Somaliais are protesting President Donald Trump’s recent remarks that they called their nation “a place where people just run around killing each other.”

Published On 4 Dec 2025

Somaliais are protesting President Donald Trump’s recent remarks that they called their nation “a place where people just run around killing each other.”

Published On 4 Dec 2025

For the first time in a home match since 2012, Nathan Lyon was withdrawn from the Australian side, and Pat Cummins, the hosts’ skipper, was also unavailable for the second Ashes Test in Brisbane.

Cummins is still a patient patient as he recovers from a back injury despite speculation that he might make a surprise comeback despite not being named in the squad.

The hosts chose an all-seam attack for the day-night Test at the Gabba, but the shock was caused by Lyon’s omission, which is Australia’s third-highest wicket-taker in Test cricket.

The decision was described as “bombshell” on Cricket Australia’s website.

Michael Neser, a seamer, received a third cap as a result. Neser’s only two previous Test appearances were pink-ball matches.

Stand-in Australia captain Steve Smith said: “Pat was close. He has succeeded in every way. He’s tracking well for the upcoming game, despite our initial concern that it might have been a little risky.

Only Lyon and the legendary seamer Glenn McGrath have Test-tried to score more Test wickets than the legendary Shane Warne. The 38-year-old needs two more to move past McGrath’s 562 and to the top of the list.

In January 2012, Lyon was last excluded from a home Test against India at the Waca. He had won 71 home tests in a row.

Given Lyon’s history at the Gabba and how quickly this ball softens, ex-Australian spinner Alex Hartley said in Test Match Special.

“You might need someone to hold up an end, but Labuschagne can bowl a little, because they may not have enough part-time spinners to do that.”

Lyon has now been cut out of the Australia XI twice in three Test matches, and he was also excluded from the side’s 176-run victory over West Indies in Jamaica in July.

Lyon responded, “Disappointed on a number of levels, based on that decision. I still firmly believe that I am capable of playing a role in any situation.

Every cricket player should have that conviction in mind, and I want to play every game for Australia.

Neser lengthens Australia’s batting order to number eight and has the knowledge that Gabba is his home ground, but only Warne and McGrath surpass Lyon in Brisbane in terms of wickets.

Josh Inglis, who was born in Leeds, replaced Usman Khawaja in the Australian team as expected. Inglis is listed at number seven while Travis Head is still the opener.

Will Jacks, an injured fast bowler, will replace Mark Wood in the England XI that had already been confirmed.

England has won at the Gabba twice since 1986, and they have never lost in any of their previous three Australian pink-ball matches.

The rehearsed beckoning of street vendors and the restless cries of two young children break the silence of a narrow alley in Srinagar, the main city in Indian-administered Kashmir.

“Auntie, please take me to my mother, the police took her away”, shouts three-year-old Hussein, as he and his sister Noorie, a year younger than him, cling to the window of their one-room house, their faces pressed against rusted iron bars.

list of 4 itemsend of list

Since their mother, a Pakistani national, was forced to leave and was deported more than seven months ago, the pair have been yelling like that almost every passing by, according to their father, Majid*.

The family’s ordeal began a week after half a dozen gunmen, a couple of them alleged to be Pakistani nationals, stormed a scenic tourist spot in Indian-administered Kashmir’s Pahalgam area and shot 26 people dead on April 22, 2025 in one of the worst attacks in the disputed region.

India and Pakistan own a portion of Kashmir’s Muslim-majority region, but their nuclear-armed neighbors assert full control over the region, and regional superpower China also holds some of the landmass. Since India’s independence from British rule and its partition to create the state of Pakistan in 1947, the two countries have fought two of their three full-scale wars over Kashmir.

An armed uprising against New Delhi’s rule on the Indian side erupted in the late 1980s, which has since claimed tens of thousands of lives, most of them civilians. The rebellion saw the deployment of nearly a million Indian soldiers, making it one of the world’s most militarised regions. The rebels want to combine Kashmir with Pakistan, which has a Muslim majority, or to create an independent country.

