Pakistan said it struck multiple Indian military bases in the early hours of Saturday, May 10, after claiming that India had launched missiles against three Pakistani bases, marking a sharp escalation in their already soaring tensions, as the neighbours edge closer to an all-out war.

Long-simmering hostilities, mostly over the disputed region of Kashmir, erupted into renewed fighting after the deadly April 22 Pahalgam attack in Indian-administered Kashmir that saw 25 tourists and a local guide killed in an armed group attack. India blamed Pakistan for the attack; Islamabad denied any role.

Since then, the nations have engaged in a series of tit-for-tat moves that began with diplomatic steps but have rapidly turned into aerial military confrontation.

As both sides escalate shelling and missile attacks and seem on the road to a full-scale battle, an unprecedented reality stares not just at the 1.6 billion people of India and Pakistan but at the world: An all-out war between them would be the first ever between two nuclear-armed nations.

“It would be stupid for either side to launch a nuclear attack on the other … It is way short of probable that nuclear weapons are used, but that does not mean it’s impossible,” Dan Smith, director of the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, told Al Jazeera.

So, how did we get here? What are the nuclear arsenals of India and Pakistan like? And when – according to them – might they use nuclear weapons?

How tensions have spiralled since April 22

India has long accused The Resistance Front (TRF) – the armed group that initially claimed credit for the Pahalgam attack, before then distancing itself from the killings – of being a proxy for the Lashkar-e-Taiba, a Pakistan-based armed group that has repeatedly targeted India, including in the 2008 Mumbai attacks that left more than 160 people dead.

New Delhi blamed Islamabad for the Pahalgam attack. Pakistan denied any role.

India withdrew from a bilateral pact on water sharing, and both sides scaled back diplomatic missions and expelled each other’s citizens. Pakistan also threatened to walk out of other bilateral pacts, including the 1972 Simla Agreement that bound the neighbours to a ceasefire line in disputed Kashmir, known as the Line of Control (LoC).

But on May 7, India launched a wave of missile attacks against sites in Pakistan and Pakistan-administered Kashmir. It claimed it hit “terrorist infrastructure”, but Pakistan says at least 31 civilians, including two children, were killed.

On May 8, India launched drones into Pakistani airspace, reaching the country’s major cities. India claimed it was retaliating, and that Pakistan had fired missiles and drones at it. Then, for two nights in a row, cities in India and Indian-administered Kashmir reported explosions that New Delhi claimed were the result of attempted Pakistani attacks that were thwarted.

Pakistan denied sending missiles and drones into India on May 8 and May 9 – but that changed in the early hours of May 10, when Pakistan first claimed that India targeted three of its bases with missiles. Soon after, Pakistan claimed it struck at least seven Indian bases. India has not yet responded either to Pakistan’s claims that Indian bases were hit or to Islamabad’s allegation that New Delhi launched missiles at its military installations.

How many nuclear warheads do India and Pakistan have?

India first conducted nuclear tests in May 1974 before subsequent tests in May 1998, after which it declared itself a nuclear weapons state. Within days, Pakistan launched a series of six nuclear tests and officially became a nuclear-armed state, too.

Each side has since raced to build arms and nuclear stockpiles bigger than the other, a project that has cost them billions of dollars.

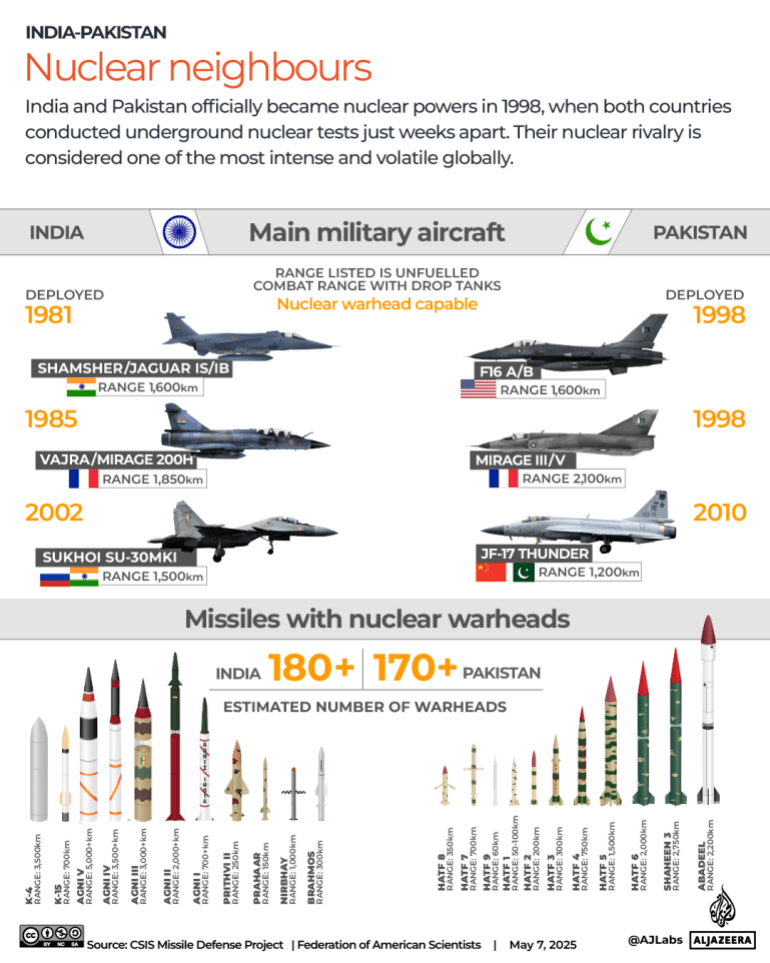

India is currently estimated to have more than 180 nuclear warheads. It has developed longer-range missiles and mobile land-based missiles capable of delivering them, and is working with Russia to build ship and submarine missiles, according to the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS).

