For decades, the “alternative homeland” – the notion that Jordan should become the Palestinian state – was dismissed in Amman’s diplomatic circles as a distant nightmare or a conspiracy theory.

Today, under the shadow of a far-right Israeli government and a devastating genocidal war in Gaza, that nightmare has become an operational reality.

The alarm in the Hashemite Kingdom reached a fever pitch on Sunday, following the Israeli cabinet’s approval of measures to register vast swaths of the occupied West Bank as “state land” under the Israeli Ministry of Justice. The move, described by Israeli Finance Minister Bezalel Smotrich as a “settlement revolution”, effectively bypasses the military administration that has governed the occupied territory since 1967, treating it instead as sovereign Israeli soil.

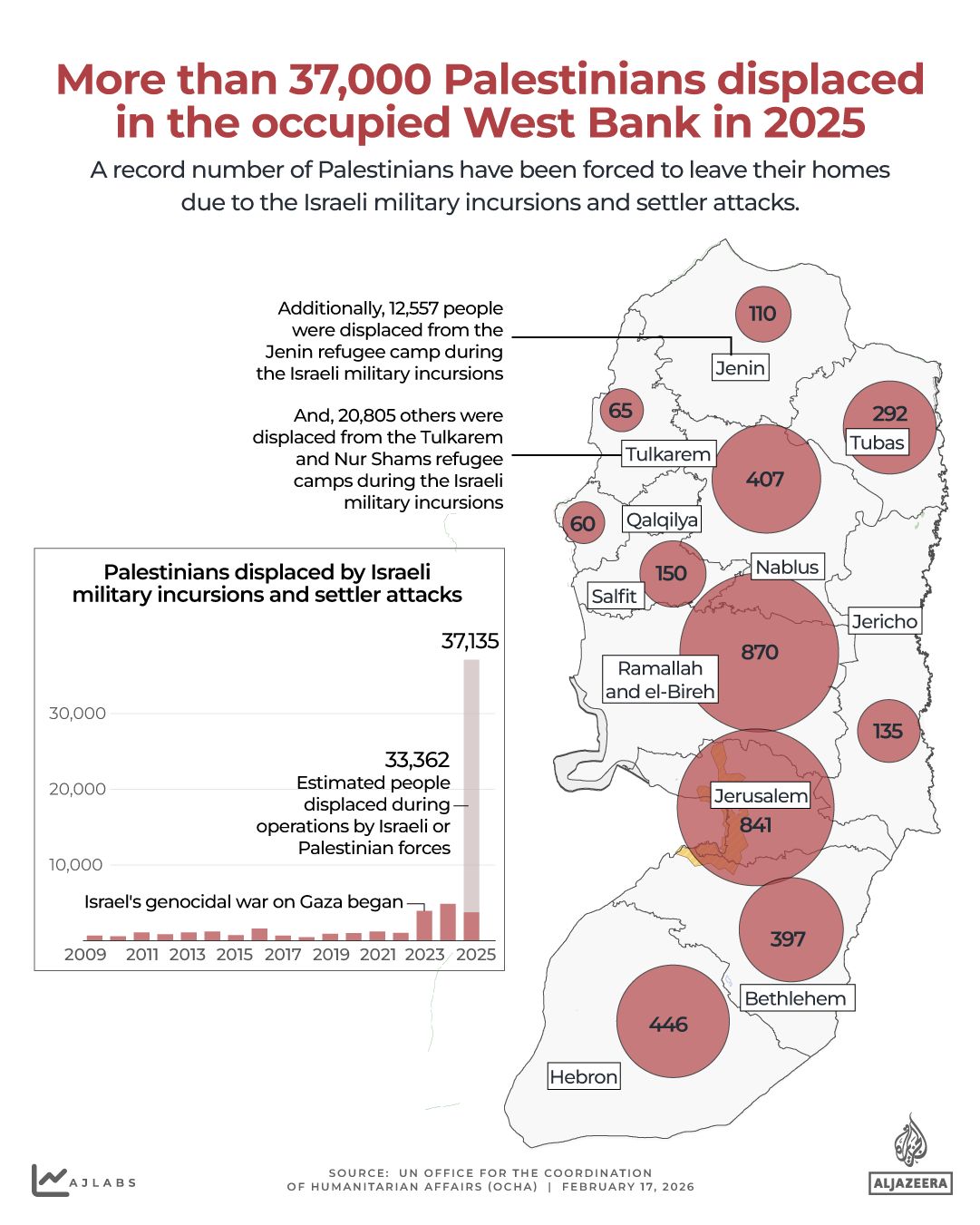

For Jordan, this bureaucratic annexation is the final signal that the status quo is dead. With the Israeli military’s “Iron Wall” operation crushing refugee camps in Jenin and Tulkarem, Jordan’s political and military establishment is no longer asking if a forced transfer is coming, but how to stop it.

