EXPLAINER

Eight contenders will fight for a spot in the semifinals of the ICC Men’s T20 World Cup 2026 as the second stage of the tournament gets under way on Saturday.

Pakistan became the last team to book their place in the Super Eight with a win over Namibia on Wednesday, while former champions Australia’s early exit was the biggest shock of the group stage.

Recommended Stories

list of 4 itemsend of list

Here’s what you need to know about the Super Eight:

Which teams have qualified for the T20 World Cup Super Eight?

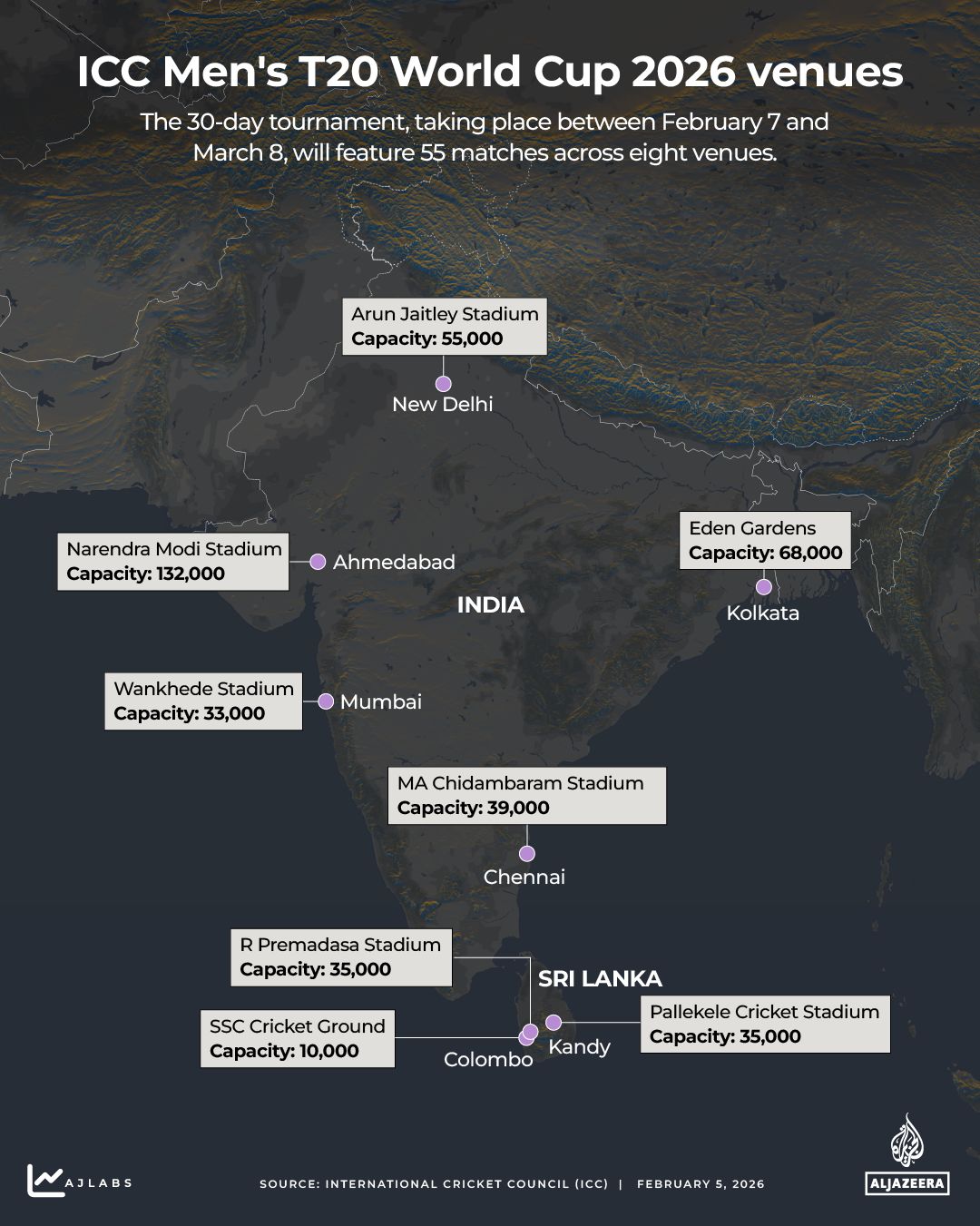

The eight sides have been divided into two groups of four teams, with India and Sri Lanka hosting a group each.

Group 1:

- India

- South Africa

- West Indies

- Zimbabwe

Group 2:

- England

- New Zealand

- Pakistan

- Sri Lanka

Will teams carry over their points and net run rates in the Super Eight?

Neither their points nor their net run rates will be carried over, giving each side a chance to start with a clean slate.

How do the Super Eight groups work?

Every team will play the other three teams once, and the top two teams at the end of the round of matches will proceed to the semifinals.

As in the group stage, a win in the Super Eight will earn two points and a loss will earn none.

If a match is tied at the end of each team’s 20 overs, a super over will be played until a result is determined.

What happens if it rains in a Super Eight match?

In case of poor weather, for a match to be considered completed, each team must play at least five overs each.

If the match is abandoned due to rain, both teams will walk away with a point apiece.

What’s the full match schedule of the Super Eight stage?

Saturday, February 21

Pakistan vs New Zealand at 7pm (13:30 GMT) – R Premadasa Stadium, Colombo

Sunday, February 22

Sri Lanka vs England at 3pm (09:30 GMT) – Pallekele International Cricket Stadium, Kandy

India vs South Africa at 7pm (13:30 GMT) – Narendra Modi Stadium, Ahmedabad

Monday, February 23

Zimbabwe vs West Indies at 7pm (13:30 GMT) – Wankhede Stadium, Mumbai

Tuesday, February 24

England vs Pakistan at 7pm (13:30 GMT) – Pallekele International Cricket Stadium, Kandy

Wednesday, February 25

New Zealand vs Sri Lanka at 7pm (13:30 GMT) – R Premadasa Stadium, Colombo

Thursday, February 26

West Indies vs South Africa 3pm (09:30 GMT) – Narendra Modi Stadium, Ahmedabad

India vs Zimbabwe at 7pm (13:30 GMT) – MA Chidambaram Stadium, Chennai

Friday, February 27

England vs New Zealand at 7pm (13:30 GMT) – R Premadasa Stadium, Colombo

Saturday, February 28

Sri Lanka vs Pakistan at 7pm (13:30 GMT) – Pallekele International Cricket Stadium, Kandy

Sunday, March 1

Zimbabwe vs South Africa at 3pm (09:30 GMT) – Arun Jaitley Stadium, New Delhi

India vs West Indies at 7pm (13:30 GMT) – Eden Gardens, Kolkata