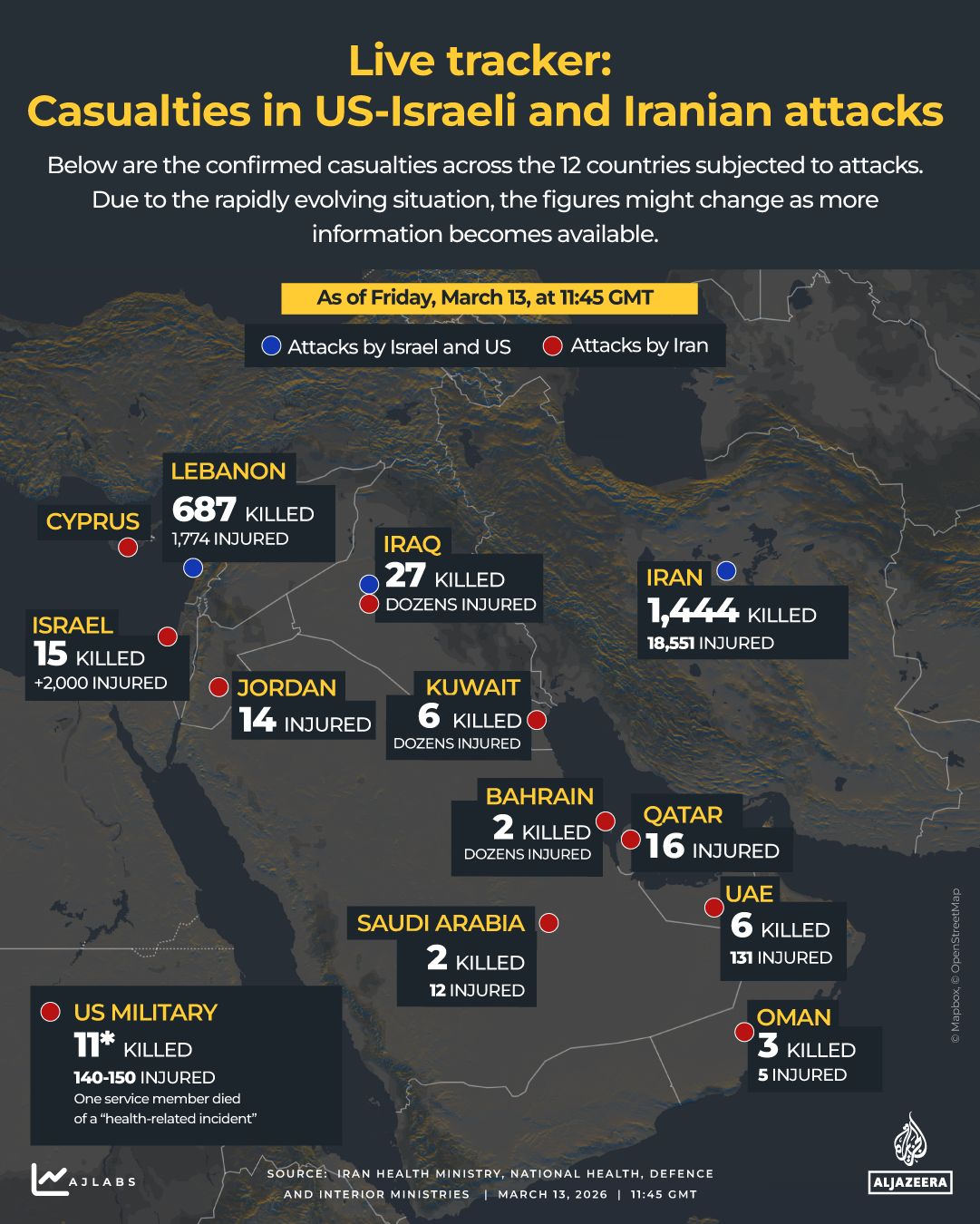

An Israeli strike on a health centre in southern Lebanon has killed 12 medical workers, the Lebanese Ministry of Public Health said, as the Israeli devastating assault continued amid a wider regional war launched by the United States and Israel on Iran 15 days ago.

The attack late on Friday occurred in the village of Burj Qalaouiyah in the Bint Jbeil District, and killed doctors, paramedics and nurses who were on duty, Lebanon’s Health Ministry said.

Recommended Stories

list of 4 itemsend of list

The carnage echoed Israel’s constant targeting of medics and hospitals that decimated Gaza’s healthcare system during its genocidal war on the Palestinian enclave, and which contravenes international humanitarian law.

Israeli attacks have so far killed 18 paramedics among 773 people reported killed in Lebanon since fighting between Hezbollah and Israel reignited on March 2, after a US-Israeli assault on Iran began on February 28, with the conflict now embroiling much of the region.

According to Al Jazeera’s Heidi Pett, reporting from Beirut, the toll of medics was preliminary as rescue teams continued searching for missing people.

“You can see how deadly some of these individual air strikes have been, not just across the south, but of course, we are seeing air strikes hitting across the capital, Beirut,” said Pett.

Lebanon’s Health Ministry said this was the second attack on the health sector within hours, after another Israeli strike on the southern village of Souaneh killed two paramedics and wounded five when it hit a paramedic centre.

The ministry condemned the attack and denounced what it called continued violence against health workers.

At least four people were also killed in an Israeli air raid on Taamir Haret Saida in the country’s south, the Lebanese News Agency (NNA) said.

Meanwhile, Hezbollah overnight claimed it fired suicide drones against Israeli troops in the northern town of Ya’ara inside Israel.

It was the 24th military operation announced by the group on Friday.

The Lebanese armed group also said it launched rocket attacks against Israeli soldiers in southern Lebanon, one in the town of Kfar Kila and the other in the city of Khiam.

Late on Friday, Hezbollah leader Naim Qassem said his group is ready for a “long confrontation” with Israel as the war continues.

“This is an existential battle, not a limited or simple battle,” he said.

Damage in Israel from Iranian ‘cluster missiles’

Meanwhile, Iran’s retaliatory attacks against Israel continued.

Rocket and missile attacks early on Saturday hit the Upper Galilee region of northern Israel, Channel 12 reported.

The news outlet said a “limited number of launches” were either “intercepted” or exploded in open areas.

A post on X from Israel’s public broadcaster Kan featured several vehicles damaged in the attacks.

Alarms were raised for suspected rocket and missile fire in Manara, Margaliot, Kfar Giladi, Misgav Am, Tel Hai, Metula and Kfar Yuval throughout the early morning on Saturday.

“A lot of the damage that we are being told about at the moment seems to be coming from these cluster missiles that Iran has been launching pretty much consistently for the last week at least, and they scatter over a large area,” said Al Jazeera’s Rory Challands, reporting from Amman, Jordan.