The anti-India sentiments in Kashmir intensified in 2019 when Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s Hindu majoritarian government scrapped a law that granted the region partial autonomy in matters of land ownership and livelihoods, and split it into two “union territories” to be directly governed by New Delhi. Since then, suspected Kashmiri rebels have launched numerous attacks on Indian government employees and security personnel. India accuses Pakistan of training and financing the rebels, but Islamabad dismisses the charge, claiming it only provides diplomatic backing to Kashmir’s struggle.

India immediately put a key water treaty in abeyance, suspend bilateral trade, and put Pakistan on hold for the Pahalgam attack as well. Two weeks after the killings, in early May, India and Pakistan engaged in an intense four-day air war, each striking the other’s military bases. Before the neighbours agreed to a ceasefire, thousands of people were killed on both sides: India claims it only targeted “terrorists” in Pakistan, while Islamabad claims civilians are primarily the victims.

But seven months later, the pause in fighting has meant little for hundreds of families, like Majid’s and Samina’s, that were broken apart by one of India’s moves.

India revoked all visas issued to Pakistanis living in India, including those for medical and diplomatic purposes, giving them a May 1 deadline of April 29, 2025, and closing the Attari-Wagah border in Punjab province’s Amritsar district.

Nearly 800 Pakistanis – many of them married to Indian nationals in Kashmir and other parts of India – were deported.

The wait is awaited for relatives on both sides of the border because authorities don’t know whether those families will ever reunite.

Samina, his 38-year-old cousin from Pakistan, and Majid got married in 2018.

Despite tense relations between their countries, their marriage was not especially rare. Many Muslims and Hindus to India left behind relatives on both sides of the border when millions of them migrated to the newly formed Pakistan in 1947. Over the years, these blood ties gave rise to cross-border marriages between citizens of the two countries.

However, Samina was summoned to the Dalgate neighborhood of Srinagar on April 28. Noorie and Hussein slept on their laps as the couple met the police officer. When the children realized their mothers were gone, their father had brought them back home.

Samina was detained at the police station and informed that she would be deported to Pakistan — she is originally from Lahore — the next day.

Majid said he is still struggling to process the events that altered his life, which included his bedroom and kitchen, in a dimly lit room.

He used to work as a waiter for a nearby restaurant, where he made about $70 per month. But since his wife was taken away, he has not been able to leave his little children alone. He is currently unemployed.

“I have not slept properly for six months now. My entire time is spent tasked with raising the kids. I cannot think about doing anything else”, he told Al Jazeera.

Majid claims he can’t even go out and buy groceries because he is locked up in his room. “Sometimes, I think of ending my life”, he said. But as I go home, I stop and think about how they would care for them.

Majid’s children, Hussein and Noorie, also do not know when they will be able to see their mother.

They have been traumatized by their sudden separation from Samina. They call out to their mother in sleep”, Majid told Al Jazeera as he made a futile attempt to distract his children by showing them cartoons on his mobile phone.

They are only aware that the police removed her. Whenever they see any police or army officer, they ask them to bring their mother back”.

Samina is currently dealing with health issues in Pakistan after being forcibly separated from her children. Her blood pressure is unstable due to stress. She occasionally gets hospitalized. Her blood pressure isn’t normalising”, said Majid.

When questioned about the deportations, Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) spokeswoman Shazia Ilmi claimed that the concerns about national security led to the decisions. Those deported were Pakistani nationals, she emphasised, and often were “married to those who have been found involved in terrorism and activities that are antinational”, she told Al Jazeera.

Therefore, Pakistanis cannot enter India and support these activities in this way. Why should India have Pakistani nationals”? she stated.

When pressed to present evidence in support of her allegation that deportees were often married to those involved in “terrorism”, Ilmi accused Al Jazeera , of having a “dubious agenda”. She said, “I believe you have a nasty agenda to find things against India and the Indian government, and it will not work.”

