I once came across a Dylan Thomas poem while I was in county lockup that I didn’t understand completely. “Rague, rage against the dying of the light” was the phrase used in the passage.

I enjoyed its urgency and rhythm. However, I was unsure of what it meant to rage inside the beast’s belly.

I’d be able to learn something soon.

When education is insufficient

While incarcerated in the Hudson County Correctional Center in Kearny, New Jersey, I began studying law. I owned and operated a successful phone and laptop sales business at the age of 25, and I was street smart, well-traveled, well-read, and educated. And yet, I was unable to follow the legal language. Everyone else spoke fluently, which sounded strange. I emailed my attorneys, but I didn’t press. I’m new. I had faith in them.

I still have to wonder about it because of it. If I had known what I now know, I would have pressed on to use various legal tactics to defend my case. I don’t think I would have received two life sentences in a row, which would have been 150 years in prison, if I had done that.

The system wants you to sit down, shut up, and follow through, you see. However, every error is a noose-like garment around your neck. The court’s starting point is “sound trial strategy,” which means they think the defense lawyer did their job well from the beginning, if you try to appeal.

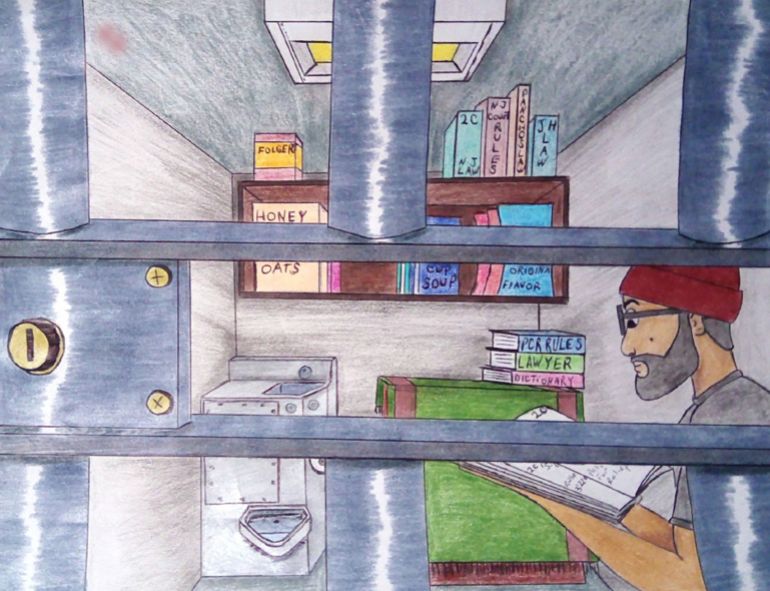

No legal counsel, just strategy, enters the law library.

An older prisoner told me that your job is to stay out of trouble, live, and fight for your life when I arrived at Trenton’s NJSP in 2005. No one has saved us. Go to the law library to learn.

Inmate Legal Association (ILA), a prisoner-run paralegal organization, I joined in. I received training, and I obtained a paralegal license.

Soon after joining the ILA, I launched my own legal battle and began assisting others. A procedural motion, which assisted a fellow inmate in returning to court, was my first victory. In my mind, that thought is still a trophy. The struggle was worth it when you assisted someone else.

I wanted to contest my conviction in the federal habeas court, which was a different story. My petition was thrown out. But I made an appeal. I made my research reliable. I submitted. And I prevailed. The petition was later rejected because the outcome wasn’t persuasive. However, we can resist the short-lived victory.

Hidden resistance behind bars

Pro se litigant lives the life of a person who represents themselves in court; pro se means “for oneself” in Latin. It’s more of a necessity than a choice to represent you as your own legal representative. For my trial and initial appeals, the state assigned a second attorney, and I retained my own attorney. I was by myself right after that. I was unable to afford legal counsel. I’m not the only one, either.

Every year, tens of thousands of prisoners submit pro se motions. According to US court data from 2000 to 2019, 91 percent of inmate legal challenges were brought in secret.

