Joe Trejo Lopez feared that the immigration agent had separated him from Josue, allowing the officer to pose more questions during a check-in in New York City in March.

Jose and Josue, 20 and 19 years old at the time, had been to dozens of Immigration and Customs Enforcement check-ins in the nearly 10 years since they fled El Salvador as children with their mother. The appointments frequently required missing school and final exams and extended hours of the day. Joe knew he had to fulfill his immigration obligations, maintain good conduct, and keep a clean arrest record despite the fact that he had to tell his classmates and teachers where he was going.

“You have to follow the law, because when you follow the law things go well, right”? Joe stated.

Jose audibly resonant that day as handcuffs swayed. The officer told him not to make a scene. A different officer handcuffed him as he turned and observed his older brother restrained.

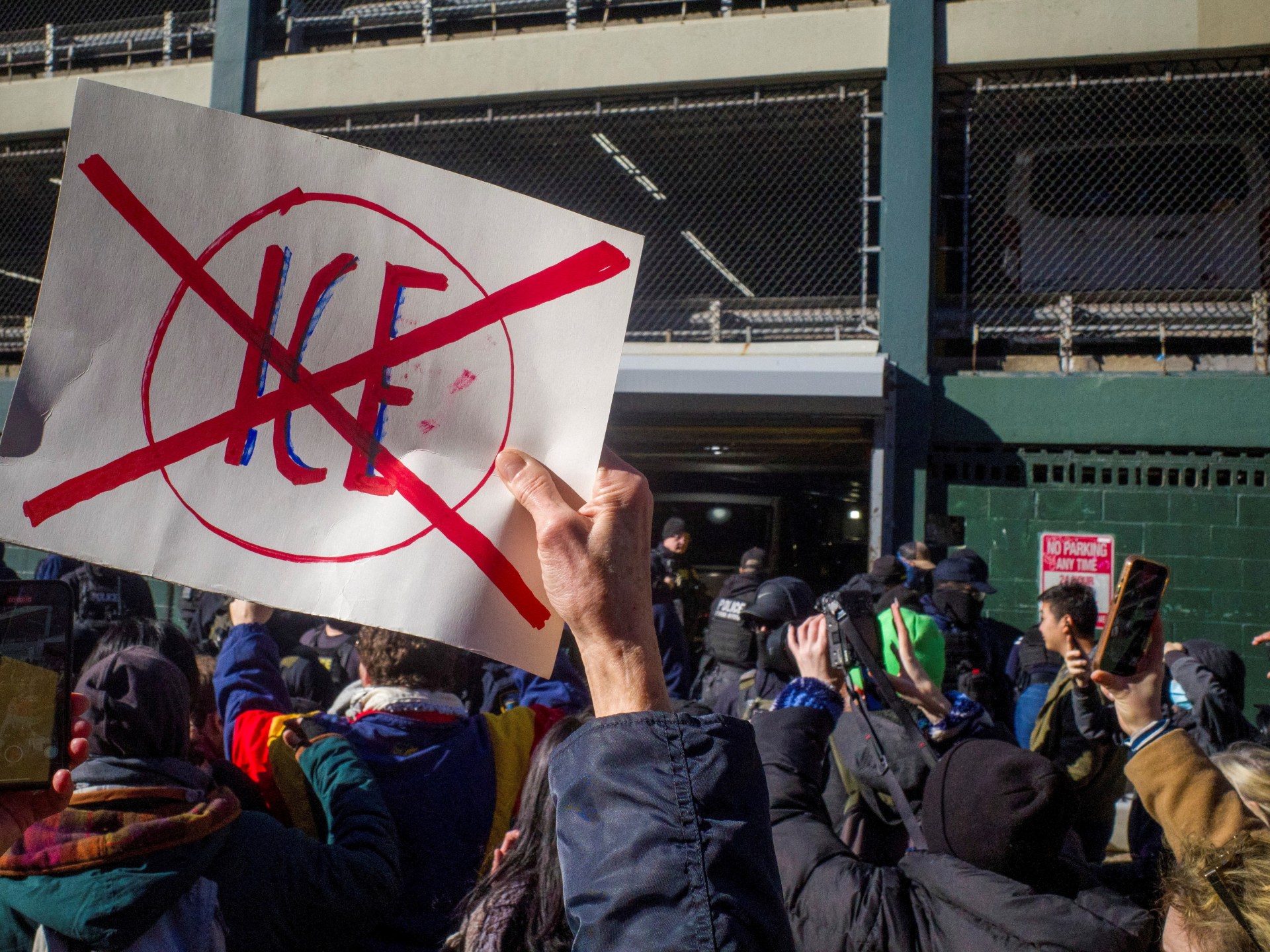

About two months into President Donald Trump’s second administration, when the brothers were arriving at ICE’s field office for their 8am appointment, rumors were circulating that immigration agents were detaining people during routine immigration check-ins. These appointments are typically for people with pending immigration cases who aren’t considered threats to the public.

