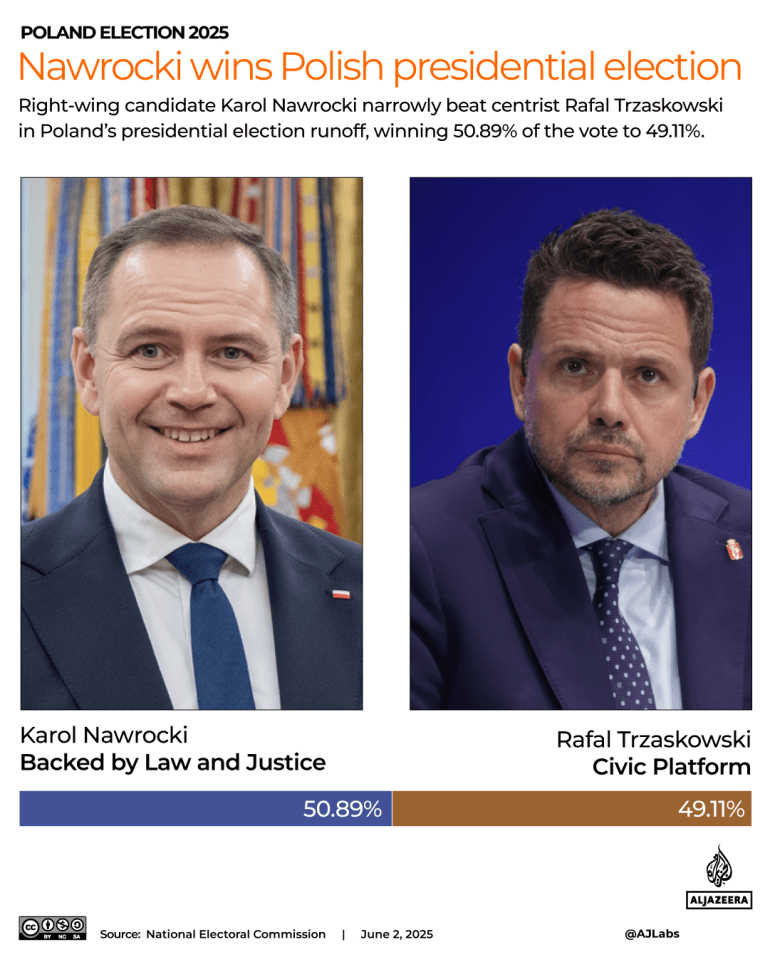

Karol Nawrocki, Poland’s right-wing opposition candidate, narrowly won the second round of voting in the country’s presidential election on Sunday, according to the National Electoral Commission (NEC).

Here is all you need to know about the results:

Who won the presidential election in Poland?

Nawrocki won with 50.89 percent of the votes, the NEC website updated early on Monday.

He defeated liberal Warsaw Mayor Rafal Trzaskowski, who secured 49.11 percent of the vote.

The outcome was a surprise because exit polls had projected a narrow loss for Nawrocki.

What happened in the first round of the election?

The first round took place on May 18, where, as expected, none of the 13 presidential candidates could manage to reach a 50 percent threshold.

Trzaskowski won 31.4 percent of the vote, while Nawrocki got 29.5 percent. As the top two candidates, Nawrocki and Trzaskowski proceeded to the run-off.

Who is Karol Nawrocki, Poland’s new president?

