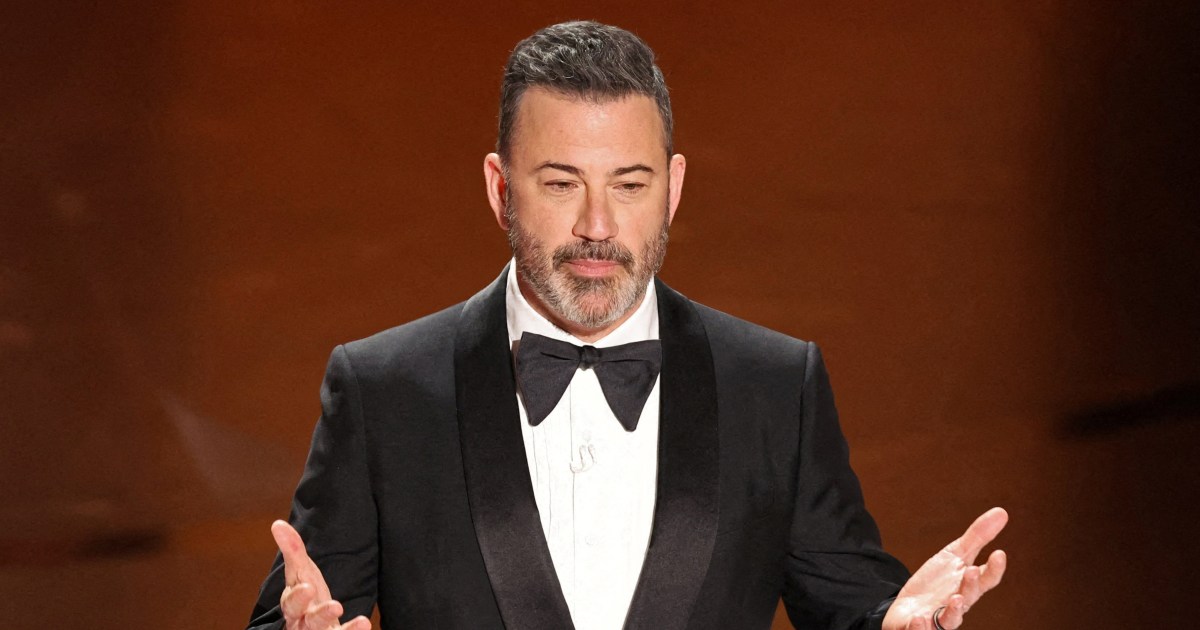

According to the host of the popular chat show’s host about the assassination of right-wing activist Charlie Kirk, ABC has made the announcement that it will indefinitely stop airing Jimmy Kimmel Live.

Due to Kimmel’s assertion that Tyler Robinson, the man charged with Kirk’s assassination last week, supports US President Donald Trump, the program would be “preempted indefinitely,” ABC-owned Walt Disney said on Wednesday.

Recommended Stories

list of 3 itemsend of list

In a monologue on his long-running late-night talk show on Monday, Kimmel said, “We hit some new lows over the weekend with the MAGA gang desperately trying to characterize this kid who murdered Charlie Kirk as anything other than one of them and trying to score political points from it.”

Nexstar Media, one of the nation’s largest local TV station owners, which includes at least 28 ABC affiliates, announced earlier that Kimmel’s remarks about the Kirk killing would cause the program to cease to air.

Andrew Alford, president of Nexstar Media, described Kimmel’s comments as “offensive and insensitive at a crucial time in our national political discourse.”

We don’t think they reflect the diverse viewpoints, beliefs, or values of the neighborhood communities where we are located, he said.

Questions remain regarding a potential motive despite the fact that Utah’s prosecutors have officially charged Robinson with killing Charlie Kirk and have said they will seek the death penalty.

The Federal Communications Commission (FCC), an independent US government TV, radio, and internet regulator, on Wednesday condemned Kimmel’s comments.

Carr also appeared to threaten ABC affiliate licenses as a result of the presenter’s remarks in an interview with right-wing YouTuber Benny Johnson.

Carr said, “What people don’t understand is that the broadcasters have a license granted by us at the FCC, and that license requires them to operate in the public interest.”

Carr specifically instructed ABC affiliates to “push back” on Jimmy Kimmel Live’s broadcasting because they “risiko license revocation” due to a “pattern of news distortion.”

Heidi Zhou-Castro of Al Jazeera noted that Kimmel is well-known in the US and has received more than 20 airtime from his talk show.

According to Zhou-Castro, “What he said on Monday was that he suggested Charlie Kirk’s suspected shooter was a pro-Trump Republican,” Kimmel said. Kimmel also made the remarks before authorities made texts that suggested the suspected killer was politically opposed to Kirk.

Kimmel’s comment quickly generated controversy until the FCC, which oversees all broadcasts in the US, demanded that action be taken against the host.

Kimmel is not the only person who has received sanctions for remarks made in the Kirk murder.

According to Zhou-Castro, “there have been well-known journalists, analysts, and just regular people who have lost their jobs as a result of comments” they made about Charlie Kirk’s passing.

She claimed that US Vice President JD Vance advocated for people to report to their employers if anyone said something disparaging about Kirk on social media, etcetera.

FCC Chairman Carr told The Hollywood Reporter he wanted to thank the company for “doing the right thing” after learning Kimmel had been canceled from Nexstar.

An unnamed source told The Hollywood Reporter that at least one other station group had contacted ABC about the Kimmel show, suggesting that an affiliate revolt might have been a factor.

Kimmel’s appointing is the latest in a string of firings over the past week brought on by a conservative backlash against public criticism of Kirk’s death.

Conservatives mourned Kirk as a martyr who fought for open debate, Christian values, and patriotism. Some people have criticized his divisive views, including those against immigration and Islamophobia, while others have also hailed his passing.

Several journalists, academics, and doctors have been fired or under investigation by their employers because of comments made about Kirk, which is in line with the widely denounced left-wing cancellation campaigns of recent years and stoking controversy over the restrictions of free speech in the US.