Germans’ slow economic growth, immigration, and the Ukraine war will be the main topics on their minds as they vote on Sunday.

With the last government’s collapse attributed to the debt brake, which strictly restricts government borrowing, German politics has turned into a stumbling block.

Politicians in the third-largest economy in the world are unsure whether this fiscal shackles are preventing growth-boosting investment for the second consecutive year.

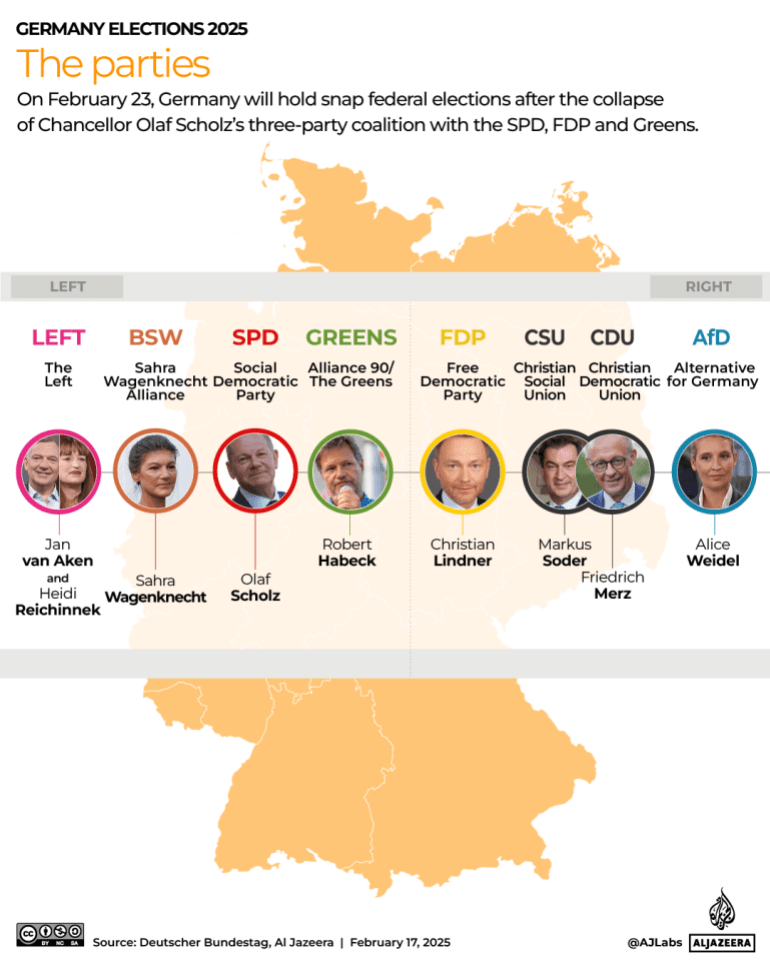

The Christian Democratic Union (CDU), a majority of potential voters still undecided, is unquestionably the party’s clear favorite to become the largest party in parliament, despite a significant number of undecided voters. On the back of an anti-immigration agenda, the far-right Alternative for Germany (AfD) has gained significant popularity in recent years, and polls have placed it in second place.

So what’s a debt brake, and why has it become a major election issue in the eurozone’s largest economy?

What is the debt brake?

The debt brake, or “Schuldenbremse”, caps the federal government’s new borrowing at 0.35 percent of Germany’s gross domestic product (GDP) – except in emergencies – and bars its 16 states from taking on new debt. It aims to stop careless government spending.

In the wake of the world financial crisis, it was introduced in 2009 under Angela Merkel, the previous chancellor. While the rule took effect in 2016, it was suspended during the COVID-19 pandemic and again after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. The law was reinstated a year ago.

In her most recent memoir, Merkel demanded that Germany relax its debt ceiling in response to growing political pressure to change a rigid policy that many economists have found to be unfeasible.

Of the large economies in the eurozone, Germany has the lowest public debt. In Italy, the government debt ratio equals 141 percent of its GDP. In France, it’s 112 percent. In Germany, it’s just 65 percent. In the International Monetary Fund’s (IMF’s) view, debt sustainability is not a pressing issue for Berlin.

And that reflects in the public opinion. According to a survey conducted by Forsa on behalf of the German Council on Foreign Relations in January, 35 percent of Germans are now in favor of lifting strict borrowing restrictions, up from 32 percent in July.

Would more public investment benefit Germany’s economy?

Before this weekend’s elections, polls show that money is at the top of voters ‘ minds. And for good reason. Since 2019 and since 2023, the economy has experienced stagnation. Forecasters also have projected 2025 growth that will decline.

Germany has struggled to withstand the expansion of Chinese market competition, a long-held industrial powerhouse. Industrial work has decreased from 40% in 1990 to 27% today in terms of overall employment.

A potential trade war with the United States might hurt Germany’s sputtering industrial sector even more. Machinery, cars, and industrial tools are its main exports, but demand fluctuates as the world’s economy expands, which would decrease if global tariffs were to rise.