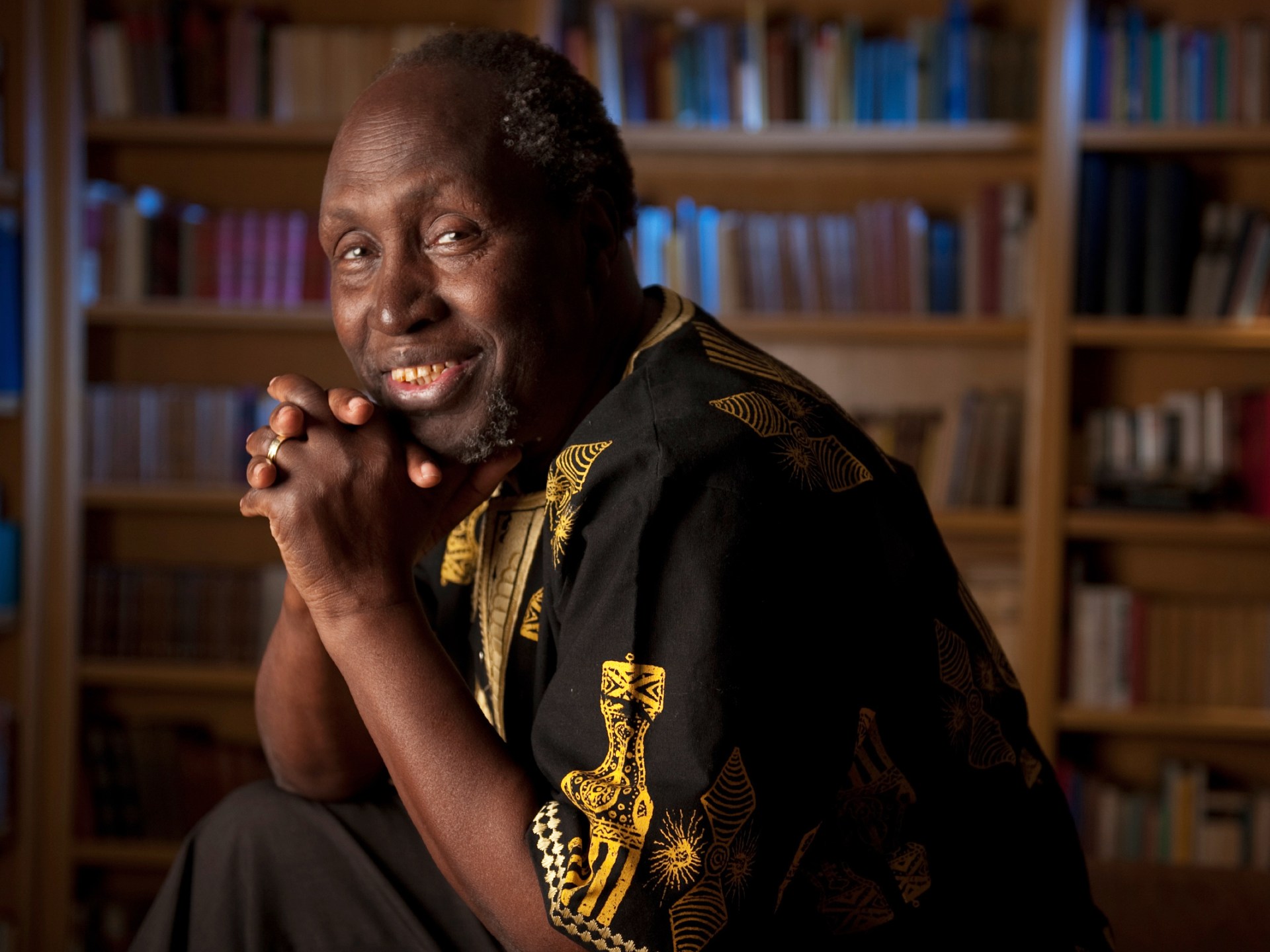

Nawrocki, 42, is a conservative historian and amateur boxer.

He contested as an independent candidate, backed by the outgoing president, Andrzej Duda’s Law and Justice (PiS), Poland’s main opposition party.

The newly elected president’s academic work, as a historian, centred on anti-communist resistance. At the moment, he runs the Institute of National Remembrance, a Warsaw-based government-funded research institute that studies the history of Poland during World War II and the period of communism until 1990.

At the institute, Nawrocki has removed Soviet memorials, upsetting Russia.

