When I read a report from an internationally renowned NGO called Oxfam International, which revealed that just four of Africa’s richest billionaires have a combined wealth of $57.4 billion, I was overcome by a profound sense of desperation and disappointment on July 9, 2025. This figure, according to Oxfam, exceeds the total wealth of roughly 750 million Africans, or roughly half of the continent’s population.

Additionally, the top 5 percent of Africans now have nearly $4 trillion in assets, which is more than twice the remaining 95%’s combined assets.

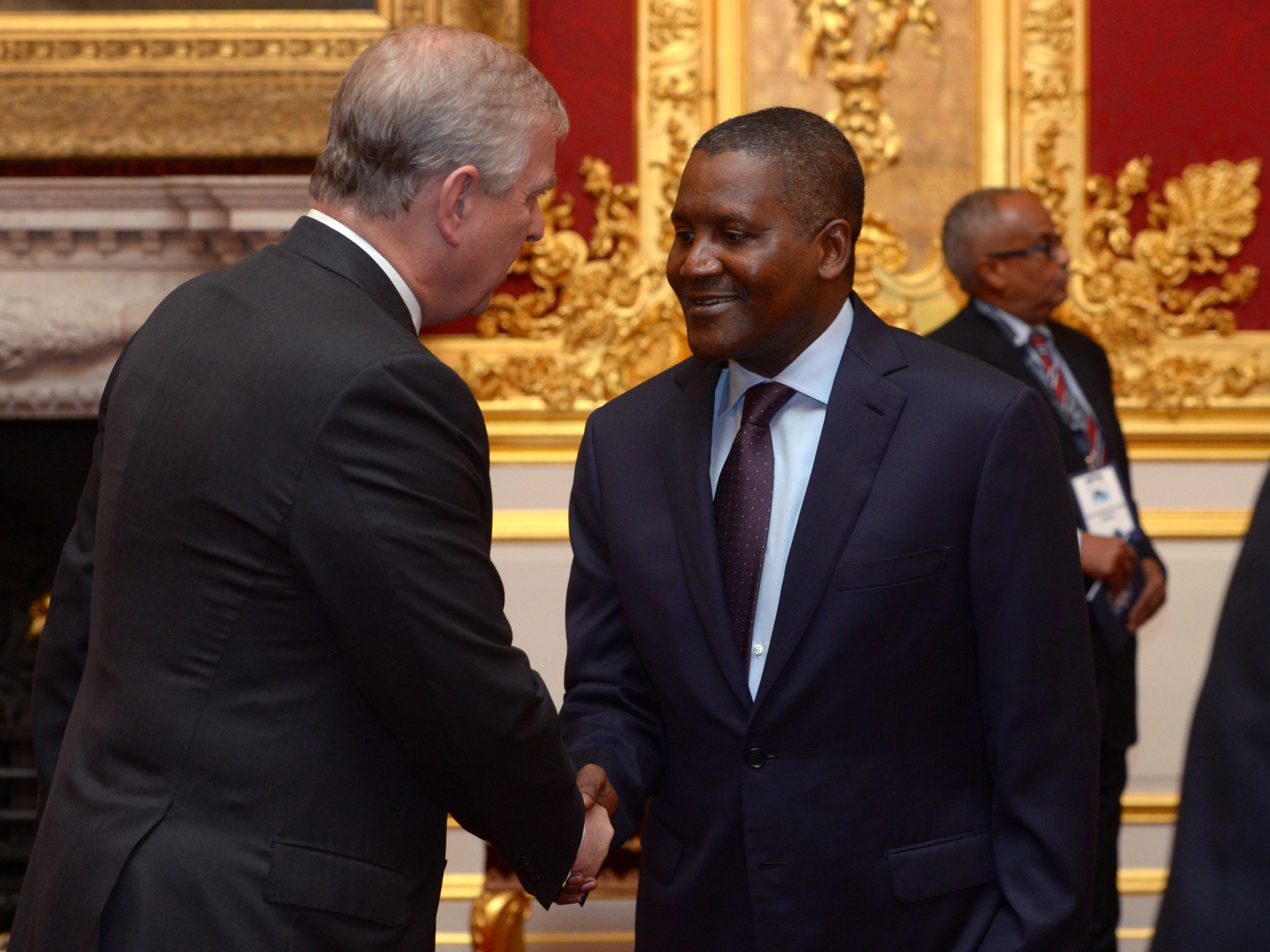

The report names the four wealthiest people on the continent in the report, Africa’s Inequality Crisis and the Rise of the Superrich. Nigerian Aliko Dangote, whose estimated net worth is $23.3 billion, is at the top. Johann Rupert and his South African family, who have about $14.2 billion in assets, come next. Nicky Oppenheimer and his family, both of whom are from South Africa, have a fortune worth $10.2 billion. Egyptian Nassef Sawiris’ net worth is estimated to be $ 9.4 billion.

I fall into the bottom 95 percent, the unsightly groups of people who have worked for modest incomes while aspire to socioeconomic transformation. There were no billionaires in Africa at the start of the 21st century in 2000. 23 billionaires, primarily men, make up the majority of the population, whose combined wealth has increased by 56 percent over the past five years, totaling an astonishing $ 112 billion.