In the densely populated district of what is known as Old Delhi, Daryaganj, where Muhammad Shehbaz is a 32-year-old resident. In 2014, he married his maternal cousin from Pakistan, 27-year-old Erum. Erum had been living in India for a long time before moving to Pakistan to meet her family, who had just turned three.

That was in March 2020 – just 10 days before a lockdown and travel restrictions were imposed in the wake of the coronavirus pandemic. Her Indian visa expired while Rum was forced to extend her stay in Pakistan.

After the lockdown was lifted, Shehbaz tried hard to secure another Indian visa so that Erum could return. She received a final rejection in April of this year after five years of repeated rejections. After more than five years of separation, an elated Shehbaz was finally going to be reunited with his family.

On April 17, Erum arrived in New Delhi. Twelve days later, the Pahalgam attack happened. On April 29, she was returned to Pakistan.

“After so many years of separation, hard work and longing, she had finally come home. I had forgotten everything that had happened in my world. And then, in the blink of an eye, it all collapsed again. She was taken away, leaving me vulnerable and drowning in despair, Shehbaz told Al Jazeera.

“When the police came to our home and informed us about Erum’s deportation, I became numb. My son was groping uncontrollably. The struggles I faced all these years to reunite my family are beyond words. And now it seems like everything was lost.

Almeer, now nine, first grew up for years without his father and has now been torn away from his mother. Shehbaz, who owns a small jewelry store, worries about the future.

“He has grown frail and quiet, not expressing much, but I can see he is shattered inside”, Shehbaz told Al Jazeera. Why are regular citizens shoved to the wall when the two countries are at war with one another? What is our fault”?

Back in Indian-administered Kashmir, Fazl‑u‑Rehman, 62, does not know if he might be able to see his wife, Parveena, who was deported in April to Pakistan, a country she had not seen in more than four decades.

Parveena, 65, was born in Karachi, Pakistan. But she never went back after marrying Rehman in 1982, as she built a life with her husband and children in Baramulla district.

Rehman now fears that he might pass away without seeing her.  , “Our home has been divided. Everything is in disrepair. I don’t know how many years I will live”, he told Al Jazeera, his voice choking.

Rehman and Parveena have two daughters – the elder one, Afreen, is married, while Soliha, 27, is at home, looking after her ageing parents while also pursuing a master’s degree in political science.

She told Al Jazeera, “I managed to manage the household responsibilities alone while I missed my second semester midterm exams in July.” “I have to do it all alone – getting medicines, groceries and other household chores. I had to give up my education when I was left with no other choice.

Soliha said her mother has been undergoing treatment for heart disease in Kashmir. She also lacks financial support and immediate relatives in Pakistan, where she continues to receive treatment. She said her mother lives in Karachi with a distant relative, who is paralysed.

“She needs someone to look after her,” she said. If anything happens to my mother there, the Indian government would be responsible”, she said.

Why are we being punished for the crime that was committed by another person? My education and career are at stake. Because of my mother’s deportation, I have mental health issues.

Her father, Rehman, intervened. In Kashmir, there are between 700 and 800 armed forces. If they couldn’t prevent the]Pahalgam] attack, how are civilians being held responsible for it”? He yelled in rage.

Parveen urged the government to “stop punishing your own citizens” and demanded the return of their loved ones.

Abdullah* says he has been forced to rebuild his life that fell apart after his wife, Tamarah*, 25, was deported on April 29. He claims that his twins, Ayan and Atif, who are only 18 months old, no longer play, laugh, or eat as they once did. One of the twins was still breastfeeding when Tamarah was deported.

Tamarah and Abdullah, a 38-year-old public bank manager in Kashmir’s Kupwara district, wed in 2018. As she was driven to the Attari-Wagah border for deportation, Abdullah took his children and followed the police van in his car all the way from Kupwara to Amritsar, a distance of more than 500km (324 miles).

