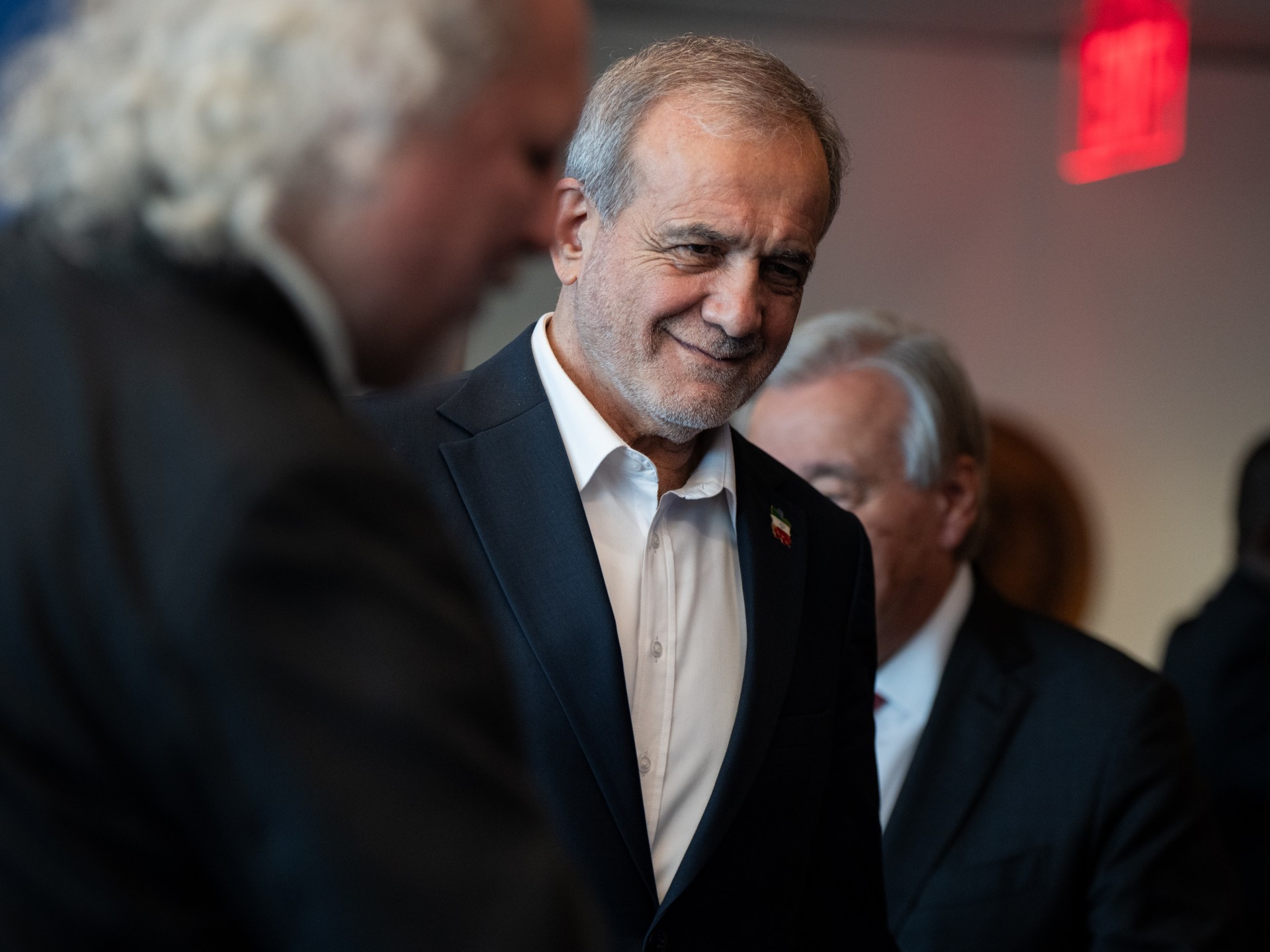

Iranian President Masoud Pezeshkian has held a phone call with Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman (MBS) after a United States aircraft carrier arrived in the region amid growing fears of a new conflict with Israel or the US.

