Varun Krishnan was flying from Chennai to Barcelona when Iranian attacks stranded him in Doha. He decided the long desert road to Riyadh was the best way out.

Indian traveller stranded in Qatar takes long road to Riyadh

Varun Krishnan was flying from Chennai to Barcelona when Iranian attacks stranded him in Doha. He decided the long desert road to Riyadh was the best way out.

A group of Democrats in the United States Senate is demanding public hearings on the country’s war against Iran after receiving a series of classified briefings from officials in President Donald Trump’s administration.

Lawmakers say the White House has not clearly explained why the US entered the conflict, what its goals are, or how long it may last.

Republicans currently hold a narrow, 53-47 Senate majority, which gives them the power to control what legislation comes to the floor for debate.

Some Democrats have expressed frustration after the latest closed-door briefing. Trump has not ruled out sending US ground troops into Iran.

“I just came from a two-hour classified briefing on the war,” Senator Chris Murphy from the state of Connecticut said on Tuesday. “It confirmed to me that the strategy is totally incoherent.

“I think this is pretty simple: if the president did what the Constitution requires and came to Congress to seek authorisation for this war, he wouldn’t get it – because the American people would demand that their members of Congress vote no,” he added.

Here is what we know:

Since the US and Israel launched attacks on Iran on February 28, senior officials, including Secretary of State Marco Rubio and Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth, have held several closed-door meetings to brief Congress members on the military campaign and its progress.

Because the meetings are classified, lawmakers are restricted in what they can publicly disclose about the information they received.

Several Democratic senators have said they left the briefings frustrated, arguing that the administration had not provided clear answers about the war’s objectives, timeline or the long-term strategy guiding their approach to the conflict.

Earlier this week, six Democratic senators also called for an investigation into a strike on a girls’ school in Minab, in southern Iran. Reports indicate the attack, which investigators say involved US forces, killed at least 170 people, most of them children.

“There seems to be no endgame,” Democratic Senator Richard Blumenthal said. “The president, almost in a single breath, says it’s almost done, and at the same time, it’s just begun. So this is kind of contradictory.”

Senator Elizabeth Warren from Massachusetts raised concerns about the cost of war.

“The one part that seems clear is that while there is no money for 15 million Americans who lost their health care, there’s a billion dollars a day to spend on bombing Iran,” Warren said on Tuesday.

“The one thing Congress has the power to do is to stop actions like this through the power of the purse,” she added.

Others seem worried that a ground deployment could take place.

“We seem to be on a path toward deploying American troops on the ground in Iran to accomplish any of the potential objectives here,” Blumenthal, of Connecticut, told reporters after Tuesday’s classified briefing.

“The American people deserve to know much more than this administration has told them about the cost of the war, the danger to our sons and daughters in uniform and the potential for further escalation and widening of this war,” he added.

Republicans, who have slim majorities in both houses of Congress, have almost unanimously backed Trump’s campaign against Iran, with only a handful expressing doubt about the war.

Some Republican leaders say the strikes are necessary to curb Iran’s military capabilities, missile programme and regional influence.

They have also argued that the operation is limited in scope and designed to weaken Iran’s ability to threaten US forces and allies in the region.

Republican Representative Brian Mast of Florida, chairman of the House Foreign Affairs Committee, last week publicly thanked Trump for taking action against Iran, saying the president is using his constitutional authority to defend the US against the “imminent threat” posed by Tehran.

But some Republican members of Congress have voiced concerns.

Representative Nancy Mace from South Carolina said she did “not want to send South Carolina’s sons and daughters into war with Iran”, in a post on X.

Rand Paul, a Republican senator from Kentucky, accused the Trump administration of changing its narrative and rationale for the war on a daily basis.

“We keep hearing new reasons for war with Iran—none convincing,” he wrote on X. “‘Free the oppressed’ sounds noble, but where does it end? We’ve been told for decades Iran is weeks from a nuke. War should be a last resort, not our first move. A war of choice is not my choice.”

The dispute has revived a long-running debate in Washington, DC, about the limits of presidential war powers.

Under the US Constitution, Congress has the authority to declare war, but modern presidents have frequently launched military operations without formal congressional approval, often citing national security or emergency threats.

The law allows the president to deploy US forces for up to 60 days without congressional authorisation, followed by a 30-day withdrawal period if Congress does not approve the action.

Some lawmakers and legal experts say the war on Iran highlights the need for stronger congressional oversight of military action.

“In the 1970s, we adopted something called the War Powers Resolution that gives the president limited ability to do this,” said David Schultz, a professor in the political science and legal departments at Hamline University.

“And so, either you could argue that what the president is doing violates the Constitution by… not [being] a formally declared war; or b, it exceeds his authority, either as commander-in-chief or under the War Powers Act,” he added.

“And therefore, you could argue that domestically, his actions are illegal and unconstitutional,” Schutlz said.