He told Al Jazeera, “I cried on the way, pleading helplessly with the police to at least let the children see their mother one last time.” “But they didn’t even allow us a proper goodbye”.

For the children, the first two months were “nothing short of hell.”

“After the sudden separation from their mother, their health began to deteriorate. He continued, “They had frequent fevers and nausea,” adding that he had not been to office in the last six months, and that one or both of the children needed hospitalization.

“Everything is disrupted. The world has changed. I have never felt so helpless in my life”, he said.

Even lawyers, according to Abdullah, declined to hear about the case of his children, who were separated from their mothers. He said the lawyers said no legal action could proceed without permission from the federal Ministry of Home Affairs. Abdullah claimed to have written to Prime Minister Modi and other New Delhi and Kashmir officials out of desperation, but was never received a reply.

Due to the tensions between India and Pakistan, human rights activists claim that there is no justification for punishing innocent civilians.

“Ordinary people hold no enmity towards each other. Why should political or diplomatic conflict cause them harm? said Shabnam Hashmi, a New Delhi-based activist. Civilians must never be the victims in a conflict. To separate a child from their mother is cruel, traumatic, and utterly inhuman – a clear violation of human rights”.

The deportation of Pakistanis is unjustified and unfortunate, according to Waheed Para, a Kashmiri lawmaker from the Peoples Democratic Party.

“After Kashmir’s conversion into a union territory, our ability to influence or resolve such issues has been severely limited. He told Al Jazeera, referring to the federal government in New Delhi, “We can raise our voices and try to intervene, but we remain largely powerless in the face of decisions made elsewhere.”

“In cross-border shelling, civilians lose lives and homes. Unfortunately, innocent people, children, and women continue to suffer as a result of India and Pakistan’s geopolitical conflict, Paragraph added.

Al Jazeera reached out to the Ministry of Home Affairs for their response, but did not receive any reply.

The deportation of Pakistanis has no logical connection to the Pahalgam attack, according to Colin Gonsalves, a rights activist and lawyer for the Supreme Court.

“Linking them to Pahalgam]attack] is simply an excuse and a deeply flawed one … The government may claim it is a fallout of Pahalgam, but that claim is not only misleading, it’s dangerous”, he told Al Jazeera.

They were deported simply because they were Muslims and Pakistanis, which shows a bias toward both.

Back in Kupwara, Abdullah wipes the tears rolling down his cheeks, struggling to speak as he recollects the months since his wife Tamarah was deported.

“What the Indian government did to us is comparable to what the attackers did in Pahalgam,” the statement read. They destroyed our families and homes too”, he said. Why are our children receiving punishment? What did they do”?

New Delhi, India – Russian President Vladimir Putin is visiting India starting Thursday for the first time since Moscow’s war on Ukraine broke out more than four years ago, even as a renewed push by the United States to end the conflict appears to have stalled.

Putin’s 30-hour speed trip also coincides with a tense turn in relations between Washington and New Delhi, with the US also punishing India with tariffs and a sanctions threat for its strong historic ties with Russia and a surge in its purchase of Russian crude during the Ukraine war.

That tension has, in turn, made India’s longstanding balancing act between Russia and the West an even more delicate tightrope walk.

Since gaining independence from Britain in 1947, India has tried to avoid getting locked into formal alliances with any superpower, leading the non-aligned movement during the Cold War, even though in reality it drifted closer to the Soviet Union from the 1960s. Since the end of the Cold War, it has deepened strategic and military ties with the US while trying to keep its friendship with Russia afloat.

Yet, Russia’s war on Ukraine has challenged that balance – and Putin’s visit could offer signs of how Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi plans to juggle New Delhi’s competing relationships without sacrificing any of them.

Putin is expected to land on Thursday evening and head for a private dinner with Modi at the prime minister’s residence in the heart of the Indian capital, New Delhi.

On the morning of Friday, December 5, Putin is scheduled to visit Rashtrapati Bhavan, the presidential palace, for a guard of honour and a meeting with India’s ceremonial head of state, Droupadi Murmu. He will then, like all visiting leaders, travel to Raj Ghat, the memorial to Mahatma Gandhi.