He administered the Museum of the Second World War in the Polish city of Gdansk from 2017 to 2021.

Nawrocki has had his share of controversies. In 2018, he published a book about a notorious gangster under the pseudonym “Tadeusz Batyr”. In public comments, Nawrocki and Batyr praised each other, without revealing they were the same person.

United States President Donald Trump’s administration threw its weight behind Nawrocki in the Polish election. The US group Conservative Political Action Conference (CPAC) held its first meeting in Poland on May 27. “We need you to elect the right leader,” US Homeland Security Secretary Kristi Noem said during the CPAC event.

Calling Trzaskowski “an absolute train wreck of a leader”, Noem said, “I just had the opportunity to meet with Karol and listen: he needs to be the next president of Poland. Do you understand me?”

How did Nawrocki win?

Experts say the consistency of Nawrocki’s messaging on the campaign trail may have earned him his win.

“People choose someone they see as strong, clear, and consistent,” Liliana Smiech, chairwoman of the Foundation Council at Warsaw Institute, a Polish nonprofit think tank specialising in geopolitics and international affairs, told Al Jazeera.

“Even with the accusations against him, voters preferred his firmness over Trzaskowski’s constant rebranding. Trzaskowski tried to be everything to everyone and ended up convincing no one. Nawrocki looks like someone who can handle pressure. He became the president for difficult times.”

Unlike Trzaskowski, Smiech said, Nawrocki “didn’t try to please everyone”.

Yet he managed to please enough voters to win.

What is the significance of Nawrocki’s win?

Most of the power in Poland rests in the hands of the prime minister. The incumbent, Donald Tusk, leads a centre-right coalition government, and Trzaskowski was the ruling alliance’s candidate.

Nawrocki has been deeply critical of the Tusk administration. The president has the ability to veto legislation and influence military and foreign policy decisions.

On the campaign trail, Nawrocki promised to lower taxes and pull Poland out of the European Union’s Pact on Migration and Asylum, an agreement on new rules for managing migration and setting a common asylum system; and the European Green Deal, which sets benchmarks for environmental protection for the EU, such as the complete cessation of net emissions of greenhouse gases by 2050.

Like other candidates, including Trzaskowski, Nawrocki called for Poland to spend up to 5 percent of its gross domestic product (GDP) on defence. Poland spent 3.8 percent of its GDP on military expenditure in 2023, according to World Bank data.

“Some expected a wave of support for the left or liberal side, especially among young people. That didn’t happen. Nawrocki won in the 18-39 age group,” Smiech said.

“It’s a clear message: people still care about sovereignty, tradition, and strong leadership. Even younger voters are not buying into the idea of a ‘new progressive Poland’.”

What were the key issues in the Polish election?

The Russia-Ukraine war, which began in February 2022, is a concerning issue for the Poles, who are fearful of a spillover of Russian aggression to Poland due to its proximity to Ukraine.

While Poland initially threw its full support behind Ukraine, tensions have grown between Poland and Ukraine.

Nawrocki is opposed to Ukraine joining NATO and the EU.

Yet, at the same time, Poland and Nawrocki remain deeply suspicious of Russia.

On May 12, the Polish Ministry of Foreign Affairs said an investigation had revealed that Russian intelligence agencies had orchestrated a massive fire at a shopping centre in Warsaw in May 2024. This is why multiple candidates in this election proposed raising the defence budget to 5 percent of the GDP.

Abortion is a key issue in Poland, which has some of the strictest abortion laws in Europe. In August 2024, Prime Minister Tusk acknowledged that he did not have enough backing from parliament to deliver on one of his key campaign promises and change the abortion law. PiS, which backed Nawrocki, is opposed to any legalisation of abortion.

Other issues included economic concerns about taxes, housing costs and the state of public transport.

What’s next?

Nawrocki is expected to be sworn in on August 6.

Smeich said Nawrocki will need to prove that he is not just good at campaigning, but also at governing.