The seventh election in Uganda since 1986, when Yoweri Museveni took office, is in January 2026. Repression is rising as in the weeks leading up to previous polls. However, it has now spread beyond Uganda’s own borders.

Opposition politician Kizza Besigye and his aide Obeid Lutale were kidnapped on November 16, 2024, in Nairobi, Kenya. They were detained on security charges in Kampala, Uganda, and appeared in court four days later. The two civilians faced military justice when they were sent to Uganda in flagrant violation of international law that forbids extraordinary rendition and due process.

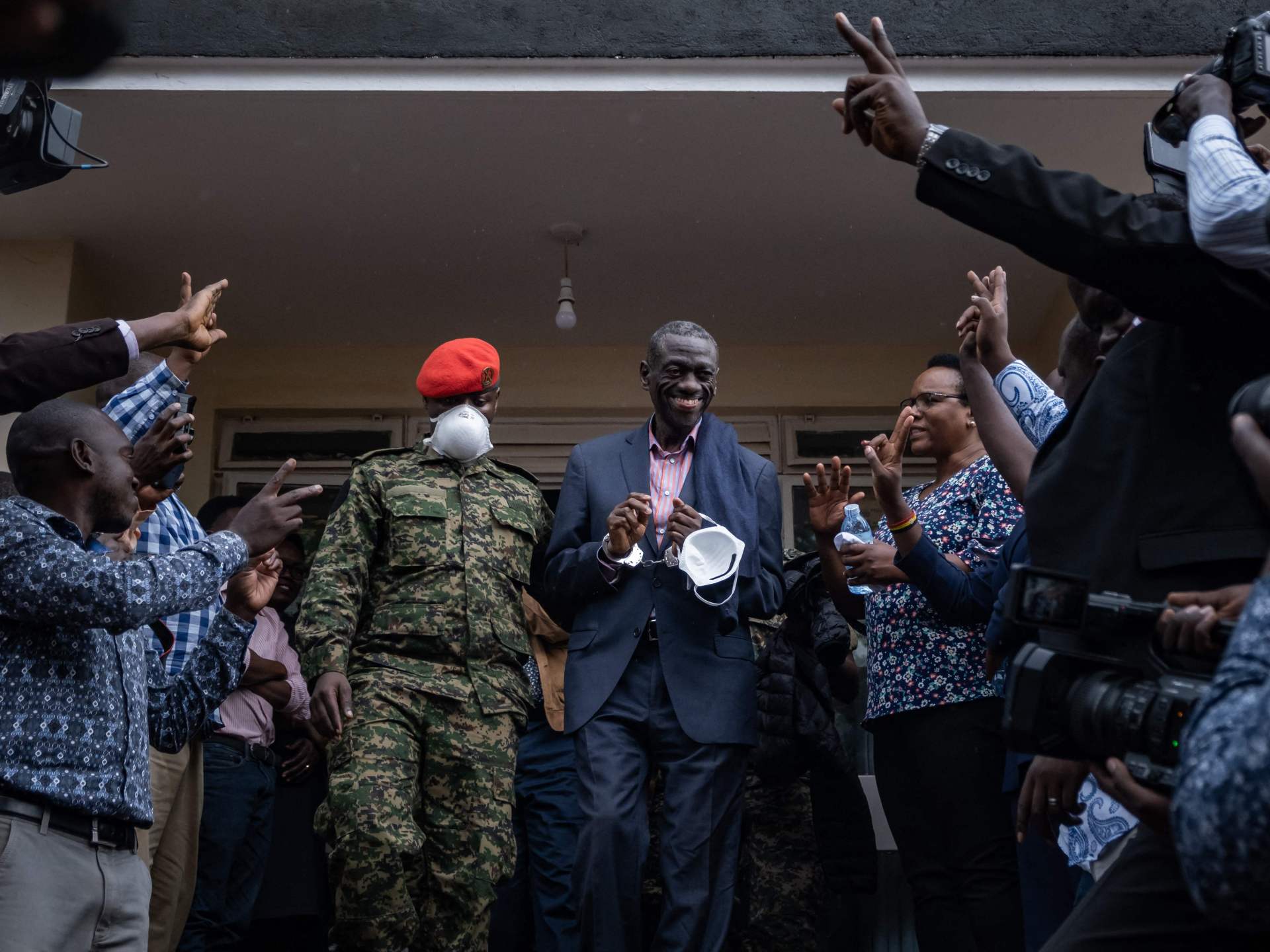

Besigye and Lutale attracted a 40-person defense team led by Kenya’s former justice minister, Martha Karua, outraged by this militarisation of justice.