Then, Putin and Modi will meet at Hyderabad House, a complex that hosts most leadership summits for the latest chapter of an annual India-Russia summit. After that, they are scheduled to meet business leaders, before attending a banquet thrown in Putin’s honour by Murmu, the Indian president.

Earlier, the Kremlin said in a statement that Putin’s visit to India was “of great importance, providing an opportunity to comprehensively discuss the extensive agenda of Russian-Indian relations as a particularly privileged strategic partnership”.

Putin will be joined by Andrei Belousov, his defence minister, and a wide-ranging delegation from business and industry, including top executives of Russian state arms exporter Rosoboronexport, and reportedly the heads of sanctioned oil firms Rosneft and Gazprom Neft.

The visit comes as India and Russia mark 25 years of a strategic partnership that began in Putin’s first year in office as his country’s head of state.

But even though India and Russia like to portray their relationship as an example of a friendship that has remained steady amid shifting geopolitical currents, their ties haven’t been immune to pressures from other nations.

Since 2000, New Delhi and Moscow have had in place a system of annual summits: The Indian prime minister would visit Russia one year, and the Russian president would pay a return visit to India the following year.

That tradition, however, was broken in 2022, the year of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine. Modi was supposed to visit Russia for the summit, but the conclave was put off.

In 2023, Putin skipped a visit to India for the G20 summit in New Delhi. At the time, Putin was rarely travelling abroad, largely because of an International Criminal Court (ICC) warrant against him related to the Ukraine war. India is not a member of the ICC – and so it would have been safe for Putin to attend, but Western members of the G20 made it clear that their leaders would be uncomfortable sharing the room with the Russian president.

Finally, in 2024, the annual summit resumed, with Modi visiting Russia. And now, Putin will land in New Delhi after four years.

Trade analysts and political experts expect Putin to push for India to buy more Russian missile systems and fighter jets, in a bid to boost defence ties and explore more areas to expand trade, including pharmaceuticals, machinery and agricultural products.

The summit “offers an opportunity for both sides to reaffirm their special relationship amidst intense pressure on India from [US] President [Donald] Trump with punitive tariffs,” Praveen Donthi, a senior analyst for India at Crisis Group, a US-based think tank, told Al Jazeera.

Putin, analysts said, will be seeking optical dividends from the summit.

“President Putin can send a very strong message to his own people, and also to the international community, that Russia is not isolated in the world,” said Rajan Kumar, a professor of international studies at Jawaharlal Nehru University in New Delhi.

“Russia is being welcomed by a democracy when Putin faces pressure for the war in Ukraine,” Kumar told Al Jazeera.

But visuals aside, a key driver of the India-Russia relationship – oil trade – is now at risk. And that, along with the shadow of the man responsible for the disruption, will be hovering over talks, said experts.

India became the second-largest buyer of Russian crude after Moscow invaded Ukraine in 2022 – an increase of a staggering 2,250 percent in imports, as Russia’s share in its imports went from 1 percent to 40 percent.

The US at the time quietly encouraged India to buy more Russian oil, New Delhi says. The West was stopping purchases of Russian crude, and a complete global ban on that oil would have shrunk global supplies, raising prices. India, by increasing its uptake of Russian oil, helped stabilise the global market.

But as Trump, in his second term, has looked for levers to use to pressure Moscow and Kyiv to end the war, he has targeted India for buying Russian oil. After initially imposing 25 percent tariffs on Indian goods, Trump doubled that to 50 percent as a penalty for Russian crude purchases.

For months after that, India continued importing Russian oil and defended what it called its “strategic autonomy”.

However, in October, Trump imposed sanctions on Russia’s two biggest oil firms – Rosneft and Lukoil – and threatened sanctions against firms of other countries that trade with them.

