On August 20, Islamabad, Pakistan- , India announced that its intermediate-range ballistic missile, Agni-V, had been successfully tested fired from a range in Odisha on its eastern Bay of Bengal coast.

The Agni-V, meaning “fire” in Sanskrit, is 17.5 metres long, weighs 50, 000kg, and can carry more than 1, 000kg of nuclear or conventional payload. It is one of the world’s fastest ballistic missiles, capable of traveling more than 5,000 kilometers at nearly 30 000 km per hour at hypersonic speeds of nearly 30 000 km/h.

According to experts, the Agni test took place exactly a week after Pakistan announced the formation of a new Army Rocket Force Command (ARFC) to address deficiencies in its defensive posture exposed by India during the four-day conflict between the nuclear-armed neighbors in May.

But experts say the latest Indian test might be a message less for Pakistan and more for another neighbour that New Delhi is cautiously warming up to again: China.

Most of Asia, including parts of China’s northern regions, and parts of Europe are within reach thanks to the Agni’s range. The missile’s timing, according to analysts, was crucial even though this was its 10th test since 2012 and its first since March of last year.

It came just ahead of Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s trip to China for the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) summit, amid a thaw in ties – after years of tension over their disputed border – that has been accelerated by United States President Donald Trump’s tariff war against India. In response to tensions over New Delhi’s oil purchases from Russia, US tariffs on Indian goods increased to 50%  on Wednesday.

Despite this teasing, India continues to see China as its main threat in the region, according to experts, underscoring the complex relationship between the world’s two most populous countries. And it’s at China that India’s development of medium and long-range missiles is primarily aimed, they say.

India’s advantage with missiles over Pakistan

India admitted losing an unspecified number of fighter jets in the May skirmish with Pakistan, but it also caused significant damage to Pakistani military installations, particularly with its supersonic BrahMos cruise missiles.

The BrahMos, capable of carrying nuclear or conventional payloads of up to 300kg, has a range of about 500km. Its low altitude, terrain-hugging trajectory, and blistering speed make it difficult to intercept, making it relatively easy to penetrate Pakistani territory.

This context, according to many experts, demonstrates that Pakistan’s announcement of the ARFC is not directly connected to the Agni-V test. Instead, they say, the test was likely a signal to China. Before Modi met Chinese President Xi Jinping in Russia in October 2024, the two countries engaged in a deadly standoff along their disputed Himalayan border for four years following a deadly clash.

First time visiting China since 2018, Modi will make the trip to the SCO summit on Sunday. In the past, India has often felt betrayed by overtures to China, which, it claims, have frequently been followed by aggression from Beijing along their border.

According to Manpreet Sethi, a distinguished fellow at the New Delhi-based Center for Air Power Studies, “India’s requirement for a long-range, but not intercontinental, missile is dictated by its threat perception of China.”

A nuclear-capable ballistic missile with a range of 5, 000 kilometers is Agni-V, which India has developed as a tool for its nuclear deterrence against China. It has no relevance to Pakistan”, Sethi added.

The University at Albany’s assistant professor of political science, Christopher Clary, concurred.

The Agni-V’s main task would be to strike China, he told Al Jazeera, though Pakistan might be a useable country for it. “China’s east coast, where its most economically and politically important cities are situated, is hard to reach from India and requires long-range missiles”.

