Washington, DC – United States President Donald Trump is set to hold his first “Board of Peace” summit in Washington, DC, an event where the US leader likely hopes to prove the recently launched panel can overcome scepticism – even from those who signed on in support – in the face of months of Israeli ceasefire violations in Gaza.

The summit on Thursday comes nearly three months to the day since the UN Security Council approved a US-backed “ceasefire” plan amid Israel’s genocide in Gaza, which included a two-year mandate for the Board of Peace to oversee the devastated Palestinian enclave’s reconstruction and the launch of a so-called International Stabilization Force.

Recommended Stories

list of 3 itemsend of list

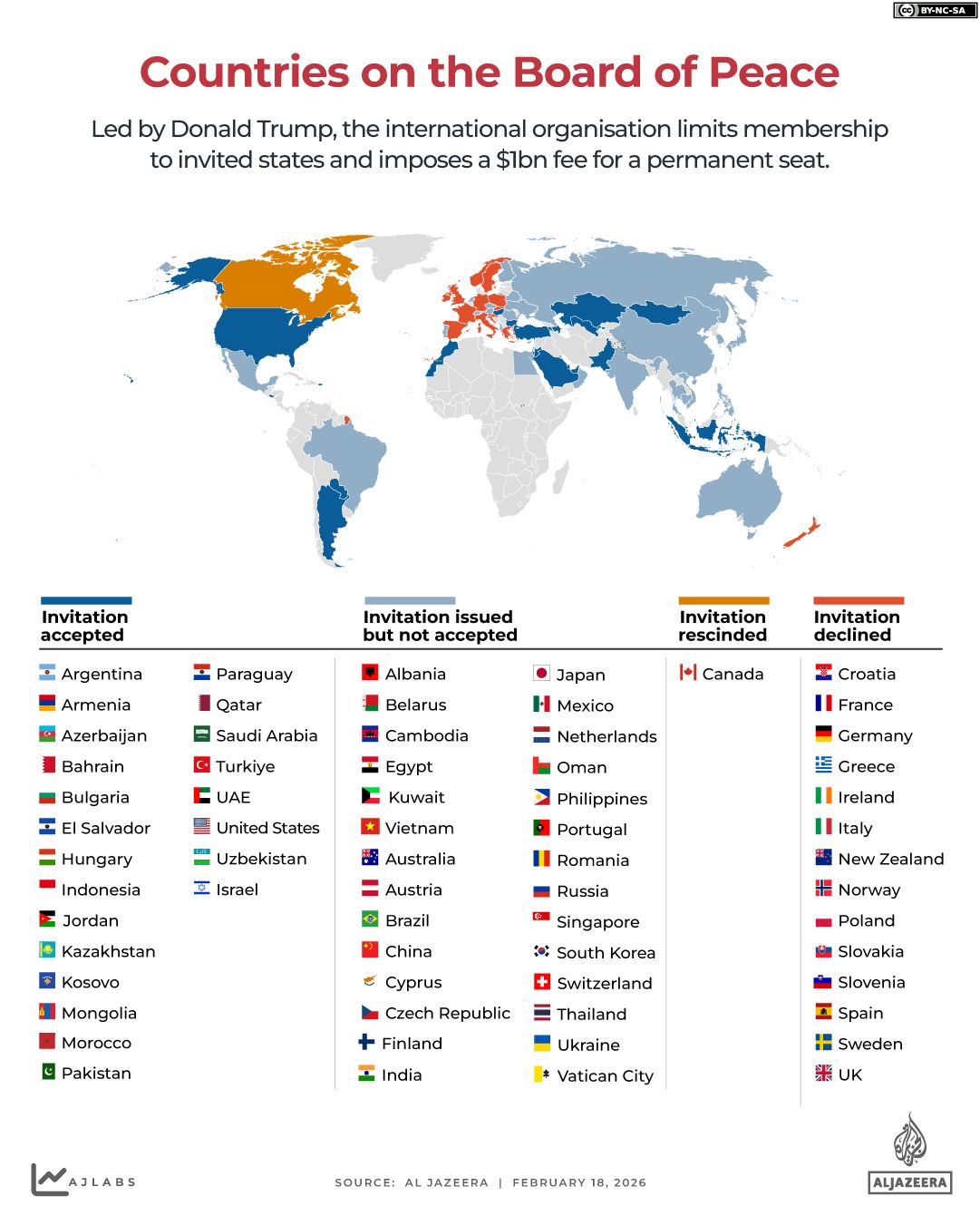

Disquiet has surrounded the board since the November security council vote, with many traditional Western allies wary of the US administration’s apparent wider ambitions, which some have viewed as an attempt to rival the United Nations in a Trump-dominated format.

