Islamabad, Pakistan – On Sunday, Nepal’s then-Prime Minister KP Sharma Oli mocked youth protesters, who were planning a major agitation the following day in the capital, Kathmandu, against corruption and nepotism.

By calling themselves the “Gen Z”, the protesters seemed to believe they could demand whatever they wanted, he said.

Recommended Stories

list of 4 itemsend of list

Less than 48 hours later, Oli was an ex-PM, and the Gen Z protest movement he had spoken dismissively of was discussing who should lead Nepal. That was after police firing on protesters on Monday killed at least 19 people, further inflaming passions. On Tuesday, protesters set fire to the parliament building and homes of several prominent politicians, as members of Oli’s cabinet quit and pressure mounted on the PM himself – ultimately leading to his resignation. The combined death toll from clashes on Monday and Tuesday has now reached 31.

Those dramatic events have turned the Himalayan nation into the latest cauldron of political change, after similar youth-led movements in Sri Lanka‚ in 2022, and Bangladesh, in 2024, also led to the overthrow of governments in those South Asian nations.

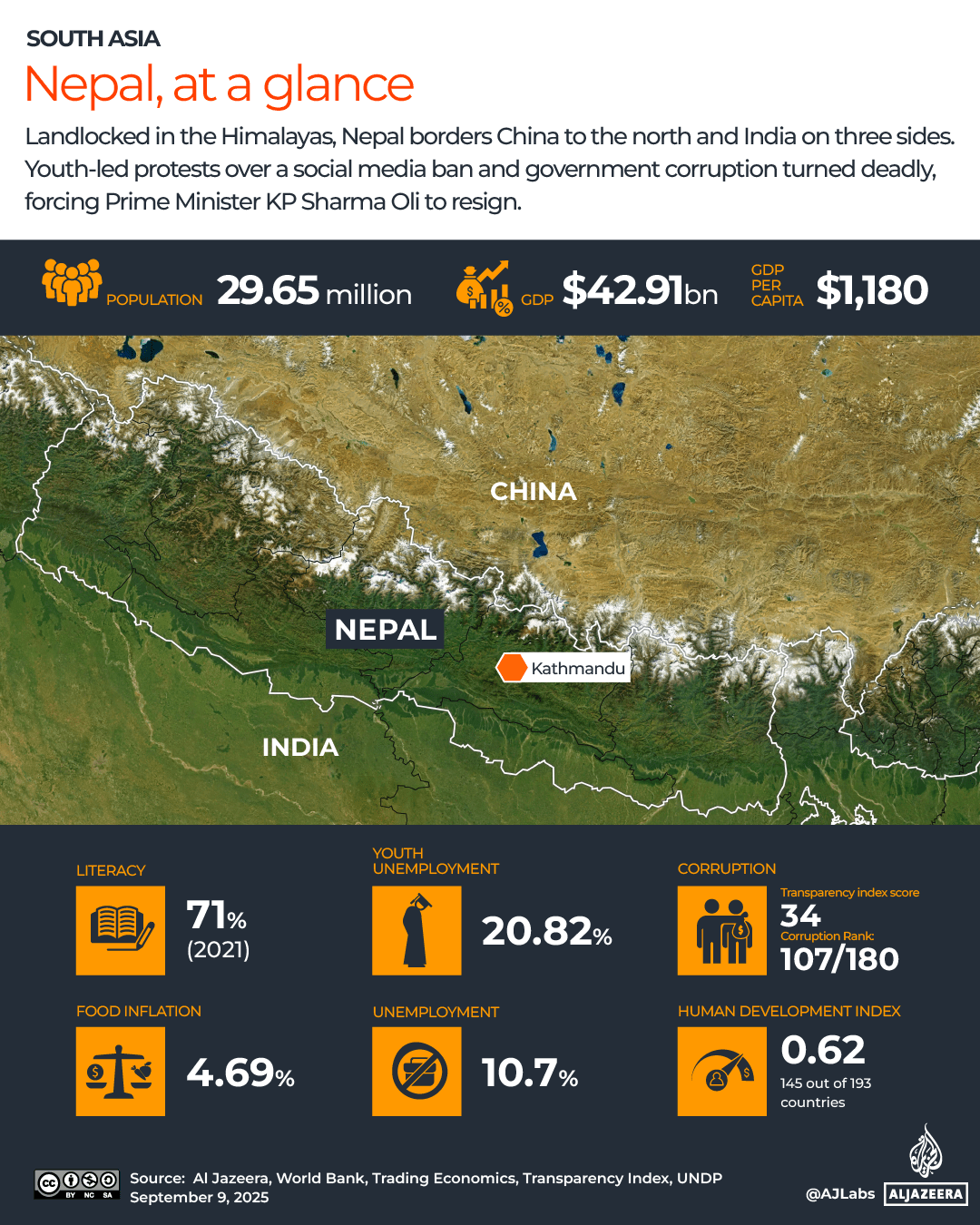

Experts say that Nepal’s political churn has consequences not just for the nation of 30 million people, but for the broader region and the world, rooted in the country’s own tumultuous political history and its legacy of balancing ties between India, China and Pakistan.

Here’s what happened and why it matters to the world:

What’s happening in Nepal?

On September 8, tens of thousands of young people came out to protest corruption and nepotism. A government ban on social media platforms only aggravated their anger.

After some protesters broke through barricades and entered the parliament complex, security forces fired live bullets, tear gas shells and water cannons at them. At least 19 people died, angering youth across the country.

New protests – far more violent – erupted on Tuesday. Politicians’ homes and offices of political parties were broken into and set on fire. The building that housed Kantipur Publications, Nepal’s biggest media house, was also torched.

By afternoon, Oli had announced his resignation, but the protesters, who have described their agitation as a “Gen Z movement”, are now demanding the dissolution of parliament, new elections, an interim government they help choose until then, and the prosecution of those who ordered the firing on September 8.

The army has taken over the streets, and a curfew is in place in Kathmandu.

But this was not Nepal’s first encounter with mass student unrest. The country’s modern political history is filled with student movements, palace interventions and cycles of violence, including a decade-long civil war.

From Rana rule to the Panchayat era