Reliance, India’s largest private oil refiner – and the biggest buyer of Russian oil in India – has since said that it will no longer export petroleum products that use Russian crude.

Indian imports of Russian crude are expected to fall to a three-year low now. Meanwhile, India recently signed a deal to dramatically ramp up its import of gas from the US.

In the defence sector too, the US has been pressuring India to buy more from it and less from Russia.

“New Delhi is wary of upsetting Washington regarding its defence deals with Moscow, but that’s not going to deter it from making important deals,” said Donthi, the analyst at Crisis Group. “India hopes to blunt US criticism by making similar deals with it, some of which are already under way.”

But Trump’s pressure risks hurting goodwill for the US in India.

Kanwal Sibal, former Indian foreign secretary and an ex-ambassador to Russia, said Trump and the US were employing “double standards”.

“Trump can roll out a red carpet for Putin in Alaska. Why should India not build on its ties with Russia then?” he added, referring to the Trump-Putin summit in August.

While the bilateral energy ties between India and Russia face several barriers, their defence ties are steadier.

Russia remains India’s largest defence supplier, accounting for roughly 36 percent of arms imports, and more than 60 percent of India’s existing arsenal.

Import numbers have come down from 72 percent in 2010, as India attempts to boost domestic production and also buy more from the US and European nations. But experts say that Russia’s position as India’s pre-eminent defence partner will likely remain unchallenged for several years.

The Russian S-400 missile defence system was central to India’s air defences during its four-day air war with Pakistan in May. India’s air force chief, Marshal AP Singh, said that “the S-400 was a game changer” for India.

New Delhi is now looking to buy additional S-400 air defence systems. Russia, meanwhile, wants to also sell India its Su-57 fifth-generation stealth fighter jets. “The SU-57 is the best plane in the world,” said Dmitry Peskov, Putin’s press secretary, ahead of the summit. “And it will be on the agenda.”

India-Russia trade has undergone a major shift since 2022, ballooning from a modest $10bn to a record nearly $69bn this year, primarily fuelled by New Delhi’s appetite for discounted Russian crude oil.

However, these numbers remain lopsided: Indian exports, largely pharmaceuticals and machinery, stand at roughly $5bn, resulting in a widening $64bn trade deficit. And Russia’s exports to India have been dominated by oil over the past three years. With trade now expected to fall, so will overall numbers, caution experts. The India-Russia goal of reaching $100bn in trade by 2030 appears distant.

Instead, analysts told Al Jazeera, the two countries now appear to be betting on labour migration as a driver of people-to-people and economic ties.

According to the estimates of the Russian Ministry of Labour, by 2030, the country is expected to see a shortfall of 3.1 million workers. Indian workers could fill that gap.

“Russia is opening up its labour market for India and looking to change its traditional supplier of labour from Central Asian countries to India,” said Kumar, the professor of international studies. “This kind of migration can have a positive impact on India-Russia relations.”

That won’t change the fundamental tension that undergirds India’s ties with Russia: New Delhi’s keenness to not damage relations with the US in the process.

As India simultaneously negotiates trade deals with the US, the European Union and the Eurasian Economic Union, an economic bloc led by Russia at the moment, New Delhi is walking a fine line “where it risks antagonising either of them, who are all important economic trade partners,” said Kumar.

