Srinagar, India-administered Kashmir – Hafsa Kanjwal’s book on Kashmir has just been banned, but it’s the irony of the moment that strikes her the most.

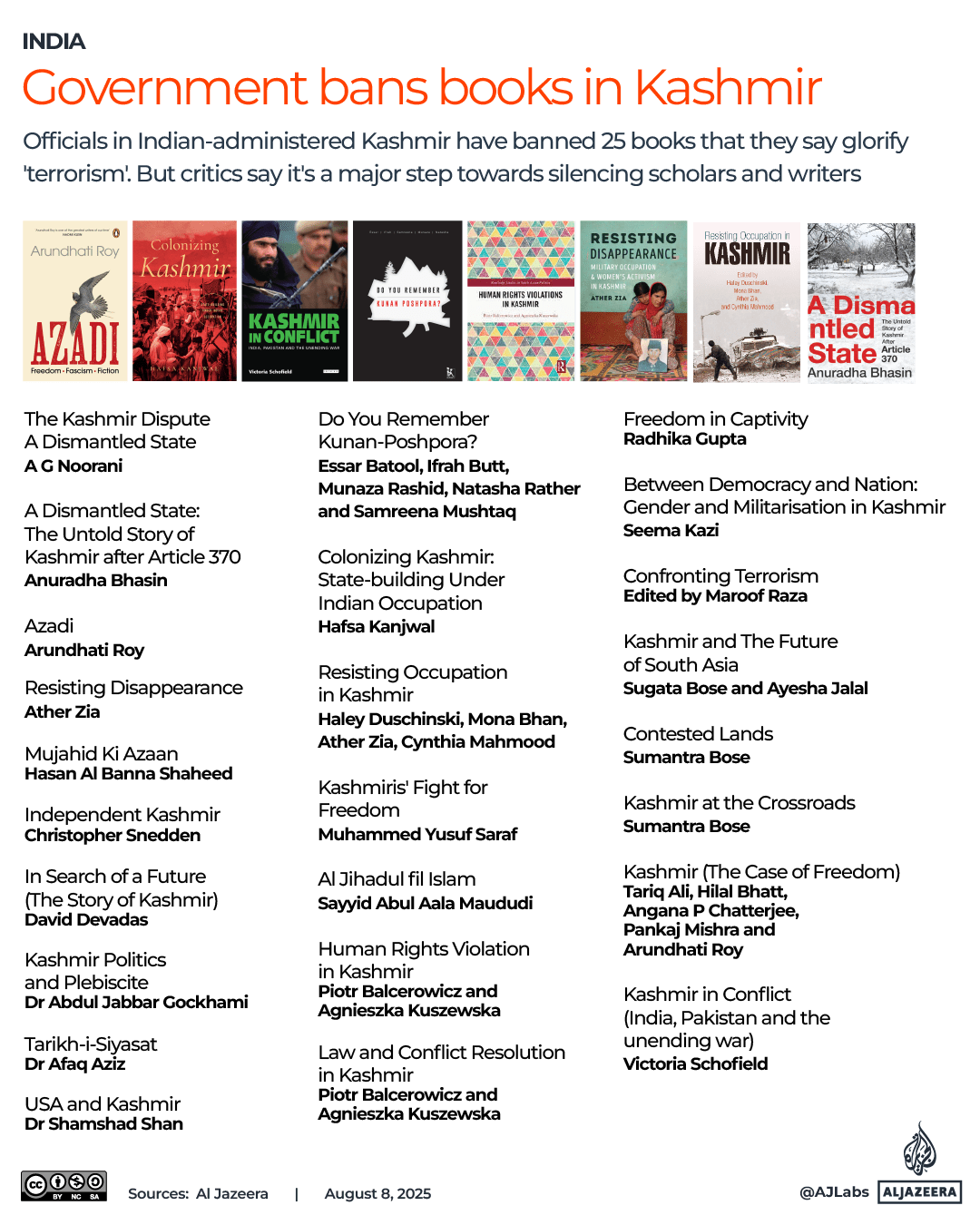

This week, authorities in India-administered Kashmir proscribed 25 books authored by acclaimed scholars, writers and journalists.

The banned books include Kanjwal’s Colonizing Kashmir: State‑Building under Indian Occupation. But even as the ban was followed by police raids on several bookstores in the region’s biggest city, Srinagar, during which they seized books on the blacklist, Indian officials are holding a book festival in the city on the banks of Dal Lake.

“Nothing is surprising about this ban, which comes at a moment when the level of censorship and surveillance in Kashmir since 2019 has reached absurd heights,” Kanjwal told Al Jazeera, referring to India’s crackdown on the region since it revoked Kashmir’s semiautonomous status six years ago.

“It is, of course, even more absurd that this ban comes at a time when the Indian army is simultaneously promoting book reading and literature through a state-sponsored Chinar Book Festival.”

Yet even with Kashmir’s long history of facing censorship, the book bans represent to many critics a particularly sweeping attempt by New Delhi to assert control over academia in the disputed region.

‘Misguiding youth’

The 25 books banned by the government offer a detailed overview of the events surrounding the Partition of India and the reasons why Kashmir became such an intransigent territorial dispute to begin with.