Pakistan’s arsenal, meanwhile, consists of more than 170 warheads. The country enjoys technological support from its regional ally, China, and its stockpile includes primarily mobile short- and medium-range ballistic missiles, with enough range to hit just inside India.

What’s India’s nuclear policy?

India’s interest in nuclear power was initially sparked and expanded under its first prime minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, who was eager to use it to boost energy generation. However, in recent decades, the country has solidified its nuclear power status to deter its neighbours, China and Pakistan, over territorial disputes.

New Delhi’s first and only nuclear doctrine was published in 2003 and has not been formally revised. The architect of that doctrine, the late strategic analyst K Subrahmanyam, was the father of India’s current foreign minister, S Jaishankar.

Only the prime minister, as head of the political council of the Nuclear Command Authority, can authorise a nuclear strike. India’s nuclear doctrine is built around four principles:

- No First Use (NFU): This principle means that India will not be the first to launch nuclear attacks on its enemies. It will only retaliate with nuclear weapons if it is first hit in a nuclear attack. India’s doctrine says it can launch retaliation against attacks committed on Indian soil or if nuclear weapons are used against its forces on foreign territory. India also commits to not using nuclear weapons against non-nuclear states.

- Credible Minimum Deterrence: India’s nuclear posture is centred around deterrence – that is, its nuclear arsenal is meant primarily to discourage other countries from launching a nuclear attack on the country. India maintains that its nuclear arsenal is insurance against such attacks. It’s one of the reasons why New Delhi is not a signatory to the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT), as it maintains that all countries uniformly disarm before it does the same.

- Massive Retaliation: India’s retaliation to a first-strike from an aggressor will be calculated to inflict such destruction and damage that the enemy’s military capabilities will be annihilated.

- Exceptions for biological or chemical weapons: As an exception to NFU, India will use nuclear weapons against any state that targets the country or its military forces abroad with biological or chemical weapons, according to the doctrine.

What is Pakistan’s nuclear policy?

- Strategic Ambiguity: Pakistan has never officially released a comprehensive policy statement on its nuclear weapons use, giving it the flexibility to potentially deploy nuclear weapons at any stage of a conflict, as it has threatened to do in the past. Experts widely believe that from the outset, Islamabad’s non-transparency was strategic and meant to act as a deterrence to India’s superior conventional military strength, rather than to India’s nuclear power alone.

- The Four Triggers: However, in 2001, Lieutenant General (Retd) Khalid Ahmed Kidwai, regarded as a pivotal strategist involved in Pakistan’s nuclear policy, and an adviser to the nuclear command agency, laid out four broad “red lines” or triggers that could result in a nuclear weapon deployment. They are:

Spatial threshold – Any loss of large parts of Pakistani territory could warrant a response. This also forms the root of its conflict with India.

Military threshold – Destruction or targeting of a large number of its air or land forces could be a trigger.

Economic threshold – Actions by aggressors that might have a choking effect on Pakistan’s economy.

Political threshold – Actions that lead to political destabilisation or large-scale internal disharmony.

However, Pakistan has never spelled out just how large the loss of territory of its armed forces needs to be for these triggers to be set off.

Has India’s nuclear posture changed?

Although India’s official doctrine has remained the same, Indian politicians have in recent years implied that a more ambiguous posture regarding the No First Use policy might be in the works, presumably to match Pakistan’s stance.

In 2016, India’s then-Defence Minister Manohar Parrikar questioned if India needed to continue binding itself to NFU. In 2019, the present Defence Minister Rajnath Singh said that India had so far strictly adhered to the NFU policy, but that changing situations could affect that.

“What happens in the future depends on the circumstances,” Singh had said.

India adopting this strategy might be seen as proportional, but some experts note that strategic ambiguity is a double-edged sword.

“The lack of knowledge of an adversary’s red lines could lead to lines inadvertently being crossed, but it could also restrain a country from engaging in actions that may trigger a nuclear response,” expert Lora Saalman notes in a commentary for the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI).

Has Pakistan’s nuclear posture changed?

Pakistan has moved from an ambiguous policy of not spelling out a doctrine to a more vocal “No NFU” policy in recent years.

In May 2024, Kidwai, the nuclear command agency adviser, said during a seminar that Islamabad “does not have a No First Use policy”.

As significantly, Pakistan has, since 2011, developed a series of so-called tactical nuclear weapons. TNWs are short-range nuclear weapons designed for more contained strikes and are meant to be used on the battlefield against an opposing army without causing widespread destruction.

In 2015, then-Foreign Secretary Aizaz Chaudhry confirmed that TNWs could be used in a potential future conflict with India.

Source: Aljazeera

Leave a Reply