Several educated Nepalis had participated in undivided India’s freedom struggle against the British, and inspired by the subcontinent’s independence from colonial rule in 1947, became a part of a larger movement calling for the end of direct rule by Nepal’s Rana monarchy.

In 1951, opposition to the Ranas – including from educated sections of the elite – culminated in what was the country’s first modern revolution. The Ranas were forced to accept indirect rule through a tripartite agreement. Nepal’s King Tribhuvan, who had fled to India in the protests, returned. A government was formed with members of the Rana clan and the Nepali Congress (NC) – the main political party at the time.

Then, in 1959, the country held its first general election, with the NC’s Bishweshwar Prasad Koirala becoming prime minister. But just a year later, King Mahendra Bir Bikram dismissed the Koirala government after its popular land reforms angered sections of the country’s ruling elite. Instead, the king imposed what became known as the “panchayat” system, a party-less order that governed Nepal for nearly three decades, with the monarch at its helm.

With political activity curtailed, student protests became one of the few outlets for dissent. Campus agitations over political and educational reforms occurred through the 1970s and 1980s.

The sustained political protest over the years eventually brought down the panchayat system in 1990 and reopened the door to parliamentary politics.

The armed rebellion and the emergence of a republic

Between 1996 and 2006, the Communist Party of Nepal (Maoist) waged a rebel-led war aimed at toppling the monarchy for democratic rule. The conflict killed more than 10,000 people.

In 2006, protests involving political parties, civil society and students forced the monarch, King Gyanendra, to cede power. The movement paved the way for the abolition of the monarchy and, in 2008, the declaration of Nepal as a democratic republic.

Since then, eight men from the three main parties – the Communist Party of Nepal (Unified Marxist-Leninist) (CPN-UML), the Communist Party of Nepal (Maoist Centre) (CPN-MC) and the Nepali Congress (NC) – have led the country 14 times between them. Oli, who resigned on September 9, was serving his fourth term.

Observers say that though the Oli government’s recent social media ban was a lightning rod for protesters, the Gen Z movement is built on underlying grievances that have simmered for years.

Rajneesh Bhandari, an investigative journalist based in Kathmandu, says the demonstrations reflected “frustration” against the rulers for their “corruption, acts of nepotism, and their bad governance”.

“This shows that the Nepalese youth held resentment against the rulers who did not pay heed to their demands, or communicated with them, and continued to act in an arrogant manner,” he told Al Jazeera.

