sole breadwinners, especially after their spouses lost jobs due to Israeli work permit bans following the Hamas-led attacks on southern Israel on October 7, 2023, and the start of the Gaza war.

Visiting the communities where these wool suppliers live has become nearly impossible for Salous, who fears attacks by Israeli settlers.

Meanwhile, her collaborators must often prioritise their own safety and the protection of their villages, which disrupts their ability to produce wool to sustain their livelihoods.

As a result, the designer has faced delays and supply chain issues, making completing and selling her works increasingly difficult.

Anani faces similar challenges in procuring hides.

“Even in cities like Ramallah or Bethlehem, where the situation might be slightly more stable, there are serious difficulties, especially in accessing materials and moving around,” he said.

“I work with sheepskin, but getting it from Hebron is extremely difficult due to roadblocks and movement restrictions.”

Creating vs surviving

In Gaza, Hussein al-Jerjawi, an 18-year-old artist from the Remal neighbourhood of Gaza City, is also inspired by the New Visions movement’s legacy and meaning, noting that Mansour’s “style in expressing the [conditions of the occupation]” has inspired him.

Due to a lack of materials like canvases, which are scarce and expensive, al-Jerjawi has repurposed flour bags distributed by the United Nations agency for Palestinian refugees (UNRWA) as canvases for creating his artwork, using wall paint or simple pens and pencils to create portraits of the world around him.

In July, however, the artist said flour bags were no longer available due to Israel’s blockade of food and aid into the Gaza Strip.

“There are no flour bags in Gaza, but I’m still considering buying empty bags to complete my drawings,” he said.

Gaza-born artist Hazem Harb, who now lives in Dubai, also credits the New Visions movement as a constant source of inspiration throughout his decades-long career.

“The New Visions movement encourages artists to push boundaries and challenge conventional forms, and I strive to embody this spirit in my work,” he said while noting that it has been challenging to source the materials from Gaza that he needs for his work.

“The ongoing occupation often disrupts supply chains, making it difficult to obtain the necessary materials for my work. I often relied on local resources and found objects, creatively repurposing materials to convey my message.”

Anani, who said the conditions in Gaza make it nearly impossible to access local material, added that many artists are struggling but still strive to make art with whatever they can.

“I believe artists [in Gaza] are using whatever’s available – burned objects, sand, basic things from their environment,” Anani said.

“Still, they are continuing to create in simple ways that reflect this harsh moment.”

Source: Aljazeera

Leave a Reply