![A worker attaches a part to a Mercedes-Maybach car on a production line]File: Wolfgang Rattay/Reuters]](https://www.aljazeera.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/2024-03-04T132617Z_416940981_RC21F6AVFAIO_RTRMADP_3_MERCEDES-BENZ-SCHOLZ-1740145963.jpg?w=770&resize=770%2C513)

The country’s ageing transport, energy and housing infrastructure also needs upgrading.

Elsewhere, Berlin spends 2.1 percent of its GDP on defence, a touch above NATO’s annual target. But that is thanks to a 100-billion-euro ($105bn) fund created for the war in Ukraine. By 2027, the fund is anticipated to run out, and Berlin will have to make difficult decisions about how to fulfill its NATO obligations without breaking any of its fiscal obligations.

To make matters worse, Germany’s population is ageing. The number of people older than 64 is projected to grow by 41 percent to 24 million by 2050, accounting for nearly one-third of the population. A declining tax base will result from a lower ratio of working-age retirees.

Private investment, which is further impeded by rising corporate tax rates, has also been hampered by concerns about Germany’s economy’s strength.

Still, the debt brake has inhibited successive governments from large-scale spending projects. Public investment has remained stable at about 2 to 3 percent of GDP in recent years, which is a low level in comparison to other regions in the area.

The result is that the motorway authority in Germany has identified 45 billion euros ($47 billion) in investment needs, 800,000 homes are in need of a national shortage, and tens of billions of euros in additional spending will be required annually to meet the stated goal of achieving net-zero carbon emissions by 2045.

Addressing Germany’s numerous structural challenges will cost about 600 billion euros ($628bn) by 2030, according to the German Economic Institute.

Many economists urge the government to use its fiscal sway to boost output.

Fiscal stimulus will have to be made part of any serious efforts to reform and improve the German economy, according to Carsten Brzeski, the Dutch bank’s global head of macro research, in a note.

Finding the fiscal space for all the necessary policies, he continued, “seems impossible, because austerity is the only option available to us.” As such, any new government “will have to agree on looser fiscal policies]i. e., relaxing the debt brake]”, Brzeski said.

What makes it such a crucial election issue?

The governing coalition’s collapse in November was largely due to the debt brake. In order to cover additional spending in Ukraine, Chancellor Olaf Scholz pushed for it to be pushed for in the draft budget. Finance Minister Christian Lindner of the coalition partner Free Democratic Party (FDP) objected to this, however. Lindner was later dismissed.

With no party set to win a straightforward majority in Sunday’s elections, coalition talks are likely to drag on for months. Achieving budget agreements for this and 2026 would be the new government’s top priority.

While Merz, the clear frontrunner to become chancellor, has promised to “uphold” the debt brake, he has also left the door open for change.

“Of course, it can be reformed”, Merz said. “The question is why, for what purpose”. He stated that he would not pursue additional borrowing to fund higher welfare expenses. However, he claimed that if investment was boosted by additional borrowing, the outcome might be different.

The liberal FDP, the conservative CDU, and the far-right AfD want to reduce welfare benefits, preserve existing fiscal rules, and reduce red tape on a broad scale. On the flipside, left-wing parties, such as Scholz’s Social Democratic Party (SPD) and the Greens want the debt brake to be relaxed and for public investment to rise.

The political climate has been affected by the economic slowdown, according to Shahin Vallee, a senior research fellow at the German Council on Foreign Relations.

Many experts think that the rise of the anti-establishment AfD is a result of years of slow economic growth and simmering economic frustration.

![People hold flags during an election campaign rally of Alternative for Germany (AfD) party]File: Karina Hessland/Reuters]](https://www.aljazeera.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/2024-08-31T155318Z_466549284_RC23R9AT1BGP_RTRMADP_3_GERMANY-ELECTION-THURINGIA-AFD-1740145970.jpg?w=770&resize=770%2C513)

What is the future of Germany’s debt brake?

The fiscal system should be modified to allow for small increases in borrowing, according to Germany’s central bank’s long demand. The majority of pundits anticipate only a limited amount of relaxation as opposed to a complete overhaul of the borrowing cap.

But even that won’t be easy. A two-thirds majority in parliament’s upper and lower houses would be necessary for any change to the rule. The AfD, which blames low growth on environmental regulations and mass immigration, opposes fiscal reform as does Lindner’s FDP.

Although Merz recently passed anti-immigration legislation with the AfD’s backing, he has refused to form a coalition government with the party, which is expected to win 20 percent of Sunday’s vote.

As such, Merz will have to form a coalition with one or two of the parties in Scholz’s government, the SPD and the Greens, which are polling in third and second place before the elections.

A possible condition for Merz and the SPD to agree to completely halt some spending items, particularly those related to climate change, would be for them to do so.

Debate brake reform is now “on the table,” according to Vallee, as Germany’s growing consensus requires it to be amended. I think deep down, Merz is secretly happy to be forced into higher public spending by a]left-wing] coalition partner”.

Source: Aljazeera

Leave a Reply