The Trump administration has argued that the February 28 strikes were justified as a response to an “imminent threat”, a rationale often used by presidents to justify military action without prior congressional approval.

Australia has confirmed that two more members of the Iranian women’s football team have received humanitarian visas, after five players were earlier granted asylum over concerns for their safety should they return to Iran, following the team failing to sing their national anthem before a recent match.

A player and a member of the team’s support staff decided to stay in Australia after seeking asylum, Minister for Home Affairs Tony Burke told reporters on Wednesday.

list of 4 itemsend of list

The pair has now joined five other team members granted humanitarian visas on Tuesday, Burke told reporters.

He said the pair sought asylum before the team departed the country late on Tuesday night, adding that all the women were taken aside individually by Australian officials and interpreters, without Iranian minders present, and offered asylum as they passed through security at Sydney airport.

“They were given a choice,” said Burke, who later posted images of the players on social media.

“In that situation, what we made sure of was that there was no rushing, there was no pressure,” he said.

Burke also said that some people linked to the team were not offered asylum, without providing details. One member of the delegation delayed boarding the departing flight from Sydney while they contacted family members and deliberated about staying in Australia, Burke said.

“We weren’t sure which way that person would go,” he said. “That individual ultimately made their own decision.”

The seven team members who had requested asylum have received temporary humanitarian visas, which is a pathway to permanent residency in Australia, Burke said.

According to the Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC), the visas offered to the team members are valid for 12 months and are similar to those granted to applicants from Ukraine, Palestine and Afghanistan.

The team’s departure from their hotel in Australia’s Gold Coast and arrival at the domestic airport in Sydney before their international departure took place amid protests, as Iranian Australians sought to prevent the women from leaving the country, citing fears for their safety in Iran.

Concerns about the players’ safety emerged after Iranian state television labelled the team “traitors” for refusing to sing the national anthem before their first Asia Cup match in Australia. The team later sang the anthem at other matches.

However, the office of Iran’s general prosecutor said on Tuesday that the remaining members of the team were invited home “with peace and confidence”, Iranian media reported.

“These loved ones are invited to return to their homeland with peace and confidence, and in addition to addressing the concerns of their families,” the general prosecutor’s office was quoted as saying by Iran’s Tasnim news agency.

Iran’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs spokesperson, Esmaeil Baghaei, also urged the players to “come home”.

“To Iran’s women’s football team: don’t worry – Iran awaits you with open arms,” Baghaei wrote on X on Tuesday.

The Iranian team joined the Women’s Asian Cup tournament in Australia just as the US and Israel launched their war on Iran, killing the country’s supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, and many senior officials.

At least 1,255 people have been killed in the US-Israeli war on Iran, which has entered its 11th day and has seen devastating air strikes on the capital, Tehran, and other cities, as well as key infrastructure and civilian sites.

The high-profile offer of asylum to the football players also comes as the Australian government moved to introduce legislation to ban people from certain countries travelling to Australia who authorities fear might overstay their visa due to the war in the Middle East.

According to the ABC, the proposed law would allow the government to stop people from nominated countries entering Australia for up to six months, even if they already have a valid temporary visa.

The Australian Greens party said on Tuesday the law was “clearly aimed at preventing people from Iran from seeking safety in Australia”.

“We know who this is aimed at by Labor, it’s aimed at the people of Iran, the people of Lebanon, the people of Qatar and the entire Middle East. It is clearly designed to be a Trump-like mass visa freeze,” said Greens Senator David Shoebridge.

Kon Karapanagiotidis, chief executive of the Asylum Seeker Resource Centre, said the Australian government was acting hypocritically.