“The transfer is no longer a threat; it is moving to execution,” Mamdouh al-Abbadi, Jordan’s former deputy prime minister, told Al Jazeera. “We are seeing the practical application … The alternative homeland is something that is coming; after this West Bank, the enemy will move to the East Bank, to Jordan.”

The ‘silent transfer’

The fear in Amman is not just about military invasion, but about a “soft transfer”, making life in the West Bank unliveable to force a gradual exodus towards Jordan.

Sunday’s decision to transfer land registration authority to the Israeli Justice Ministry is viewed in Jordan as a critical step in this process. By erasing the Jordanian and Ottoman land registries that have protected Palestinian property rights for a century, Israel is clearing the legal path for massive settlement expansion.

Al-Abbadi, a veteran voice in Jordanian politics, pointed to symbolic but dangerous shifts in Israeli military nomenclature.

“There is a new brigade in the Israeli army, named the Gilead Brigade,” al-Abbadi noted. “What is Gilead? Gilead is a mountainous region near the capital, Amman. This means the Israelis are proceeding with their strategic practices from the Nile to the Euphrates.”

He argued that the 1994 Wadi Araba Treaty is effectively null and void in the eyes of the current Israeli leadership.

“Smotrich’s ideology is not just the view of one person; it has become the doctrine of the state,” al-Abbadi said, warning that the Israeli consensus has shifted permanently. “They are the ones who killed the Wadi Araba treaty before it was even born … If we do not wake up, the strategy will be ‘either us or them’. There is no third option.”

A ‘second army’ of tribes

As diplomatic avenues narrow, questions are turning to Jordan’s military options. The Jordan Valley, a long strip of fertile land separating the two banks, is now the front line of what Jordanian strategists call an “existential defence”.

Major-General (retired) Mamoun Abu Nowar, a military expert, warned that Israel’s actions amount to an “undeclared war” on the kingdom. He suggested that if the displacement pressure continues, Jordan must be ready to take drastic measures.

“Jordan could declare the Jordan Valley a closed military zone to prevent displacement,” Abu Nowar told Al Jazeera. “This could lead to conflict and ignite the region.”

While acknowledging the disparity in military capabilities, he dismissed the idea that Israel could easily overrun Jordan, citing the kingdom’s unique social fabric.

“The Jordanian interior, with its tribes and clans … this is a second army,” Abu Nowar said. “Every village and every governorate will be a defensive line for Jordan … Israel will not succeed in this confrontation.”

However, he cautioned that the situation is volatile. With the West Bank potentially exploding into a religious conflict, he warned of a “regional earthquake” if red lines are crossed. “Our army is professional and ready for all scenarios, including military confrontation,” he added. “We cannot leave it like this.”

The collapse of the US guarantee

Compounding Jordan’s anxiety is a deep sense of abandonment by its oldest ally: the United States. For decades, the “Jordanian option” —the stability of the Hashemite Kingdom — was a cornerstone of US policy.

But Oraib al-Rantawi, director of the Al-Quds Center for Political Studies, argued that this “strategic wager” has collapsed.