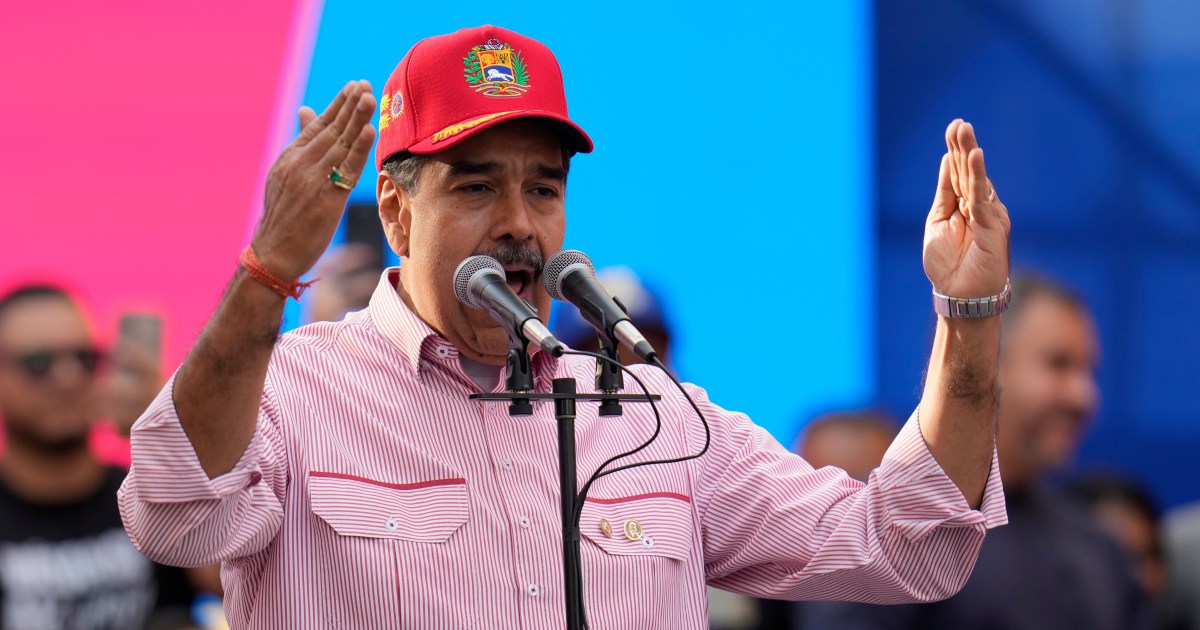

In the midst of a US military expansion that has sparked fears of war, Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro confirmed speaking with US President Donald Trump via phone late last month.

Maduro told the state-run television station on Wednesday that he had arranged for a “microphone diplomacy” when he called Trump and that he had a conversation about it about ten days ago.

list of 4 itemsend of list

In a statement referring to the late Venezuelan leader Hugo Chavez, under whom he was foreign minister, Maduro said, “During my six years as foreign minister, I learned diplomatic prudence, and then, in these years as president, I value prudence.

“I don’t like diplomacy with microphones; when sensitive issues arise, they must be handled quietly until they are resolved”!

Maduro claimed that he was encouraged by the suggestion that the call would lead to “respectful dialogue” and that his nation would always seek peace.

Maduro said he would not discuss further with Trump because he supported “prudence” and “respect.”

According to him, “With the blessing of God and Our Lord Jesus Christ, everything will work out well for Venezuela’s peace, independence, dignity, and future.”

Trump said he had spoken with the Venezuelan leader by phone in the midst of the most severe diplomatic dispute between Washington and Caracas in a long time, and Maduro made these remarks on Sunday.

Trump and Maduro spoke once more about their conversation on Wednesday, but they didn’t go into specifics.

Trump said at a press conference at the White House, “I spoke to him briefly, just told him a few things, and we’ll see what happens with that.”

Venezuela sends us people they shouldn’t be sending, but Venezuela does so with drugs.

As part of an escalating pressure campaign against Maduro, Trump has deployed the largest aircraft carrier in the world to the Caribbean, blown up alleged drug-smuggling vessels, threatened to launch strikes on Venezuelan soil, and threatened to do so in the name of a global conspiracy.

The Trump administration has used its military campaign to combat drug trafficking.

Venezuela accounts for only a small portion of the world’s cocaine supply, but it provided 10 to 13 percent of the projected cocaine production in 2020, according to a US government estimate.

Maduro claims that Trump fabricated allegations that he intended to overthrow his government and seize Venezuela’s vast oil reserves.

Maduro said his country wished for peace, but only with the words “sovereignty, equality, and freedom” attached, in a defiant address to a rally in Caracas on Monday.