The US has indicated in recent weeks that it is considering an attack against Iran in response to Tehran’s crackdown on protesters, which has left thousands of people dead. US President Donald Trump has sent the USS Abraham Lincoln aircraft carrier to the region.

Recommended Stories

list of 3 itemsend of list

Pezeshkian hit out at US “threats” in the call with Saudi Arabia’s leader on Tuesday, saying they were “aimed at disrupting the security of the region, and will achieve nothing other than instability”.

“The president pointed to recent pressures and hostilities against Iran, including economic pressure and external interference, stating that such actions had failed to undermine the resilience and awareness of the Iranian people,” a statement from Pezeshkian’s office said on Tuesday.

The statement also said that Prince Mohammed “welcomed the dialogue and reaffirmed Saudi Arabia’s commitment to regional stability, security, and development”.

“He emphasised the importance of solidarity among Islamic countries and stated that Riyadh rejects any form of aggression or escalation against Iran,” it said, adding that he had expressed Riyadh’s readiness to establish “peace and security across the region”.

The official Saudi Press Agency (SPA) reported after the call that Prince Mohammed told Pezeshkian that Riyadh would not allow its airspace or territory to be used for military actions against Tehran.

“HRH the Crown Prince affirmed during the call the Kingdom’s position in respecting the sovereignty of Iran, stressing that the Kingdom will not allow its airspace or territory to be used for any military actions against Iran or for any attacks from any party, regardless of their origin,” SPA reported.

“HRH the Crown Prince also affirmed the Kingdom’s support for any efforts aimed at resolving disputes through dialogue in a manner that enhances security and stability in the region,” the news agency added.

“The Iranian president expressed his gratitude to the Kingdom for its steadfast position on respecting the sovereignty and territorial integrity of Iran and conveyed his appreciation for the role undertaken by HRH the Crown Prince in exerting efforts and initiatives to achieve security and stability in the region.”

‘Neighbouring countries are our friends’

The call between the two leaders came after Trump repeatedly threatened to attack Iran during Tehran’s deadly crackdown on antigovernment protests this month. Last week, the US president dispatched an “armada” towards Iran but said he hoped he would not have to use it.

Delivering a speech in Iowa on Tuesday, Trump again said that a large “armada” was heading towards Iran and repeated his threats, saying that Tehran should yield to US demands.

“By the way, there’s another beautiful armada floating beautifully toward Iran right now. So we’ll see,” Trump said in his speech.

“I hope they make a deal. I hope they make a deal. They should have made a deal the first time. They’d have a country,” he said, in an apparent reference to US attacks on Iran last June.

Amid growing fears of a new war, a commander from Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) on Tuesday issued a warning to his country’s neighbours.

“Neighbouring countries are our friends, but if their soil, sky, or waters are used against Iran, they will be considered hostile,” Mohammad Akbarzadeh, political deputy of the IRGC’s naval forces, was quoted as saying by the Fars news agency.

Israel carried out a wave of attacks on Iran in June 2025, targeting several senior military officials and nuclear scientists, as well as nuclear facilities. The US then joined the 12-day war to bombard three nuclear sites in Iran.

The war came on the eve of a round of planned negotiations between the US and Iran over Tehran’s nuclear programme.

Since the conflict, Trump has reiterated demands that Iran dismantle its nuclear programme and halt uranium enrichment, but talks have not resumed.

On Monday, a US official said that Washington was “open for business” for Iran.

“I think they know the terms,” the official told reporters when asked about talks with Iran. “They’re aware of the terms.”

Ali Vaez, director of the Iran Project at the International Crisis Group, told Al Jazeera that the odds of Iran surrendering to the US’s demands are “near zero”.

Iran’s leaders believe “compromise under pressure doesn’t alleviate it but rather invites more”, Vaez said.

But while the US military builds up its presence in the region, Iran has warned that it would retaliate if an attack is launched.

Iran’s Foreign Ministry spokesperson warned on Tuesday that the consequences of a strike on Iran could affect the region as a whole.