With older brothers Henrik and Filip on either shoulder, escorting him up through the field like bouncers, Jakob Ingebrigtsen hit the front of the European 1500m final.

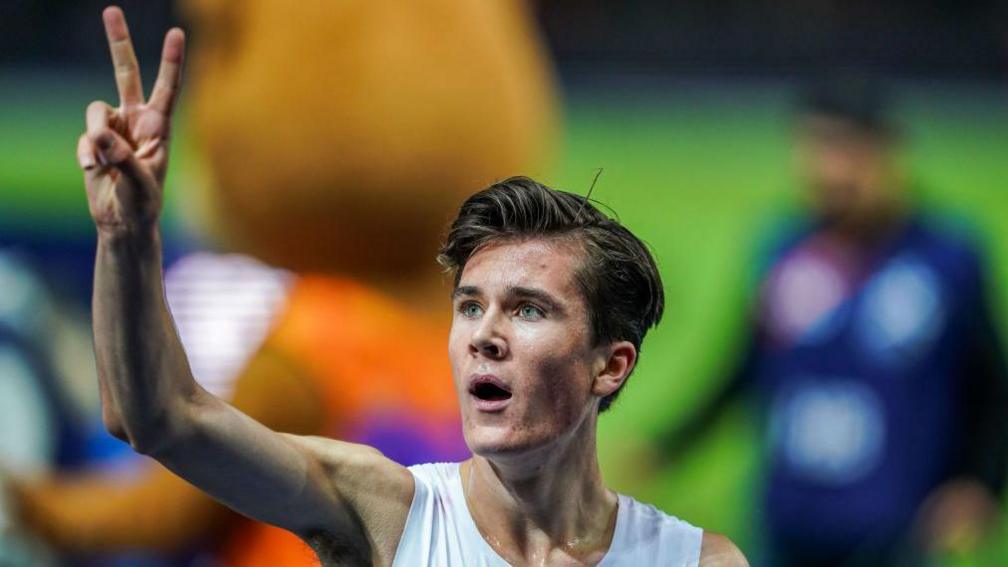

From there, though, the 17-year-old went where no-one could follow.

His long, loping stride ratcheted up in rhythm over the final two laps, squeezing lungs and fraying rivals’ form behind him.

After covering the opening 800m in more than two minutes, Jakob stormed through the next 400m in 56.5 seconds.

He came into the home straight with a chasm of clear air between him and the rest.

As he crossed the line in Berlin’s Olympic Stadium he became the youngest European track champion in history.

The following day he won 5,000m gold as well.

“I’ve been a professional runner since I was eight, nine, 10 years old,” said Jakob back then in August 2018.

“I’ve been training, dedicated and following a good structure – the same as my brothers – from an early age. Winning a second title in two days is the result of having done this my whole life.”

The previous year he had become the youngest person to run a sub-four-minute mile.

Gjert had no background in athletics, but the former logistics manager poured himself into constructing a gruelling high-mileage programme to turn his seven children into a family band of elite middle-distance contenders.

Gjert’s public advice to Jakob after that 1500m gold in Berlin was to celebrate with a glass of warm milk and head straight to bed.

However, according to Jakob, the guidance wasn’t always so wholesome.

In March this year, the Olympic champion stood in a courtroom in his native Norway and claimed he had been subjected to a decade of physical and mental abuse by his father.

The stories were grim.

Jakob said Gjert had threatened to drag him out of a car and beat him to death during one argument.

Jakob said he would routinely be punched around the head, on some occasions until he vomited. He said he was hit when he was late for a race. And again when he got a bad school report.

In another incident, he claimed he was kicked in the stomach after he fell off a push scooter as a nine-year-old.

Gjert denied it all.

He admitted he was a strict parent. “Traditional” and “patriarchal” were his own descriptions of his style.

Gjert was only four when he lost his own father, and he said he lacked any role models when he became a father in his early 20s.

He said he was sometimes angry, often over-protective, but never abusive.

The dispute was shocking. But perhaps not surprising.

In 2019 Gjert and Jakob spoke to BBC Sport about their relationship.

“The boys come to me and say ‘I want to be a European champion’,” Gjert explained.

“I say ‘I want to help you – I can help you – but you have to do everything that I tell you.’

A 19-year-old Jakob, having moved out of the family home to escape Gjert’s all-consuming influence, was already voicing reservations about the arrangement.

“There are lots of ups and downs about having a father as a coach,” he said.

“For other athletes I wouldn’t recommend it because it is too much hard work and you also want a father outside of running.

“For now, and basically our whole lives, he has been a coach because we have asked ourselves what is the most important – do we want to have a family or do we want to run fast?”

Ultimately the court could not discern a truth between their two different accounts.

What is beyond doubt is the decimation of a family who have been a source of fascination and speculation in their native Norway and far beyond.

Gjert, who has accused his sons of a “perfect character assassination”, was always of a simple belief.

For him, the best for his children was being the best.

By that measure, Jakob’s multiple gold medals at world and Olympic level show success.

In an Instagram post on the day of the verdict, Jakob chose another metric.

He listed his track achievements but added that “the one goal I care most about is that Filippa [his one-year-old daughter] will love and respect me for her upbringing”.

Jakob, who won a rare 1,500m-5,000m double at the World Indoor Championships in March, will return to the track once an Achilles tendon injury settles down.

His imperious frontrunning style, unwavering belief and outspoken rivalry with Britain’s Josh Kerr will make him one of the sport’s biggest draws.

The future for Gjert is less clear.

Since his split from his sons, he started coaching one of his their domestic rivals, Narve Gilje Nordas.

Gjert guided Nordas to world 1500m bronze in 2023, even while the dispute with Jakob meant the Norwegian federation kept him from attending some events and training camps.

Related topics

- Athletics