Others, including countries that have already signed on as members, have raised concerns about the board’s fitness to effect meaningful change in Gaza. Several regional Middle East powers have joined the board, with Israel becoming a late, and to some, disconcerting addition in early February.

As of Thursday’s meeting, the board still has no Palestinian representation, which many observers see as a major obstacle to finding a lasting path forward.

“What exactly does Trump want to get out of this meeting?” Yousef Munayyer, the head of the Israel-Palestine programme at the Arab Center Washington DC, questioned.

“I think he wants to be able to say that people are participating, that people believe in his project and in his vision and in his ability to move things forward,” he told Al Jazeera.

“But I don’t think that you’re going to see any major commitments until there are clearer resolutions to the key political questions that so far remain outstanding.”

‘Only game in town’

To be sure, the Board of Peace currently remains the “only game in town” for parties interested in bettering the lives of Palestinians in Gaza, Munayyer explained, while simultaneously remaining “extremely and intimately tied to the persona of Donald Trump”.

That raises serious doubts over the board’s longevity in what is likely to be a decades-long response to the crisis.

“Regional players that have a serious concern over the future of the region and concern over the genocide have no choice but to really hope that their participation in this Board of Peace allows them to have some leverage and some direction over the future of Gaza in the next several years,” Munayyer said.

He assessed the greatest opportunity for member states who “understand the challenges and understand the context” would be to focus on “what realistically can be achieved in the time period … to focus on the immediate needs and address them aggressively”. That includes health infrastructure, freedom of movement, making sure that people have shelter, pushing for an end to ceasefire violations, to name a few, he said.

At least 72,063 Palestinians have been killed in Gaza since October 7, 2023, with 603 killed since the October 11, 2025, “ceasefire” went into effect. Nearly the entire population of 2.1 million has been displaced, with more than 80 percent of buildings destroyed.

For his part, Trump, who has previously envisioned turning Gaza into a “Middle East Riviera”, struck a positive tone ahead of the meeting. In a post on his Truth Social account on Sunday, Trump touted the “unlimited potential” of the board, which he said would prove to be the “most consequential International Body in History”.

Trump also said that $5bn in funding pledges would be announced “toward the Gaza Humanitarian and Reconstruction efforts” and that member states “have committed thousands of personnel to the International Stabilization Force and Local Police to maintain Security and Peace for Gazans”.

He did not provide further details.

Meanwhile, Trump’s son-in-law, Jared Kushner, who is a member of the panel’s so-called “Gaza executive board”, unveiled the clearest vision yet of Washington’s “master plan” for Gaza in January.

The plan, assembled without any input from Palestinians in Gaza, outlined gleaming residential towers, data centres, seaside resorts, parks, and sports facilities, predicated on the erasure of the enclave’s urban fabric.

At the time, Kushner did not say how the reconstruction plan would be funded. He said it would begin following full disarmament by Hamas and the withdrawal of the Israeli military, both issues that remain unresolved.

Pressure on Israel?

As the US administration stargazes over sweeping construction plans, it is likely to face a starker reality when it meets with a collection of the 25 countries that have signed on as members, as well as several others that are sending observers to the meeting, according to Annelle Sheline, a research fellow in the Middle East programme at the Quincy Institute for Responsible Statecraft.

Any progress to show the board’s “proof of concept” would all-but-surely require asserting unilateral pressure on Israel, she noted.

“Trump is hoping to have countries back up his claim about the $5bn, to get actual commitments on paper,” Sheline told Al Jazeera.

