The United Kingdom’s government is investing in spyware developed and tested on Palestinians in Gaza and the occupied West Bank despite its public criticism of Israeli action there.

In addition to the Corsight facial recognition technology used to track, trace and detain thousands of Palestinian civilians passing through checkpoints in Gaza and the West Bank, the UK government has disregarded its own public concerns over Israel’s war on Gaza and de facto annexation of the West Bank and has purchased spyware from at least two other Israeli-linked manufacturers: Cellebrite and BriefCam.

Recommended Stories

list of 4 itemsend of list

Cellebrite

Cellebrite is an Israeli company closely linked to that country’s military. It has developed software that can bypass passwords and security protocols on smartphones and computers and access data from them.

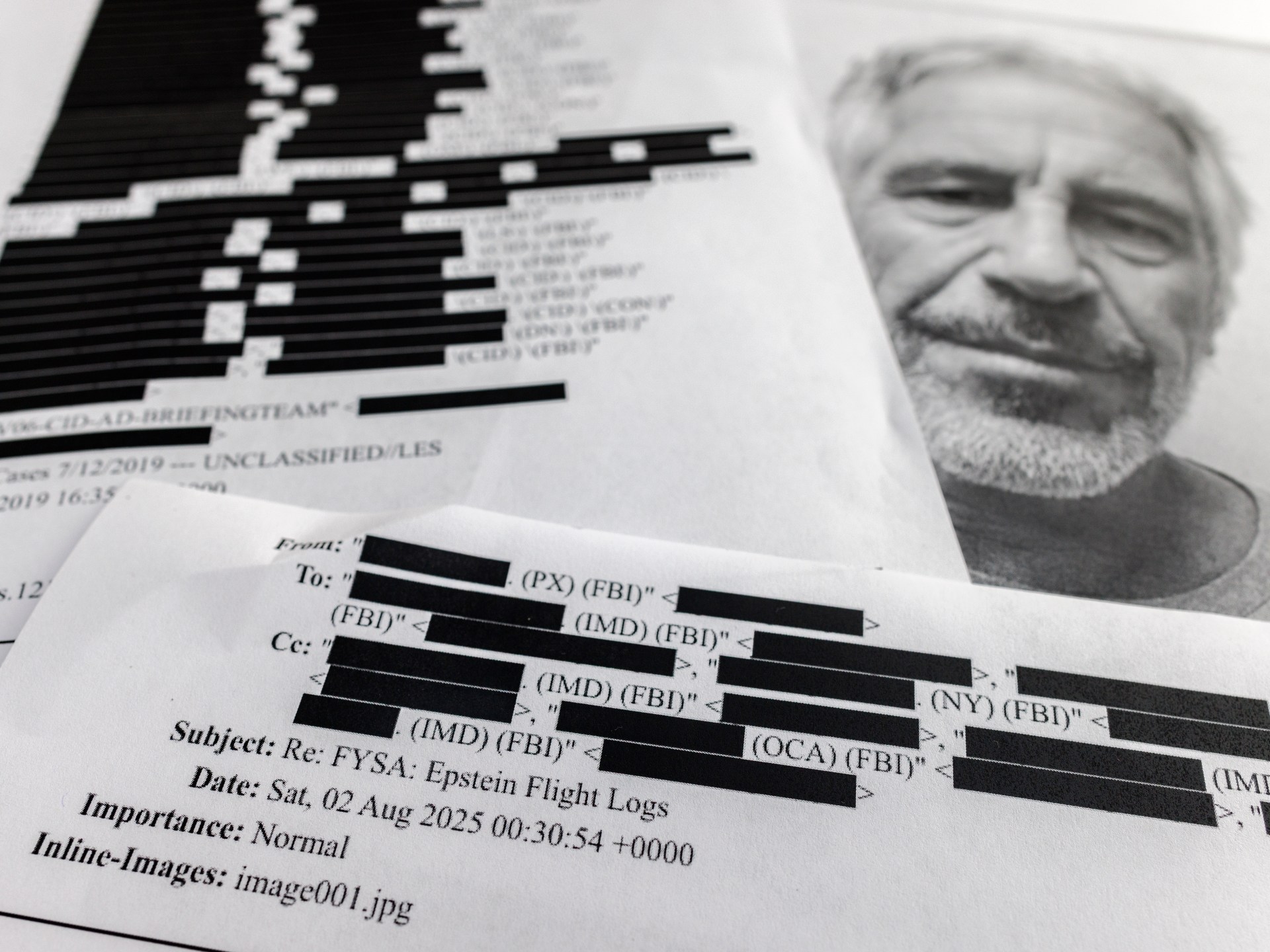

That software has been used extensively by the Israeli military on Palestinians across Gaza and the West Bank, including to harvest data from the phones of thousands of detained Palestinians, many of whom have been subjected to systematic torture, a report by the American Friends Service Committee said.

