Ashley Haruna had no intention of staying in Ghana, despite the fact that she had no intention of doing so. But everything changed for the 28-year-old health coach when she stood facing a dark cell inside the stone walls of Cape Coast Castle. Haruna claims she “felt something” as the tour guide explained that many of the exiled people had ended up in Haiti.

Having grown up in the United States to Haitian parents, she realised “my ancestors could’ve passed through here. This location This ground.

She reflects, “I wasn’t looking for that.” “But it found me. ”

The feeling it stirred within her only grew when she returned home to Ohio. She eventually returned to Ghana after a short while, with her family’s uneasy approval.

That was in December 2021, and Haruna was following in the footsteps of many other African Americans who had sought to reconnect with the country that may once have been home to their ancestors.

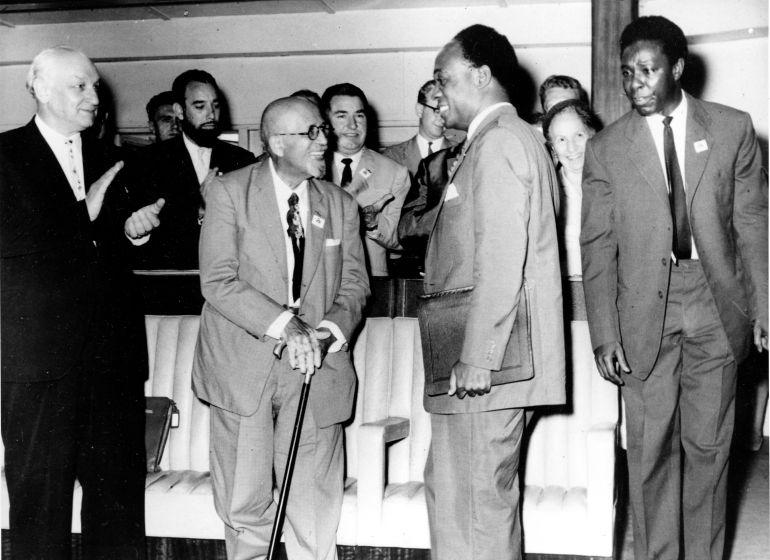

Kwame Nkrumah, Ghana’s first prime minister and president, pushed for the diaspora’s return as part of his efforts to create a nation-by-the-number in the 1950s. During the US civil rights movement, he invited Black American activists, including W E B Du Bois, Marcus Garvey, and Julian Bond, to relocate to Ghana. De Bois and Maya Angelou both moved there in the 1960s.

Ghanaian leaders continue to encourage the African diaspora to reconnect and relocate. More than 200 people from the US and the Caribbean received Ghanaian citizenship in 2019 as part of the “Year of Return” commemorating 400 years since the first Africans were enslaved in Virginia. In 2024, as part of the government’s “Beyond the Return” initiative – the same programme that encouraged Haruna to move to Ghana – 524 African diasporans were granted citizenship.

However, as Haruna discovered, creating a new life in Ghana presents challenges.

Diaspora Diaspora Villa

Her first apartment was located two hours north of Accra, in the mountainous Eastern Region, and while Haruna had imagined herself integrating into a local community, she instead found isolation. She found herself feeling alone and frustrated because there were no nearby grocery stores and no one to assist her with questions about how to use a gas stove or what to do if the water stops running.

She recalled a YouTube video she’d seen while still in the US about a place called Diaspora Diaspora Villa – a co-living space where the owner, herself a “returnee”, as African Americans relocating to Ghana refer to themselves, helps others navigate their new lives in the country. Haruna dug through her browser history until she found the video. A week later, she moved into the villa in an upscale suburb of Accra.

She learned to navigate the practical and cultural difficulties of finding her new home in the warm communal living room and kitchen she shared with two other African-American tenants. These included learning to say “please” before every word.

When Haruna was injured in a car accident, it was the villa’s owner, Michelle Konadu, 37, and the community of former tenants who helped her. Her lifeline was the villa. Like the other tenants – who tend to stay for between three and nine months – Haruna moved out of the villa after a while, but it is still Konadu she calls when she needs help.

‘They want healing’

Konadu is aware of the conflict created by other worlds. Born and raised in New York City to Ghanaian parents, her family apartment was a landing place for visiting relatives, distant cousins and friends of friends. She claims that “we were always residing someone.”

