Oualata is one of a quartet of fortified towns, or ksour, whose historical significance as trading and religious centers earned it the title “World Heritage.” They still contain remnants of a rich medieval past today.

The earthen facades of Oualata are punctuated by acacia wood doors with traditional designs that local women have painted on the walls. Family libraries safeguard incredibly valuable collections of cultural and literary heritage that have been passed down through generations.

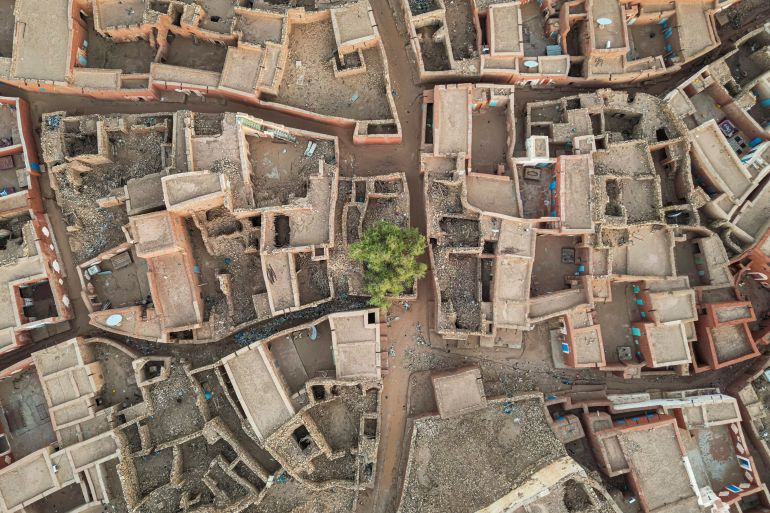

Oualata is acutely vulnerable to the harsh Sahara environment because of its close proximity to the Malian border. The town’s historical walls have become strewn with stone and holes as a result of particularly severe recent rains, which have caused piles of stone and seasonal downpours.

Standing next to her crumbling childhood home, which is now her inheritance from her grandparents, Khady said, “Many houses have collapsed because of the rains.”

Oualata’s decline has only been accelerated by depopulation.

Sidiya, a member of a national foundation dedicated to protecting the country’s ancient towns, claimed that “the houses became ruins because their owners left them.”

Oualata’s population has remained stagnant for generations as residents relocate and leave their historic structures foreclosed. The traditional structures, which are covered in red mud-brick known as banco, were designed to withstand the desert’s climate but still need maintenance after the rainy season.

Only about one-third of the Old Town’s buildings are actually inhabited, leaving the majority of it to be abandoned.

Desertification is “our biggest issue,” according to the statement. “Oualata is covered in sand everywhere,” Sidiya said.

About 80% of the country is affected by desertification, which is a “adverse state of land degradation” caused by “climate change (and) inappropriate operating practices,” according to the Mauritania’s Ministry of Environment.

Even Oualata’s mosque was submerged in sand by the 1980s. Bechir Barick, a geography lecturer at Nouakchott University, said that “people were praying on top of the mosque” rather than inside.

Oualata is still home to remnants of its past as a major gateway to the trans-Saharan caravan routes and a renowned center of Islamic learning despite the relentless sand and wind.

Mohamed Ben Baty, the town’s imam, is the author of nearly a millennium of scholarship and is a member of a renowned line of Quranic scholars. 223 manuscripts, the oldest of which date back to the 14th century, are housed in the family library he controls.

He hurriedly opened a cupboard in a cramped, cluttered room to display its priceless, centuries-old documents, which are fragile and have survived unheilingly.

Ben Baty pointed to pages that had water stains and were once very poorly maintained and vulnerable to destruction as he approached the books, which were then stored in plastic sleeves. In the past, books were kept in trunks, he said, recalling a roof collapse eight years ago during the rainy season when the water seeped in and could ruin them.

More than 2, 000 books were restored and preserved digitally in Oualata thanks to funding from Spain in the 1990s. However, a small number of enthusiasts like Ben Baty, who doesn’t reside in Oualata year-round, are now relying on their dedication to keeping these documents preserved.

Because the library contains a lot of valuable documentation for researchers in various fields, including languages, the Quran, history, and astronomy, he said, “the library needs a qualified expert to ensure its management and sustainability.”

The nearest town, Oualata, is a two-hour drive across rugged terrain, and the island’s isolation prevents tourism development. The town’s location in a region where many nations advise against traveling, citing the threat of rebel violence, makes things even more difficult.

Three decades ago, Sidiya acknowledges that the planting of trees around Oualata was insufficient in response to efforts to combat the encroaching desert.

Oualata and the three other historic towns that were reunited in 1996 on the UNESCO World Heritage List have been the subject of a number of initiatives. One of the four towns hosts a festival each year to raise money for restoration, investment, and to encourage more people to stay.

Source: Aljazeera

Leave a Reply