Cellebrite is also reported to have received support from the United States Department of Defense to work on technology designed to map underground tunnels in the Gaza Strip.

Despite its stated public concerns over Israeli action in Gaza and the West Bank, records show the UK has entered into several agreements to take advantage of the technology used by Israel in Palestinian territory.

According to public records, a number of UK police forces have purchased access to Cellebrite software, including the City of London Police, which renewed its one-year contract with the Israeli company for more than 95,000 pounds ($128,600) in June. Leicestershire Police also renewed its contract with the Israeli spyware company in March for 328,688 pounds ($445,300). The British Transport Police, the UK’s Serious Fraud Office, Kent and Essex police, and Northumbria Police have also entered into contracts with Cellebrite.

Inquiries from Al Jazeera to the UK Home Office, Home Secretary Shabana Mahmood and the UK Police’s commercial agent, Blue Light Services, have all gone unanswered.

However, while declining to comment on “specific customer relationships or contracts”, Victor Cooper, Cellebrite’s senior director of corporate communication, rejected the characterisation of the company’s activities as “hacking”, instead saying, “Cellebrite’s solutions are forensic tools used in legally sanctioned investigations and require physical possession of the device. They do not enable remote access.”

Rights groups have raised concerns over Cellebrite exporting its technology to hardline states worldwide, including Myanmar, Serbia and Belarus, where it has been used to extract information from the phones of opposition figures, journalists and activists.

BriefCam

The Israeli-founded company BriefCam, which was acquired by Canon in 2018 and then by the Danish company Milestone Systems last year, has been providing the UK’s Cumbria Police with surveillance software since at least 2022.

A further disclosure by Police Scotland in June confirms that Scotland’s police service is also considering using the service.

BriefCam was founded in 2007 by Shmuel Peleg, Gideon Ben-Zvi and Yaron Caspi based on technology developed at Israel’s Hebrew University.

The company provides video synopsis programmes to law enforcement agencies, governments and companies. Police forces and private firms can use BriefCam’s Protect & Insights platform to sift through and condense hours of CCTV and home-surveillance footage, making it easily searchable.

The system includes facial-recognition and licence-plate search tools and allows police to build “watch lists” of specific faces or vehicle plates.