Ashirwad Tripathy, a civil and digital rights activist in Kathmandu, also emphasised that the protests were not an overnight eruption.

“The abuse of authority and corruption of the leaders of the several political parties have led to this situation. There has been long-simmering discontent and dissatisfaction against the older generation of the three main political parties, who only played musical chairs with the prime minister’s seat,” Tripathy told Al Jazeera.

Geography, neighbours and power politics

But what happens in Nepal matters well beyond the borders of the landlocked country that sits on the southern slopes of the Himalayas and is home to eight of the world’s 14 highest peaks, including Mount Everest.

Stretching roughly 885km (550 miles) east to west and about 193km (120 miles) north to south, it lies between two regional giants: China to the north and India to the south, east and west.

Though historically close to India, Nepal’s foreign alignments have shifted with domestic politics. Oli was widely seen as leaning towards Beijing, and his removal has prompted speculation about a recalibration of influence in Kathmandu.

Lokranjan Parajauli, a social scientist who has written extensively on social movements and politics, suggested the next ruler is likely to be an “independent” figure not aligned with any party.

“It is not quite clear who that new person will be, but it will be someone whom the army can trust or rely upon,” Parajauli told Al Jazeera.

Some analysts point to Sushila Karki, the former chief justice, as a possible interim choice.

“She is the most acceptable candidate, and she has a high chance of leading the next government, but no decision has been made,” Tripathy said, adding that Karki’s political and diplomatic allegiances are unclear.

Others believe that the mayor of Kathmandu, Balendra Shah, a 35-year-old rapper musician who has been heading the city since 2022, could be the other option.

However, a longtime human rights activist in Kathmandu, speaking on condition of anonymity, said regardless of the identity of the new leader, both India and China will seek stability and a government that “respects their interests”.

“Neither neighbour wants to see the other exercise too much influence in Nepal,” the activist told Al Jazeera.

Tripathy emphasised Nepal’s historical balancing act.

“Nepal has always had friendly ties with both its neighbours, China and India. Culturally, we are closer to India in the southern part, while the northern part has cultural similarities with China. But our motto has always been to maintain a balanced relationship between both countries, and we will continue the same notion,” he said.

Regional calculus

Ali Hassan, a South Asia specialist at UK-based Healix, a risk management company, argued that Oli’s fall could serve as a setback for Beijing in Kathmandu and a potential opening for New Delhi.

Sections of Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) have also been aligned with the pro-monarchist movement in Nepal, which argues that the Himalayan nation needs the Ranas back in power. The former monarch, Gyanendra, received a huge public reception in Kathmandu earlier this year, pointing to the continuing support for the former rulers among sections of Nepali society. If the pro-monarchy movement gains from the current politicial crisis in Nepal, that might benefit the BJP, Hassan said.

But he added that the Gen Z protesters who removed Oli do not appear to favour a return of Gyanendra.

Meanwhile, Pakistan will also be watching developments in Nepal closely, say analysts.

Compared with India and China, Nepal’s relations with Pakistan have historically been cordial but limited in strategic significance.

Still, Nepal’s rulers have used ties with Pakistan, at times, to remind India of their own regional options. In 1960, the Indian government under Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru criticised King Mahendra’s dismissal of the Koirala government. A year later, the Nepali monarch visited Pakistan, and then, in 1963, hosted Pakistani President Ayub Khan.

More recently, at the height of India-Pakistan tensions in May, after gunmen had killed 26 civilians in Indian-administered Kashmir, Nepal hosted a delegation from Pakistan’s National Defence University, leading to raised eyebrows in New Delhi, which has long viewed Oli as too close to Beijing – Pakistan’s closest ally – for comfort.

With Pakistan having seen its share of political chaos in recent years, particularly after the removal of Prime Minister Imran Khan through a parliamentary vote of no confidence in 2022, analysts say Nepal’s crisis might have raised concerns among Pakistan’s ruling elite, too.

“Pakistani elites must be wondering how secure their grip on power is, given they are often accused of charges similar to what Bangladeshi, Sri Lankan and Nepali protesters said of their leaders, that the government is indifferent to all but themselves and is highly authoritarian,” London-based Hassan said.

But the Kathmandu-based human rights activist who requested anonymity said that from Nepal’s perspective, Pakistan would likely not be a priority for the next leader – whoever it is.

Source: Aljazeera

Leave a Reply