In order to deport Venezuelans as part of its immigration crackdown, a federal appeals court has found that Donald Trump’s administration unlawfully invoked a wartime law.

The Alien Enemies Act of 1798 was cited by Trump’s use of it to expedite deportations without a fair trial on Tuesday by a majority of the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals.

On several fronts, the choice was remarkable. Trump’s use of the 18th-century law was the first time a federal appellate court had evaluated the use of it, and it also served as a staunch condemnation of his mass deportation campaign from a court known for leaning conservative.

Judge Leslie Southwick refuted Trump’s claim that Tren de Aragua, a member of the Venezuelan gang, was a US invasion, in writing for the three-person bench.

According to Southwick, “we draw the conclusion that the findings do not support the existence of a predatory invasion or incursion.”

Therefore, we believe that petitioners’ arguments are likely to support the improper use of the AEA [Alien Enemies Act] by the petitioners.

The government is only permitted to detain and deport citizens of “hostile” foreign nations when they are at war or when they are “invasion or predatory incursions” under the Alien Enemies Act.

The law had only been used three times, and only once during war, prior to Trump. However, Trump administration officials have cited the law as a justification for the swift deportation of Venezuelan nationals because they constitute a criminal “invasion” across the border.

That claim was refuted by Southwick, who was appointed by Republican President George W. Bush.

There is no evidence that the mass immigration was caused by an armed, organized force, or by any other organization, according to Southwick.

The panel’s decision regarding Trump’s deportations has been made by the highest federal court so far. The US Supreme Court is expected to hear the case eventually.

However, the appeals court’s decision on Tuesday had a narrower scope: it only applies to Texas, Louisiana, and Mississippi, but it may also be used as precedent in other appeals court circuits.

On March 15, Trump first invoked the Alien Enemies Act by publishing an executive order accusing the Tren de Aragua gang of “perpetrating, attempting, and threatening an invasion or predatory incursion” into the US.

The Terrorism Confinement Centre (CECOT), a maximum-security facility known for human rights violations, was visited by his administration on the same day.

Despite a lower judge’s request to forbid his use of the law while the flights were afoot, that transpired.

Although their lawyers claim that many of the Venezuelan migrants on those flights had no criminal records, Trump officials claimed that the Venezuelans were Tren de Aragua members.

The Trump administration has repeatedly claimed that Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro, a long-time adversary of the Republican leader, controls Tren de Aragua in order to meet the requirements for using the Alien Enemies Act.

In a coordinated effort to destabilize the US, Trump has accused Maduro of being the mastermind of a “narco-terrorism enterprise.” However, a declassified US intelligence memo refutes this assertion, claiming that Maduro and Tren de Aragua had no connection to each other.