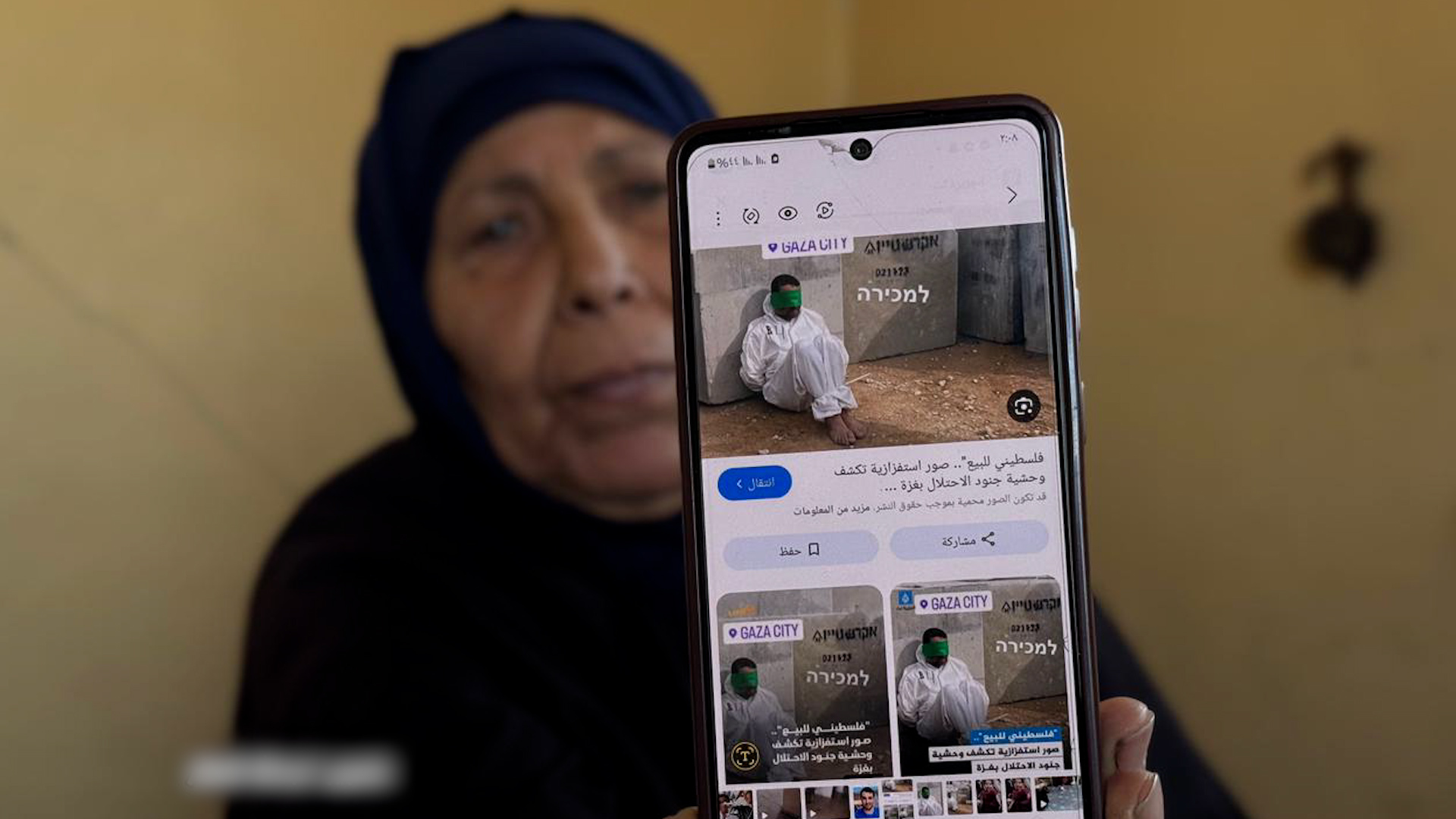

The technology has been used in East Jerusalem, Palestinian territory illegally occupied by Israel.

According to undated files accessed by the research centre Who Profits, a tender document published by the Israeli Ministry of Housing and Construction inviting companies to bid for maintenance contracts for 98 security systems within East Jerusalem specified that the successful bidder must be able to maintain BriefCam’s software. Israeli public records also show that in 2021, Israeli police committed to a contract valued at $1m for BriefCam’s video analysis systems.

A May 2023 report by the rights group Amnesty International documented how surveillance technology, such as that provided by BriefCam, was instrumental in maintaining Israel’s subjugation of Palestinians.

According to the report, the use of surveillance software is critical in maintaining the “continued domination and oppression of Palestinians … [w]ith a record of discriminatory and inhuman acts that maintain a system of apartheid”.

While not mentioning BriefCam by name, the report continued: “The Israeli authorities are able to use facial recognition software – in particular at checkpoints – to consolidate existing practices of discriminatory policing, segregation, and curbing freedom of movement, violating Palestinians’ basic rights.”

According to the company, the software can also filter footage by a wide range of characteristics, including gender, age group, clothing, movement patterns and time spent in a given location.

And that, despite the technology’s links to the oppression of Palestinians, is what makes it attractive to UK police forces.

Cumbria Police has said it does not currently use the facial recognition capabilities of BriefCam’s technology.

A spokesperson for Cumbria Police also clarified that the force has been using BriefCam for “several years” and, before introducing the technology, it had “consulted Cumbria’s independent Ethics and Integrity Panel and Strategic Independent Advisory Group”.

A request for a copy of those findings went unanswered.

Corsight

As previously reported by Al Jazeera, the Israeli company Corsight, through a subcontract with UK company Digital Barriers, has also been selected by the UK Home Office to play a key role in its expansion of facial recognition vans.

In March 2024, long before the UK government chose to include Corsight within its rollout of facial recognition technology, The New York Times revealed that misgivings over Corsight’s facial-recognition technology in Gaza had led to various members of the Israeli military voicing objections to its use by Unit 8200, Israel’s cyberintelligence branch.

The expansion of systems such as those marketed by Corsight, Cellebrite and BriefCam is part of a global trade in Israeli spyware, developed and refined through prolonged surveillance of Palestinians, that is now being exported worldwide.

Rights groups warned that techniques pioneered in Israel are being used by governments to target activists, journalists and political opponents as concerns deepen over the spread of unregulated cyberwarfare tools.