It wasn’t until she visited Ghana for a funeral in 2015 that she first contemplated leaving the fast pace of New York for the slow flow of Ghana. She initially assumed it would feel like home, but she claims she frequently felt alien. “Too American to be in Ghanaian spaces. But America would not be able to tolerate it because of Ghana.

A cousin named Alfred softened her landing by teaching her how to navigate markets, hail a trotro (a local minibus taxi), and understand the unspoken etiquette of greeting elders and never using the left hand to make gestures towards anybody.

She claims that she might have left and never come back without his advice.

Recognising that not every returnee has their own Alfred, Konadu decided to help. In 2017, she opened Diaspora Diaspora Villa, a three-bedroom co-living compound alongside her larger family home in Kwabenya. She invites the tenants she hosts into the everyday life of her neighbourhood and introduces them to middle-income Accra. Beyond providing accommodation, she helps returnees find schools, consults on land purchases, and connects them with social groups and sports clubs.

Her goal is simple: to help people belong by providing “an already-made community”.

The majority of them arrive in this country on a soul mission, Konadu explains. “They want healing. or reconnecting. Or just a fresh start. Many people have a lifelong dream of visiting Africa. But the people they meet might not understand that. ”

When their intended destination was to leave, her family was unable to comprehend why she had relocated. But now other families are relieved to know that their loved ones will spend their first months in Ghana surrounded by people on a similar journey. Konadu believes that if people can live with her, they can also live in the community as a whole after ten years.

She points to the Brazilian “Tabom” community in Jamestown, Accra, which she sees as a perfect example of a well-integrated returned diaspora group. In the 19th century, they emigrated from Brazil as slaves, settled among the Ga people, had intermarried, had language training, and had a way of living that incorporated their Afro-Brazilian heritage into the social structure. Over the generations, their names – De Souza, Silva, Nelson – have become part of the Jamestown story. Konadu anticipates that the younger returnees will experience the same fate, and that the strong African-American culture will remain a part of larger Ghanaian society.

Haruna understands that integration takes time, and she acknowledges that returnees like her have privileges that others in Ghana don’t. Her preferential treatment includes faster service in restaurants, locals ready to help, and her ability to generally make things happen more quickly, like meetings with authorities, because lighter skin and an American accent frequently open doors in ways that never happened back in the US.

“It is uncomfortable as a self-aware person to notice that I have privilege, something that is the total opposite of what is happening in the United States. She says, “I’m still getting my head around it.”

“I’m Ghanaian. I’ve returned, too, says Konadu. “We’ve always been connected: Ghana and its diasporans. Although this isn’t new, the “Year of Return” made things more obvious. ”

Some friction has resulted from this increased visibility and the clustering of returnees in particular settlements, which add to the cost increase.

They won’t see the Ghana, they say.

Anthony Amponsah Faith runs a business renting out cars and driving clients around Ghana, including returnees navigating the country for the first time. He attributes their permission to lead him to places like the middle-belt waterfalls and the Nzulezu stilt village, which he had never visited before. “Before, I never got to go anywhere. The 32-year-old claims to have seen the entirety of Ghana now.

On these trips, Amponsah has witnessed his African-American clients’ emotional visits to coastal slave castles and memorials, but he has also seen friction up close. While wealthy neighborhoods, where returnees frequently settle, have access to supermarkets and cafes, and have access to paved roads and supermarkets, have water on cycles, while basic services need improvisation. Returnees complain about power cuts or heavy traffic, while locals shrug them off as part of daily life. He recalls a client who argued that Ghana should be affordable and that he was being overcharged.

Earlier this year, Amponsah awoke one night to find his mattress floating in a room flooded with water. He claims that Ghana won’t be seen there. “It doesn’t flood in the areas where returnees stay. ”

He is frustrated by the rising cost of housing, which he attributes to returnees’ willingness to pay more. He claims that it is not expensive to them. “They come from places where they earn more. However, I hold the government accountable. Why aren’t we getting those same opportunities? ”

In 2019, he paid 120 cedis ($10-12) a month for a small studio; he now pays 450 cedis ($42-44).

“The cost of living is rising by the second. Finding a place is scary because of it, Amponsah claims. He would prefer to be closer to his customers, many of whom live at least an hour away, but he can’t afford to move.

‘A town from scratch’

Some Ghanaians carry an often unspoken burden due to their ancestors’ involvement in the transatlantic slave trade, which makes some chiefs offer land to returnees as atonement. Many newcomers feel guilty about their economic and social privileges.

Across Ghana, at least two diaspora settlements, Fihankra and Pan African Village emerged that way, while other returnee-focused residential projects, including gated communities, are under construction.