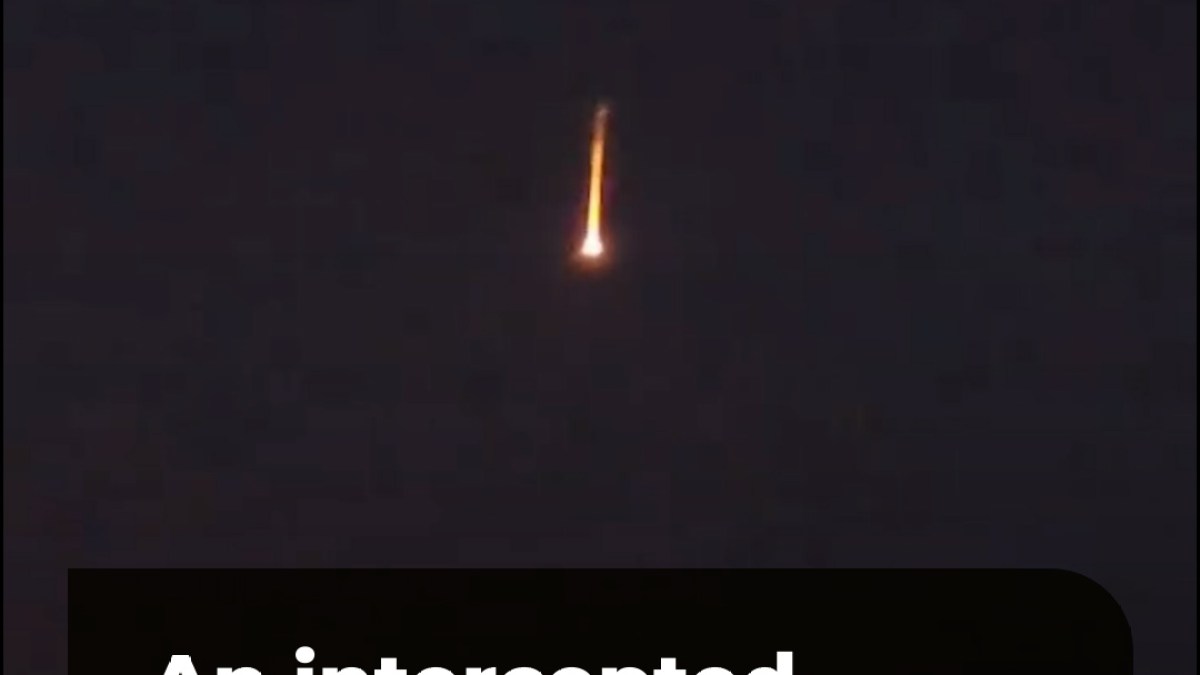

Footage from the ground in Erbil, Iraq shows several drones over the city’s airspace and the wrecking of a drone falling through the sky onto the city.

The Iranian military released footage of missile launches from what it described as a wave of heavy, multi-warhead projectiles targeting Iraq, Bahrain, and Israel. Interceptions were seen in the skies over Israel though reports have emerged of a hit on Tel Aviv.

A new report has expressed alarm at what it describes as backsliding press freedoms across the Americas, with the United States seeing the steepest decline.

The Inter American Press Association (IAPA) released its latest press freedom index on Tuesday, ranking last year as the lowest point for freedom of expression since the report began in 2020.

list of 3 itemsend of list

Researchers found that the Americas have experienced a “dramatic deterioration” in unrestricted speech, according to the report.

“This is one of the worst years for journalism in the region, marked by murders, arbitrary arrests, exile, and rampant impunity in countries such as Mexico, Honduras, Ecuador, Nicaragua, El Salvador, Guatemala, Colombia, Cuba, and Venezuela,” the report said.

It added that enhanced restrictions on free speech have occurred in countries of various ideological persuasions, whether right-wing or left-wing.

The US, however, was singled out as an area of “alarming decline”. In a ranking of 23 countries across the hemisphere, the US dropped from fourth place to 11th, indicating that journalists operate with increased restrictions.

Changes under President Donald Trump, who returned to office last year, were cited as a primary factor.

“Even though journalistic practice in the United States remains protected by the Constitution and laws, last year’s events saw the erosion of safeguards,” the report explained.

Trump, it said, had contributed to the “stigmatisation of critical journalism”. The report also pointed to developments like cuts to public media funding and the closure of Voice of America, a government-funded broadcaster, as detriments to the free press.

In total, the report tallied 170 attacks against journalists in the US last year, and it cited interactions with federal immigration agents as an area of concern.

The report also noted that Nicaragua and Venezuela continue to rank as “without freedom of expression”.

In Venezuela’s case, for instance, it cited the closure of more than 400 radio stations and the detention of 25 journalists in the wake of the controversial 2024 presidential election.

On a scale of 100, the report ranked press freedom in the country at 7.02. It remains in last place on the report’s list of 23 countries.

El Salvador also dropped in the index’s latest evaluation, now in 21st position on the press freedom list, just ahead of Nicaragua and Venezuela.

In an accompanying statement, Sergio Arauz, the president of the Association of Journalists of El Salvador (APES), denounced what he called the “escalating repression” under the government of President Nayib Bukele.

Arauz noted that 50 Salvadoran journalists had been pushed into exile in the last year amid a campaign of harassment by the government.

“There are no possibilities of practicing journalism fully without facing consequences when there is an Executive branch with virtually unlimited powers and no effective legal oversight,” said Arauz.

Since 2022, Bukele and his government have placed the country under a state of emergency that suspended key civil liberties and granted wide latitude to state security forces, in the name of addressing crime.

Tuesday’s report pointed to the state of emergency as a factor in undermining free speech, and also cited El Salvador’s new Foreign Agents Law, which gives the government the power to dissolve organisations that receive funding from abroad.

El Salvador is one of eight nations categorised in the index as “high restriction”, along with Ecuador, Bolivia, Honduras, Peru, Mexico, Haiti and Cuba.