One of Trump’s campaign promises for 2024 was to keep people at check-ins, which included putting people to sleep. However, the approach contradicted Trump’s and his administration’s assurances that immigration agents would always put “the worst of the worst” first.

“I’m talking about, in particular, starting with the criminals. On August 22, 2024, Trump  declared that these are some of the worst people in the world.

Norah O’Donnell, a CBS News correspondent, inquired about Trump’s October 31 statement that he had promised to “deport the worst of the worst, violent criminals.” Trump answered:  , “That’s what we’re doing”.

Jose and Josue have neither been found guilty of a crime. As of November, a , a , record number of detainees were in ICE detention, which is true of 73 percent of the more than 65, 000 immigrants. Nearly half of all immigrants in ICE detention have neither a criminal conviction nor pending criminal charges. According to the Cato Institute, a libertarian think tank, 5% of immigrants who have had criminal convictions have been found guilty of violent crimes, including murder and rape.

Despite what Trump said, violent criminals were not subject to widespread arrests during his administration’s mass deportation campaign.

In March, the Department of Homeland Security sent nearly 250 Venezuelan men to a maximum security prison in El Salvador. Only 32 of the men had US criminal convictions, the majority of which were for nonviolent offenses like traffic violations or retail theft, according to a ProPublica  investigation later.

According to a Chicago Tribune analysis, immigration officers detained 1,900 people during the first half of a months-long immigration crackdown known as “Operation Midway Blitz.” Two-thirds of those detained had no criminal convictions or pending charges.

When PolitiFact asked the White House whether its detention strategy was in line with what Trump and officials have said publicly, spokesperson Abigail Jackson said: “The Trump Administration’s top immigration enforcement priority is arresting and removing the dangerous violent, illegal criminal aliens that Joe Biden let flood across our Southern Border – of which there are many. Criminal illegal aliens who have been raped, pedophiled, and murdered have recently been detained by the ICE. However, if someone uses self-deportation opportunities and is illegally present in the country and thus violates US laws, they may be deported.

Jose and Josue were applying for legal status. They had appeared before immigration judges and ICE officers for years without hiding.

Jose and Josue were taken to El Salvador in May, where their rest of their family had already fled.

“We followed the law and we were punished”, Jose said.

The brothers’ search for legal residency

Jose and Josue, who are 11 and 10 years old, and their mother Alma Lopez Diaz, both fled El Salvador and were threatened with gang violence in the US in summer 2016.

US officials stopped the family at the southern border and released them into the US while they sought asylum. In Georgia, the family moved in with the boys’ aunt.

The brothers continued to study English by using language-learning apps, reading books, and correcting themselves when their classmates teased them.

By 2020, judges had denied the family’s asylum case and appeals because gang extortion is not generally considered a reason for asylum, said Ala Amoachi, who became the brothers ‘ immigration lawyer in 2024. A deportation order had been issued for Joe and Josue.

When people appeal deportation orders, the appeal process is halted. Jose and Josue were appealing until 2020, when their appeals ran out, but they continued to appear at ICE check-ins. Because they had no criminal records at the time, Amoachi claimed, the government probably didn’t deport them because of “family unity” and the fact that their younger brother is disabled and a citizen of the US.”

According to their attorney, which they started in 2024, the brothers had a viable path to legal status by the time they were detained in 2025.

We contacted DHS to ask why the brothers were detained and deported while they had a pending immigration case and received no reply.

Trump has significantly slowed immigration legal pathways during his second term. He ended a Biden-era program in January that allowed people to schedule border immigration appointments and apply for asylum in the US. Under Trump, the Department of Homeland Security has stripped , hundreds of thousands of people of , temporary legal protections that let them live and work in the US.