No two countries, including Nigeria and South Africa, better illustrate the stark wealth disparity and oligarchic dominance of Africa today, and Aliko Dangote is the most prominent business leader to point out the rise of crony capitalism.

Why, please.

Dangote was merely a multimillionaire businessman with ambition 25 years ago. Then, on February 23, 1999, he contributed significantly to the presidential campaign of General Olusegun Obasanjo. His business trajectory was impacted by that seemingly benign investment.

Under the Backward Integration Policy (BIP), the Obasanjo administration began a comprehensive privatization of state-owned businesses in an effort to liberalize the economy, attract private investment, and promote domestic entrepreneurship. In 2000, Dangote Cement, the country’s largest cement producer, bought both Obajana Cement and Benue Cement, laying the groundwork for Dangote Cement, the latter two now dominate the industry.

On profits of approximately 1 trillion Nigerian naira (roughly $6 billion at 2015 exchange rates), Dangote Cement reportedly paid an effective tax rate of less than 1%. In 2007, Dangote became the country’s richest entrepreneur, becoming a billionaire as a result of the company’s rapid expansion.

The debate over quid pro quo tactics between Dangote and the Obasanjo administration has since become a well-known, albeit contentious, element of Nigerian politics and business.

Critics claim that the BIP has stifled competition and promoted monopolistic practices in important industries like sugar and cement, disproportionately favoring politically connected elites, including Dangote, at the expense of smaller businesses and regular Nigerians.

Nigeria has world-class human capital and is abundantly resourced. However, despite the most recent population estimates of about 227 million, more than 112 million people, or nearly half of the country’s population, live in poverty. The country’s five wealthiest individuals, who rule over industries like oil and gas, banking, telecommunications, and real estate, have a combined wealth of $ 29.9 billion.

Nigeria’s dysfunctional system has fostered oligarchic patterns and allowed the “big five” to grow. In its post-apartheid era, South Africa, the most industrialized nation in Africa, faces similar but distinct challenges.

The African National Congress (ANC) introduced the Broad-Based BEE Initiatives (BBBEE) and Black Economic Empowerment (BEE) on April 27, 1994, after apartheid ended. These policies sought to increase employment, promote effective Black economic participation, and promote fairer income distribution.

However, the ANC itself acknowledged over time that the majority of Black South Africans, particularly Black women, did not gain from these affirmative action initiatives in significant ways. Economic conditions have only marginally improved in the 31 years since apartheid. Despite the recent emergence of a few Black business leaders, they continue to excel in a system designed to favor a select few.

Patrice Motsepe, a mining magnate and one of Africa’s richest people, is one such example, with an estimated net worth of $3 billion. Supporters claim that his wealth is a direct result of the post-apartheid economic transformation, but critics, including economist Moeletsi Mbeki, refute this claim. In a system plagued by elite capture, Motsepe, who is also President Cyril Ramaphosa’s brother-in-law, is a hardly recognisable exception.

South Africa’s official unemployment rate was 32.9 percent by April 2025, which equaled the number of people actively looking for work. The overall rate, which included discouraged job seekers, increased to 43.1 percent. More than half of South Africa’s population, or 34.3 million people, were living in poverty around the same time.

The Oppenheimer family’s wealth is growing as a result of its deep historical connections to South Africa’s colonial past, which are evident in the enormous fortune it has in diamond mining. According to a study by the Harvard Growth Lab that was published in November 2023, the economy is defined by stagnation and exclusion, and the current strategies fail to achieve inclusion and empowerment in practice.

Unsurprisingly, ANC insiders and aligned business elites have been the most notable beneficiaries of the BEE initiatives, including Bridgette Radebe, sister of Motsepe, and Jeff Radebe’s wife, a staunch supporter of the ANC.

This particular elite group is in stark contrast to the regular South Africans who are the intended beneficiaries of the BEE. Instead, these individuals are grappling with persistent cuts to the budgets for education and health, as well as widespread corruption, poor service delivery, and lingering effects of oligarchic state control.

This pattern is prevalent in Nigeria. In a vibrant African economy, Dangote’s enormous wealth should at least be considered to be the pinnacle of success. He instead exemplifies Africa’s most powerful and wealthy oligarch, showing how close proximity to political power can lead to contentious paths to fortune. Regrettably, almost every African nation has its own Motsepe or Dangote, which are both influential and prevent fair and equitable economic development.

Political connections preclude innovation and advancement, which is a marked departure from free market ideals. This distortion results in social inequality, economic inefficiency, and corruption. By allowing private interests to exert excessive influence over public policy, it also weakens democratic norms.

According to a 2015 study from Columbia University, politically connected oligarchs’ wealth has a significant negative impact on economic growth, whereas unconnected billionaires’ wealth has little impact. This finding suggests that limiting the political power of politically connected elites would lead to slower economic growth in African countries.

It is time for significant reform right now.

High-net-worth individuals are subject to a wealth tax, and it must be used to fund essential services in underdeveloped countries.

A modest tax increase, which would be equivalent to 2.29 percent of Africa’s gross domestic product, would help close funding gaps in education and access to electricity, say Oxfam.

To reduce poverty and promote happiness, African nations must adopt economic policies that are more inclusive.

We are 95% of the neglected and disenfranchised population.

Source: Aljazeera

Leave a Reply