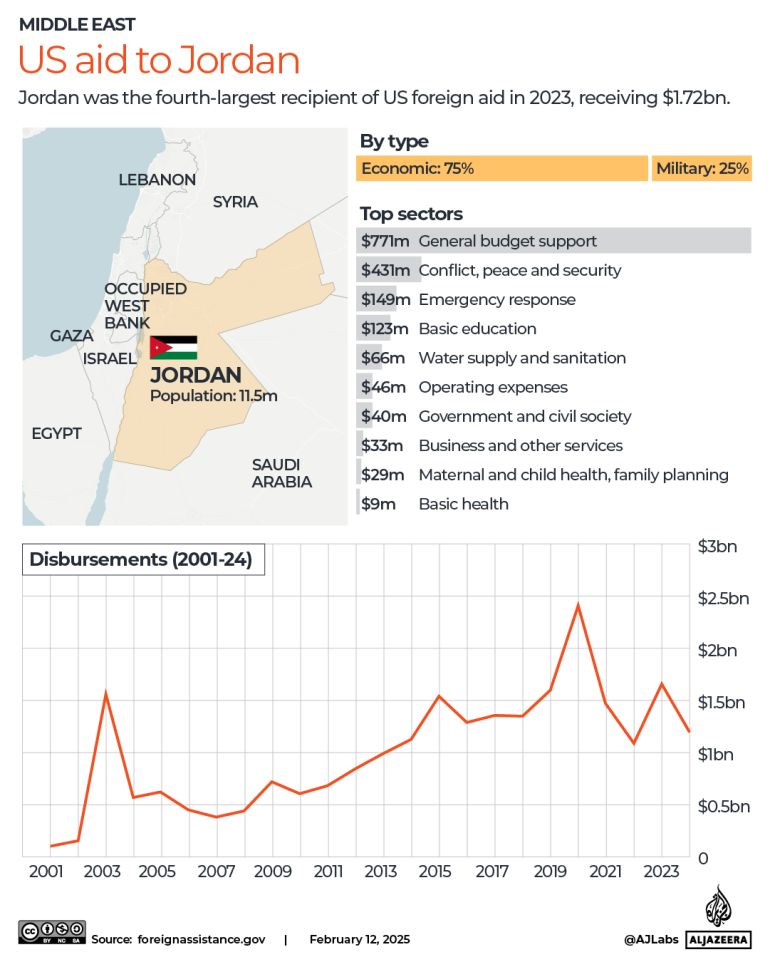

“The bet on Washington … has faltered, if not collapsed,” al-Rantawi told Al Jazeera. He pointed to a “paradigm shift” that began during US President Donald Trump’s first term, which saw Washington move its regional anchor from Amman and Cairo to the Gulf capitals, “dazzled by the shine of money and investments”.

Al-Rantawi noted that even under the Biden administration, and now with the return of Trump, the US has shown a willingness to sacrifice Jordanian interests for Israel.

“When put to the test — choosing between two allies — Washington will inevitably choose Israel without hesitation,” al-Rantawi said.

He described Jordan’s position as precarious, trapped in a dependency loop. “Jordan is between two fires: the fire of [US] aid on one hand, and the fire of the threat … the existential Israeli threat to the entity and identity,” he said.

General Abu Nowar echoed this scepticism regarding US protection, questioning whether Jordan’s status as a key non-NATO ally means anything in practice. “Will they apply Article 5 of NATO to us?” he asked. “This gives a lack of credibility to the Americans.”

Facing this isolation, voices in Amman are calling for a radical overhaul of Jordan’s alliances. The kingdom has traditionally maintained a cold peace with the Palestinian Authority (PA) in Ramallah while shunning Hamas and other resistance factions, a policy al-Rantawi believes has been a strategic error.

“Jordan shot its diplomacy in the foot,” al-Rantawi explained, by insisting on an exclusive relationship with the weakened PA in Ramallah.

He contrasted Jordan’s position with that of Qatar, Egypt, and Turkiye, which maintained ties with the Palestinian group Hamas and thus retained leverage. “Cairo, Doha, and Ankara kept ties with Hamas, which strengthened their presence even with the US,” he said. “Jordan gave up this role voluntarily … or due to miscalculation.”

Al-Rantawi suggested this reluctance stems from internal fears of empowering the Muslim Brotherhood within Jordan, but the cost has been a loss of regional influence just when Amman needs it most.

Preparing for the worst

The consensus among the elite is that the time for “diplomatic warnings” is over. The language in Amman has shifted to mobilisation and survival.

In early February, the kingdom officially resumed its compulsory military service programme, known as “Flag Service”, ending a 35-year hiatus. The Jordanian armed forces stated the move aims to “develop combat capabilities to keep pace with modern warfare methods” amid complex regional conditions.

Al-Abbadi went further, calling for universal conscription to ensure total readiness. “We ask the state for compulsory conscription; everyone in Jordan must be able to bear arms,” he said.

He also urged cultural mobilisation. “We must teach our children at least the Hebrew language, because he who knows the language of a people is safe from their evil.”

Calling for strict monitoring of the King Hussein (Allenby) Bridge crossing, he added: “If there is a slow, camouflaged transfer … we must close the bridges immediately and without hesitation.”

As the Israeli Justice Ministry begins rewriting the land deeds of the West Bank, erasing Palestinian ownership in ledgers just as their homes are erased on the ground, Jordan faces its most precarious moment since 1967. The buffer is gone, and the kingdom finds itself standing alone in the path of the storm.