Jose made an effort to realize what he had hoped would become an American dream, but his immigration status prevented him from getting a job and buying a car.

The brothers relocated to Long Island, New York, where their mother’s long-distance partner resided in 2024.

Amoachi initiated a process for them to apply for , Special Immigrant Juveniles Status, a protection for young immigrants who were abused, abandoned or neglected by a parent. According to court documents, the brothers’ father had abandoned them. The status allows immigrants to eventually apply for permanent residency once they are approved. The brothers ‘ previous lawyer in Georgia had failed to tell them this status was an option, Amoachi said.

Immigration recipients of Special Immigrant Juvenile Status were spared deportation under the Biden administration. The Trump administration began detaining people with Special Immigrant Juveniles status in June and ended their detention protection program. Immigrant advocacy groups are , suing , the government over the changes.

a sudden, unexpected result

Jose had a short-lived dream to start fresh in New York.

At the March 14 appointment, an ICE officer asked whether the brothers were contesting their removal order, and when Jose handed over their paperwork, the officer said, “‘ This doesn’t work'”, Jose recounted.

The brothers were in handcuffs within a few seconds.

Although there is no information on how many people have been detained and separated from their families during the required ICE check-ins, there are numerous stories on social media and in news stories about immigrants who have been detained and separated from their families. Lawyers have warned clients about the tactic. Numerous immigrant people in San Diego are suing the government for their detention during check-ins.

Before Trump’s second term, Amoachi, a 15-year veteran immigration lawyer, said she had never seen a case like Jose and Josue, a young men without criminal convictions or gang affiliation and pending applications, end in detention.

About a week after the brothers were detained, Trump’s border czar Tom Homan said the administration was prioritising criminals.

Homan  stated on March 23 that “we’re going to keep pursuing the worst of the worst,” which we’ve been doing since Day One, and deporting from the US.

Leaving behind everything

Detention was the first leg in a two-month journey which would take the brothers back to El Salvador.

Immigration officers shackled the brothers and transported them to a detention facility in Buffalo, New York, within hours.

Jose and a detained pastor co-hosted weekly church services while he was in custody. Josue took a job in the kitchen – cleaning dishes and helping serve food – earning $1 a day. He paid for the ramen, a delicacy in detention, with the money to call his mother or purchase it. Additionally, Joe served as an immigration officer’s unofficial translator and taught English to other detainees.

On March 26, a New York family court judge ruled that Jose and Josue had been abandoned by their father and it was not in their best interest to return to El Salvador. They remained detained even in this circumstance.

According to Jose, officers called the brothers in early May for processing, which would result in their deportation or detention. Fellow detainees rooted for them.

The outcome was not as anticipated. The brothers were taken to Louisiana for adoption.

For several days, Jose and Josue stayed in holding cells dubbed “hieleras” – Spanish for “ice boxes” – with about 100 people in each. An officer called the brothers’ names to board a flight to El Salvador on May 7 for their mother’s birthday. A second list of names for those who could get off the plane was added after Jose reported. That was Jose’s last hope. However, the brothers’ names were not given.

I was aware that I was leaving behind my mother when the plane took off, Jose said. “Literally everything was staying behind. Our aspirations. Everything .

Stuck in limbo

Jose and Josue, now 21 and 20, re-entered El Salvador nine years after fleeing their home country. They were taken when they applied for asylum, but the US immigration authorities never returned them because they had no passport.

Authorities gave each brother a piece of paper with his name on it as a form of identification. People were waiting for US deportees when Jose and Josue arrived at an immigration processing center. No one was present for them.

“I looked at my brother and said, ‘ Now what? What are we doing? Joe stated.

Their mother sent their grandmother’s childhood friend to pick them up. The brothers couldn’t sleep or eat for the first few nights. According to Amoachi, they have since been diagnosed with PTSD and depression.

A few weeks after Jose and Josue arrived in El Salvador, Josue’s high school in Georgia held its graduation ceremony. He cried in Jose’s arms as they announced his name from his phone rather than walking across the stage.

Jose and Josue long for the chance to reunite with their families after being deported for seven months. Amoachi has filed several appeals on their behalf.

According to Jose, the brothers adhered to the requirements for being in court, checking in with ICE, having good moral behavior, and having no criminal record.

What is the legal path, then? Jose asked. “There isn’t one,” the statement read.

Source: Aljazeera

Leave a Reply