In the African-American community known as Pan African Village, businessman and investor Dawn Dickson is constructing a house for herself. She moved to Ghana in 2022, after envisaging a life outside the US in a place where she wasn’t “the minority”.

The 46-year-old claims she had no intention of looking for a diaspora-only community. Dickson, who traces her ancestry to the Akan people in Ghana and Ivory Coast, was struck by the sense of familiarity, warmth and energy among the Ghanaians she met. However, when she began to look for land, she discovered that other returnees were purchasing property close to Asebu, in the coastal Central Region, where a traditionalist had carved out 20,000 plots for diasporans.

“For me, it was the excitement that I got to be part of building a town from scratch,” Dickson explains.

She purchased land before starting a business to assist other African Americans in purchasing and building homes. Dickson is employing sustainable rammed earth technology to construct houses for 35 returnees as well as roads, a school, a church and boreholes, and is training locals to master this building technique.

However, there have been some unanswered questions in the community.

In 2023, a family challenged the decision to allocate land they claimed was their ancestral property as part of the village. Despite a high court’s ruling requiring the suspension of construction, progress has continued, and 150 farmers who depended on this land claim to have lost their lives.

Dickson says the land she has helped purchase is not contested, and if farmers are using it, she negotiates shared-crop agreements or payment.

In other instances, new diaspora initiatives are being worked on and are being investigated.

Sanbra City (“Return City”) is a 300-acre private real estate development outside Accra. Initial rumors that the government was behind an exclusive returnee enclave with homes starting at $ 80,000, which is beyond the reach of most Ghanaians, caused a backlash against the planned eco-friendly gated community. Sanbra City founders have said the project is a collaboration between African-American and Ghanaian developers, not a government initiative, and Ghanaians would be welcomed.

Dickson claims she has witnessed other instances of African Americans defrauding themselves by charging outrageous prices for services rendered by a scammer.

A hub for the local community and a pan-African refuge

The very first planned diaspora community in the country was Fihankra, on the outskirts of Akwamufie town in Ghana’s southeastern Eastern Region.

The Akwamu Traditional Area chief gave land to diasporans who wanted to resettle in Ghana in 1994. Fihankra is a Twi phrase that loosely translates as, “When you left this place, no goodbyes were bid. It represents the agonizing separation of diasporas from their ancestral homes.

Once promoted as a Pan-African refuge, Fihankra is now largely deserted and marked by scandal.

In the late 1990s, when she and her husband were residing in London, retired nurse and Afro-Caribbean Afro-Caribbean, Harriet Kaufman, 69, first learned about Fihankra.

By the time they arrived in Ghana in 1998, rumours were swirling that Fihankra turned away Jamaicans and Nigerians, reserving land solely for African-American investors and charged inflated prices and rents. So the couple settled down on their own and slowly constructed a 15-minute residence in Fihankra.

Over time, some diasporans at Fihankra started calling themselves the royal family, prompting the minister in charge of chieftaincy to take legal action against them for impersonation. Then, in a 2015 attempted robbery, two female African-American residents were killed. Soon after, the small community was largely abandoned.

Only two people, according to Kaufman, reside in Fihankra today.

The Kaufmans’ home, meanwhile, named Black Star African Lion and situated on hills overlooking the Volta River, has grown into a local community hub with a small children’s library, cafe, bar, music studio, guesthouse and prenatal care business.

‘I am fortunate’

It took years for the community to grow, and Kaufman is moved by how quickly returnees appear today. When she first came to Ghana, she and her husband rented from a family in Accra and it took them several years to find land and build the first building. No electricity or smartphones were available in the area. There was no Instagram to glamourise the journey or real estate agents curating “Africa” from afar. Social media, in her opinion, has made return appear simple and even luxurious.

“I guess it was a different time than now. My husband and I were outside to watch the stars at night as we came, she says. “Today, all these influencers are posting about Ghana on Instagram, and people think it is just easy and nice villas by the river. ”

Kaufman believes this contributes to perceptions that returnees are privileged.

After all these years, when she occasionally sells bananas from her garden on the local market, she is given prices that are lower than what customers would typically accept. She says she is still seen as someone who already has more than enough and shouldn’t be seeking profit. Kaufman claims she understands it and feels privileged to live there.

As more recent arrivals build new lives in local communities or choose to be surrounded by other diasporans, many returnees face integration challenges.

Source: Aljazeera

Leave a Reply