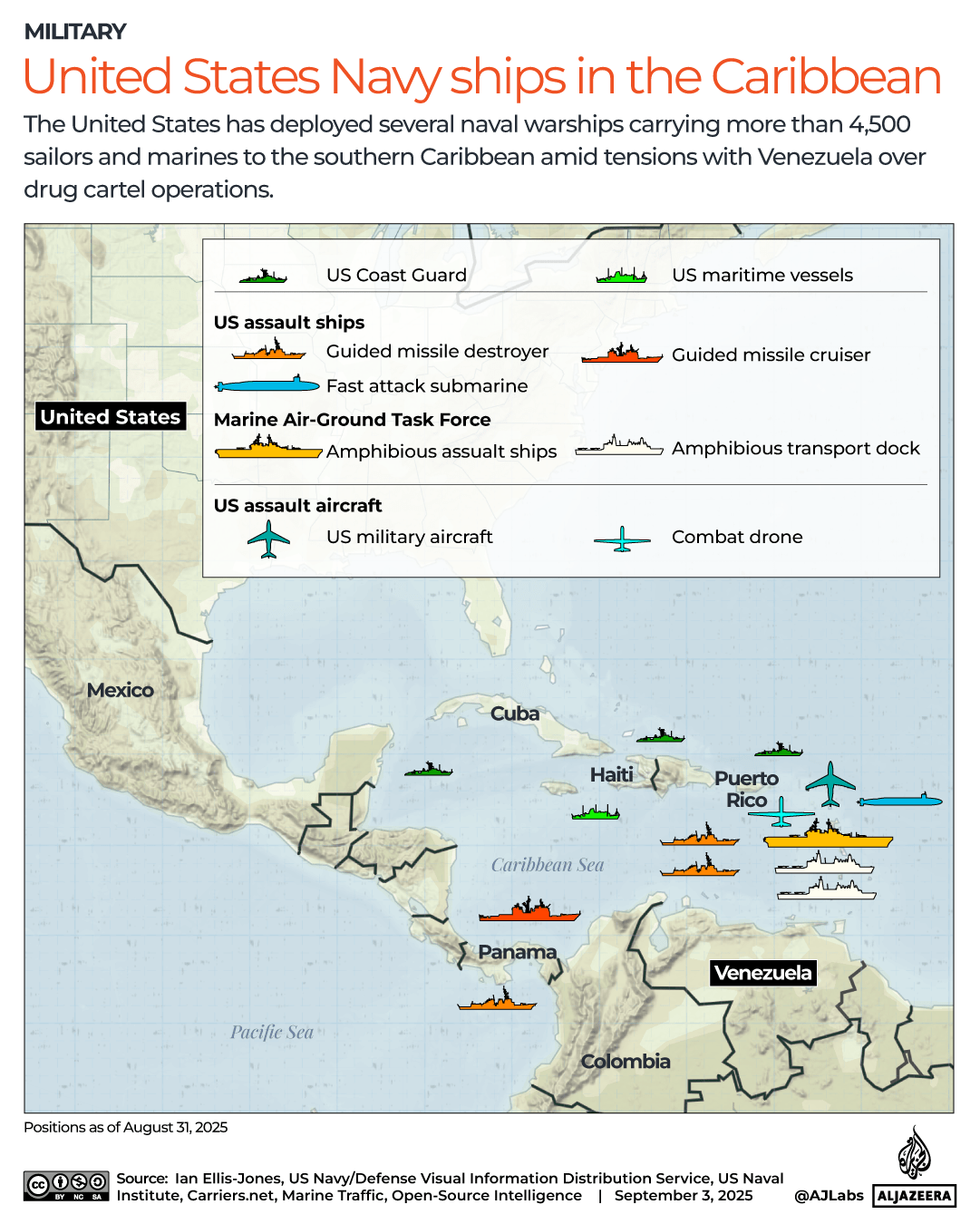

All 11 alleged Tren de Aragua members were killed when the US attacked a boat in international Caribbean waters on Tuesday, according to the US statement. Trump referred to them as “narcoterrorists.”

The US Supreme Court has twice heard cases involving Trump’s use of the Alien Enemies Act, but it has not yet determined whether the Trump administration’s actions are legitimate.

The Supreme Court ruled in April that immigrants should still be able to file for deportations under the law, but that they should still have “reasonable time” to file objections.

Additionally, it recommended that courts elsewhere in the country address these disputes rather than the federal ones where the deportees are being held.

In a second decision, which was made in April, the Supreme Court halted a group of Venezuelan men’s deportations from northern Texas.

The Supreme Court then extended the block in May, criticizing the Trump administration for attempting to remove detainees quickly just one day after issuing deportation notices.

The majority of the opinion was clear: “Notice roughly 24 hours before removal, devoid of information about how to exercise due process rights,” “seen as a muster.”

The Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals was ultimately given the go-ahead for the case.

The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) lawyer Lee Gelernt called the decision a “critically important decision reining in the administration’s view that it can simply declare an emergency without any oversight by the courts” in a statement released following the decision on Tuesday.

The Venezuelan men were represented by the ACLU.

However, one judge, a Trump appointee named Andrew Oldham, dissented from the Fifth Circuit Court decision on Tuesday.

According to Oldham, the president has the right to decide whether the necessary conditions were met in terms of the Alien Enemies Act’s deportations and that they are “matters of political judgment.”