They include writings like Azadi by Booker Prize winner Arundhati Roy, Human Rights Violations in Kashmir by Piotr Balcerowicz and Agnieszka Kuszewska, Kashmiris’ Fight for Freedom by Mohd Yusaf Saraf, Kashmir Politics and Plebiscite by Abdul Gockhami Jabbar and Do You Remember Kunan Poshpora? by Essar Batool. These are books that directly speak to rights abuses and massacres in Kashmir and promises broken by the Indian state.

Then there are books like Kanjwal’s, journalist Anuradha Bhasin’s A Dismantled State: The Untold Story of Kashmir After Article 370 and legal scholar AG Noorani’s The Kashmir Dispute 1947-2012, which dissect the region’s political journey over the decades.

The government has blamed these books for allegedly “misguiding youth” in Kashmir and instigating their “participation in violence and terrorism”. The government’s order states: “This literature would deeply impact the psyche of youth by promoting a culture of grievance, victimhood, and terrorist heroism.”

The dispute in Kashmir dates back to 1947 when the departing British cleaved the Indian subcontinent into the two dominions of India and Pakistan. Muslim-majority Kashmir’s Hindu king sought to be independent of both, but after Pakistan-backed fighters entered a part of the region, he agreed to join India on the condition that Kashmir enjoy a special status within the new union with some autonomy guaranteed under the Indian Constitution.

But the Kashmiri people were never asked what they wanted, and India repeatedly rebuffed demands for a United Nations-sponsored plebiscite.

Discontent against Indian rule simmered on and off and exploded into an armed uprising against India in 1989 in response to allegations of election fixing.

Kanjwal’s Colonizing Kashmir sheds light on the complicated ways in which the Indian government under its first prime minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, consolidated its control over Kashmir.

Some of Nehru’s decisions that have come under criticism include the unceremonious dismissal of the region’s leader Sheikh Abdullah, who advocated for self-rule for Kashmir, and the decision to replace him with his lieutenant, Bakshi Ghulam Muhammad, whose 10 years in office were marked by the strengthening of New Delhi’s rule of Indian-administered Kashmir.

Kanjwal’s book won this year’s Bernard Cohn Book Prize, which “recognizes outstanding and innovative scholarship for a first single-authored English-language monograph on South Asia”.

Kanjwal said the ban gives a sense of how “insecure” the government is.

‘Intensification of political clampdown’

India has a long history of censorship and information control in Kashmir. In 2010, after major protests broke out following the killing of 17-year-old student Tufail Mattoo by security forces, the provincial government banned SMS services and restored them only three years later.

At the height of another civil uprising in 2016, the government stopped Kashmir Reader, an independent publication in Srinagar, from going to press, citing its purported “tendency to incite violence”.

Aside from prohibitions on newspapers and modes of communication, Indian authorities have routinely detained journalists under stringent preventive detention laws in Kashmir.

That pattern has picked up since 2019.

“First they came for journalists, and realising they were successful in silencing them, they have turned their attention to academia,” said veteran editor Anuradha Bhasin, whose book on India’s revocation of Kashmir’s special status in 2019 is among those banned.

Bhasin described the accusations that her book promotes violence as strange. “Nowhere does my book glorify terrorism, but it does criticise the state. There’s a distinction between the two that authorities in Kashmir want to blur. That’s a very dangerous trend.”

Bhasin told Al Jazeera that such bans will have far-reaching implications for future works being produced on Kashmir. “Publishers will think twice before printing anything critical on Kashmir,” she said. “When my book went to print, the legal team vetted it thrice.”

‘A feeling of despair’

The book bans have drawn criticism from various quarters in Kashmir with students and researchers calling it an attempt to impose collective amnesia.

Sabir Rashid, a 27-year-old independent scholar from Kashmir, said he was very disappointed. “If we take these books out of Kashmir’s literary canon, we are left with nothing,” he said.

Rashid is working on a book on Kashmir’s modern history concerning the period surrounding the Partition of India.

“If these works are no longer available to me, my research is naturally going to be lopsided.”

On Thursday, videos showed uniformed policemen entering bookstores in Srinagar and asking their proprietors if they possessed any of the books in the banned list.

At least one book vendor in Srinagar told Al Jazeera he had a single copy of Bhasin’s Dismantled State, which he sold just before the raids. “Except that one, I did not have any of these books,” he shrugged.

More acclaimed works on the blacklist

Historian Sumantra Bose is aghast at the suggestion by Indian authorities that his book Kashmir at the Crossroads has fuelled violence in the region. He has worked on the Kashmir dispute since 1993 and said he has focused on devising pathways for finding a lasting peace for the region. Bose is also amused at a family legacy represented by the ban.

In 1935, the colonial authorities in British India banned The Indian Struggle, 1920-1934, a compendium of political analysis authored by Subhas Chandra Bose, his great-uncle and a leader of India’s freedom struggle.

“Ninety years later, I have been accorded the singular honour of following in the legendary freedom fighter’s footsteps,” he said.

As police step up raids on bookshops in Srinagar and seize valuable, more critical works, the literary community in Kashmir has a feeling of despondency.

Source: Aljazeera

Leave a Reply