“This is probably going to be challenging, because – especially the Gulf countries – have been very clear that they’re not interested in financing another reconstruction that’s just going to be destroyed again in a few years.”

Israel’s decision to join the board, which Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu had initially opposed, has piqued concerns about further influence over US policy. An act of good faith by the US to advance a more lasting peace could be the inclusion of a Palestinian official on the board, Sheline added.

She proposed widely popular Palestinian political prisoner Marwan Barghouti, who is continuing to serve consecutive life sentences in Israel, as a possible candidate. His release, she said, could be an example of an area where Washington could use its leverage to immediate effect.

In the shorter term, “[interested member states] are largely waiting for the security situation to resolve. Israel violates the ceasefire daily and moves the yellow line”, Sheline said, referring to the demarcation in Gaza behind which Israel’s military was required to withdraw as part of the first phase of the “ceasefire” agreement.

Indonesia’s government has said it is preparing to commit 1,000 troops to a stabilisation force, which could eventually grow to 8,000. But any deployment would likely remain delayed without better ceasefire guarantees, she said.

“It’s still an active warzone,” Sheline added. “So it’s very understandable that even Indonesia, which has hypothetically said it would contribute troops to the stabilisation force, is likely going to say we’re not actually going to do that until the situation is stable.”

An opportunity?

Ensuring an actual ceasefire is enforced – including creating accountability mechanisms for violations – remained “by far the most critical” task for the board’s inaugural meeting, according to Laurie Nathan, the director of the mediation programme at the Kroc Institute for International Peace Studies at the University of Notre Dame.

Trump’s Board of Peace is “not going to be able to play a meaningful reconstruction role in the absence of stability in Gaza, and stability requires adherence to the ceasefire”, he told Al Jazeera.

The next key step – and a major development that could come from Thursday’s meeting – would be a commitment of troops, although Nathan noted any deployment would still likely be deadlocked until a voluntary Hamas disarmament agreement is reached.

On the face of the situation, Trump would appear increasingly incentivised to use Washington’s considerable leverage over Israel to foster a stability in Gaza that the president has closely aligned with his own self-image.

After all, Trump and his allies have regularly portrayed the US president as the “peacemaker-in-chief”, repeatedly touting his success in conflict resolution, even if facts on the ground undermine the claims. Trump has been vocal in his belief that he should be awarded the Nobel Peace Prize.

Still, “Trump’s motivation is multifold,” Nathan explained.

“Does he care about peace? I think he does. Does he want to be a peace broker? Yes. Does he genuinely want the Nobel Peace Prize? Yes.”

“On the other hand, he is performative … it’s never quite clear how much of it is serious for him,” he added. “The further problem is that personal interests are always involved when Trump is doing these things.”

Wider ambitions?

Both Washington’s Western allies and experts in conflict resolution have scrutinised what appears to be the yawning scope of the Board of Peace, far beyond the Gaza purview approved by the UN Security Council last year.

A widely reported founding “charter” sent to invited countries did not directly reference Gaza as it took digs at pre-existing approaches to peace-building that “foster perpetual dependency and institutionalise crisis rather than leading people beyond it”. Instead, it envisioned a “more nimble and effective international peace-building body”.

Critics have further questioned Trump’s singular and indefinite role as “chairman” and sole veto-holder, which largely undermines the principles of multilateralism intended to be enshrined in organisations such as the UN. They have argued that the structure fosters a transactional approach both in dealings with the US government and Trump as an individual.

Richard Gowan, the programme director of global issues and institutions at International Crisis Group, said those concerns are unlikely to subside any time soon. Still, he did not see that precluding European countries from supporting the board’s effort if it is able to make meaningful progress.

“I think, in practical terms, you will see other countries trying to support what the board is doing in the Gaza case, while continuing to keep it at arm’s length over other issues,” he said.

Thursday’s meeting could indicate the Board of Peace’s dynamic and tone going forward.

“If Trump uses his authority under the charter to order everyone around, block any proposals he doesn’t like, and run this in a completely personalistic fashion,” Gowan said, “I think even countries that want to make nice with Trump will wonder what they’re getting into.”