This is not a new thing. According to a report from the Bureau of Justice Statistics from the middle of the 1990s, 93 percent of state prisoners’ initial petitions for habeas corpus were pro se.

These figures confirm what we see inside: legal representation ends after the first appeal, and after that, we are alone, with no training, limited resources, and significant obstacles.

Voices from the legal underground

Take Puerto Rican Martin Robles, 52, who has spent nearly 30 years in jail. Martin took over his appeals once he had no longer a lawyer in place. He said, “The courts don’t uphold their own laws.” They don’t hold the prosecution accountable like they do with us. We are timed (and appeals are denied) because we are an hour late. But prosecutors? They have unlimitable leeway.

The courts are not interested in how difficult it is for prisoners to communicate with paralegals or conduct case-study in order to write legal briefs. The law library’s ability to do all of this is restricted. Although the passes are limited, and we sometimes wait weeks before entering the library, we must request a visit pass during our housing unit’s weekly rotation. Courts frequently impose deadlines on prisoners that are also impossible to meet, but they also fail to give any latitude regarding prison restrictions. For instance, a friend received a month to file a legal brief, but because he had a cast on his arm, which was viewed as a potential weapon, he was not permitted to use the prison library at the time. However, he was unable to use the computers or consult legal reference books to type his brief without access to the library. He wrote to the judge about his plight, but he was not given an extension after the deadline expired.

Martin has transformed his fury into a positive outcome. He stated, “I’m introducing my first law school at NJSP in Spanish.”

It is voluntary, they say. For the people, I’m doing it. They’re getting too much of being taken advantage of.

When protection is in vain.

Kashif Hassan, 39, used private attorneys to enter the system after earning a master’s degree. He claimed that he “thought I was good” when I threw money at lawyers. However, I was manipulated and railroaded. I didn’t start the fight early enough.

Kashif eventually readjusted his future and became a master of it. He claimed that his first success was a bail motion in the county jail [jail].

No one else will fight if you don’t fight. If you are aware of your actions, pro se litigation will work. However, we are treated like amateurs by courts. “We don’t count,” as we might say.

A lawyer who avoided preparing a defense

Tommy Koskovich, 47, was detained in high school. He recalls that “my attorney mocked me.” “Said he didn’t prepare a defense because the Public Defender’s Office didn’t pay him enough. He said, “I didn’t prepare a defense for you,” when I declined the plea deal.

Tommy has since lost all of his previous appeals, but he is now seeking clemency and a motion to overturn his sentence. Through New Jersey’s new Clemency Initiative, he has also applied for the latter.

Tommy has discovered how to identify legal issues throughout the process. He claimed that “some courts only take your issue seriously after you file pro se.” An inmate raised the issue himself in State v. Comer, which is how it happened.

After committing numerous armed robberies with two others in 2000, James Comer, age 17, was found guilty of a felony murder and other crimes. He served an 85-year prison sentence until his death. He was sent to the New Jersey Supreme Court after fighting with his attorneys, which was likely to have put him to death. After serving for 25 years, he was released in October.

The system is built for conviction, not justice, as many of the people behind the wall are aware of. You are on your own when your initial appeals are over.

You are held accountable for your errors. Every error is used to make the door more secure.

A moral battle is also involved in the legal battle.

We fight, though. Under stuttering lights, we write in shattered chairs. We teach legal terminology, how to navigate case law, and how to decipher legal terminology.

In terms of my case, I’m working on both an alternative motion to renounce my sentence and a DNA test to prove my innocence. I’m waiting on the outcome of several cases that are pending in the New Jersey Supreme Court.

because we don’t keep silent.

We don’t enter that happy hour quietly.

We protest unfair verdicts, disparaging courts, and a system that promises to end our lives.

Even when no one is watching, we rage.

Even if no one is convinced.

Even when there are few victories.

After all, there is hope in motion in rage.

Source: Aljazeera

Leave a Reply