South Asian missile race

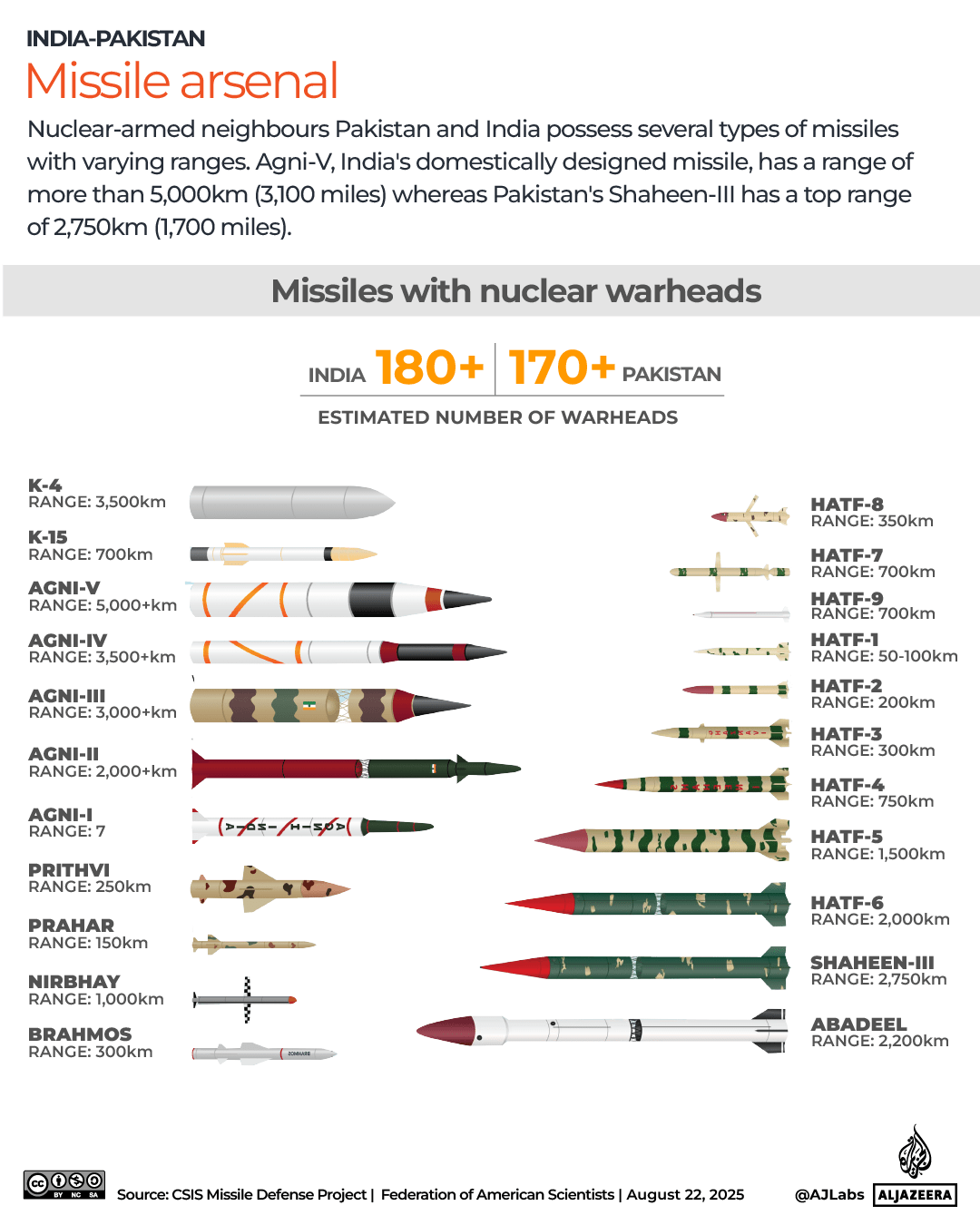

In recent years, India and Pakistan have steadily developed new missile systems with greater reach.

Before announcing the ARFC, Pakistan showcased the Fatah-4, a cruise missile with a 750km range and the capability to carry both conventional and nuclear warheads.

Meanwhile, India is working on Agni-VI, which is expected to have a range of more than 10,000 kilometers and support multiple independently targetable reentry vehicles (MIRVs), an ability that is already present in Agni-V.

MIRV-enabled missiles have a number of nuclear warheads that can strike specific targets, significantly increasing their destructive potential.

Mansoor Ahmed, an honorary lecturer at the Strategic and Defence Studies Centre, Australian National University, said India’s latest test demonstrates its growing intercontinental missile capabilities.

This test served as a technological demonstration of India’s developing submarine-launched ballistic missile (SLBM) capability, Ahmed said, adding that India was working on various Agni variants with multiple capabilities.

India will be able to deploy 200 to 300 warheads on its SSBN force alone over the next ten years, he added. SSBNs (ship, submersible, ballistic, nuclear) are nuclear-powered submarines designed to carry SLBMs armed with nuclear warheads. Two more SSBNs are currently being constructed in India, and two are already in use.

In contrast, there are no nuclear submarines or long-range missiles in Pakistan. Its longest-range operational ballistic missile, the Shaheen-III, has a range of 2, 750km.

The first ballistic missile capable of hitting anywhere in South Asia with MIRV technology, Ababeel, is the shortest-range, MIRV-enabled system ever deployed in any nuclear-armed state, according to Ahmed.

Former Pakistani army brigadier and expert on nuclear policy, Tughral Yamin, said missile ambitions reflect different priorities.

“Pakistan’s programme is entirely Indian-specific and defensive in nature, while India’s ambitions extend beyond the subcontinent. According to Yamin, the author of The Evolution of Nuclear Deterrence in South Asia, its long-range systems are designed to help it become a global power, especially in relation to China, and establish itself as a great power with effective deterrence against major powers.

However, some experts contend that India is not the only country that is involved in Pakistan’s missile development program.

Ashley J Tellis, the Tata Chair for Strategic Affairs at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace (CEIP), said that while “India wants to be able to range China and Pakistan”, Islamabad is building the capability to keep Israel – and even the US – in its range, in addition to India.

Tellis told Al Jazeera, “Both countries’ conventional missile force is designed to strike critical targets without putting manned strike aircraft in danger.”

US concerns about Pakistan’s ambitions, and a quiet acceptance of India’s rise

Pakistan’s missile programme came under intense spotlight in December last year when a senior White House official warned of Islamabad’s growing ambitions.

In a statement from Jon Finer, a member of the then-Biden administration, Finer referred to Pakistan’s “emerging threat” to the United States.

“If the trend continues, Pakistan will have the capability to strike targets well beyond South Asia, including in the United States”, Finer said during an event at the CEIP.

Tellis argued that Washington and its allies don’t consider India’s growing arsenal to be destabilizing.

Tellis cited the US’s arrest of Osama bin Laden in Pakistan in 2011 as an example of how Pakistan’s capabilities are unsettling because the country’s nuclear program had anti-Western overtones and sentiments that have since changed with the Abbottabad raid.

Ahmed, the Canberra-based academic, said India’s long-range missile development is openly supported by Western powers as part of the US-led Asia Pacific strategy.

“India has been viewed and encouraged to act as a net security provider by the US and the European powers.” Without signing the Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT), he claimed, the civil nuclear agreement between India and the US and the waiver by the Nuclear Suppliers Group (NSG) gave India de facto nuclear weapons.

The NPT is a Cold War-era treaty aimed at preventing the spread of nuclear weapons, promoting the peaceful use of nuclear energy and advancing the goal of nuclear disarmament. It formally recognizes only the United States, Russia, China, France, and Britain as nuclear weapons states.

India was able to engage in global nuclear trade despite not having signed the NPT, which elevated its status in the eyes of the NSG, a group of 48 countries that sell nuclear materials and technology.

Clary from the University of Albany, however, pointed out that unlike the Biden administration, the current Trump White House has not expressed any concerns about Pakistan’s missile programme – or about India’s Agni-V test.

Source: Aljazeera

Leave a Reply