The state’s practices have done the opposite if the goal was to silence opposing voices. These trials have sparked a national dialogue on human rights and the role of the military, far from deterring other people from speaking up.

General Muhoozi Kainerugaba, Museveni’s son, is the country’s Chief of Defence Forces (CDF), and he has frequently made comments about Besigye’s case on X. Despite current law prohibiting serving military officers from engaging in partisan politics, Kainerugaba is widely perceived as a potential successor to his aging father.

The Supreme Court of Uganda has been putting off a decision in a case brought by former parliamentarian Michael Kabaziguruka challenging the prosecution of civilians in military courts since 2016. Kababiguruka, who was accused of treason, claimed that his military tribunal trial violated the law’s fair trial standards. He claimed that military law applied to him as a civilian. This was given new life by the case of Besigye and Lutale.

The Supreme Court ruled on January 31, 2025, that civilian trials involving civilians in military courts are unconstitutional, and it is required that all civil trial cases involving civilians must be adjourned and sent to regular courts as soon as possible.

President Museveni and his son have vowed to use military courts for civilian trials despite this ruling. Besigye began a 10-day hunger strike to protest delays in turning his case over to a regular court. Before the 2026 elections, the case has now served as a litmus test for Uganda’s military justice system.

Not just opposition politicians face military justice, Besigye and Lutale. The National Unity Platform (NUP), led by Robert Kyagulanyi and known as Bobi Wine, have had their convictions over a number of offences by military courts. Despite their distinct differences, the NUP’s signature red berets and other party attire were reported to have resembled military uniforms. In addition, a number of lesser-known political activists are facing charges in military courts.

Since 2002, more than 1, 000 civilians have been charged with crimes like murder and armed robbery in Uganda’s military courts.

For context, the state changed the UPDF Act to allow the military to bring civil rights cases before military courts in 2005. These amendments occurred during the military’s investigation of civilians detained between 2001 and 2004, including Kizza Besigye, which was no accident.

Military trials of civilians violate regional and international standards. They open the door to a flurry of human rights violations, including forced confessions, shady procedures, unfair trials, and executions.

The 2001 Principles and Guidelines for Fair Trial and Legal Assistance in Africa and Article 7 of the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights are both violated by military courts in which countries. The region’s leading human rights organization, the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights, has long condemned their usage in Uganda.

Opposition to military justice has not just been expressed informally. Following the Supreme Court’s ruling, religious leaders expressed concern about Besigye’s continued detention, as did Anita Among, the speaker of Uganda’s Parliament and a member of the ruling National Resistance Movement (NRM), who said, “Injustice to anyone equals injustice to everyone. Dr. Besigye is currently receiving treatment, and anyone else will experience it tomorrow.

Besigye and Lutale were moved to a civilian court on February 21 following the court’s ruling and widespread outcry. Besigye called a stop to his hunger strike. They are still being held, as is their attorney. However, their illegal release, which was just started with illegality, still has flaws. Scores of more civilians have their cases pending in military courts despite the transfer of their case, with little hope that they will be transferred to civilian courts.

For this reason, 11 organizations, including Amnesty Kenya, the Pan-African Lawyers Union, the Law Society of Kenya, the Kenya Human Rights Commission, and the Kenya Medical Practitioners, Pharmacists, and Dentists Union (KMPDU), request their immediate release.

The military courts are now a tool in President Museveni’s arsenal to silence dissent as elections near in Uganda. Uganda should take note of the Supreme Court’s ruling, but for the time being, military justice is also being tried.

Source: Aljazeera

Leave a Reply