Khan Younis, Gaza Strip – Under international humanitarian law, freedom of movement is a fundamental right, inseparable from other core protections such as the right to life, food and education.

In Gaza, however, freedom of movement has become a tool of control and collective punishment, administered through a complex system of road closures, permits and guarded land crossings.

Recommended Stories

list of 4 itemsend of list

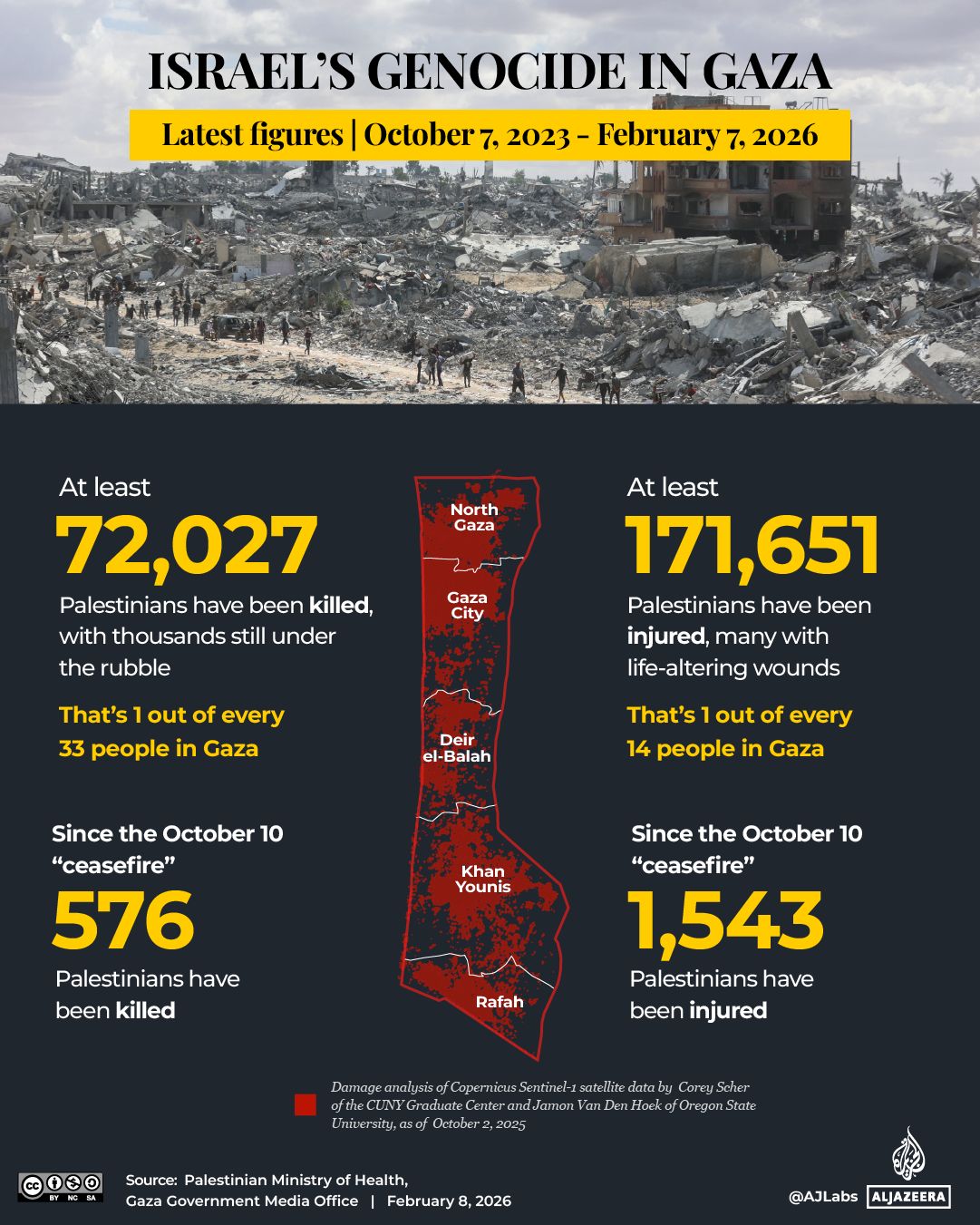

During Israel’s genocidal war on Gaza, which began in October 2023, this system became fully entrenched through the control of gateways: who is allowed in and out, when, in what numbers, and what goods may enter or are barred.

As months passed, closure ceased to be a temporary “security measure” and instead became a daily reality that has redefined survival itself for Palestinians.

A patient in need of medical treatment abroad, a student awaiting an opportunity to study, a family separated across borders, or a wounded war victim on an evacuation list – all ultimately confront the same barrier: Israeli-controlled land crossings.

At the centre of this system stands the Rafah border crossing with Egypt, long viewed as Gaza’s only outlet to the outside world not directly governed by Israel.

In practice, however, Rafah became part of the same control regime. On May 7, 2024, Israel announced it had taken “operational control” of the Palestinian side of the crossing, effectively shutting down a vital lifeline for humanitarian aid and medical evacuations.

In the weeks that followed, media outlets documented how aid trucks were left stranded, and food supplies destined for Gaza had spoiled under the sun, while Rafah remained closed or effectively disabled at the height of humanitarian need.

With its closure, Rafah was transformed from a crossing point into an instrument of collective regulation.

Through numerical caps, name lists and layered approvals, Israeli authorities have exercised full control over movement, with immediate consequences for food supply chains, humanitarian assistance, medical evacuations, and Palestinian civilians’ right to travel and reunite with their families.

Following the closure of the Rafah crossing, the Israeli army selectively opened alternative points for the passage of “pre-approved goods” and limited numbers of patients and humanitarian staff.

The United Nations repeatedly warned about unsafe access to several crossings because of Israeli military activity in Gaza.

The crossings deemed “operational”, which shifted over time, were primarily Karem Abu Salem (Kerem Shalom) and Kissufim.

In reality, this arrangement did not result in a stable flow of aid, but in a volatile system reliant on constantly changing entry points in line with military developments.

In northern Gaza, following Israel’s enforced separation of Palestinians from the south, the UN documented the Israeli army’s closure of multiple key roads and corridors.

This meant restrictions applied not only to “entry into Gaza” but also to “access within Gaza”, further isolating entire areas from supplies and essential services.

Beyond crossings and roads, Israel’s war imposed an additional layer of control through what became known as “mandatory coordination” for humanitarian convoys. Even when aid was permitted to enter, its movement inside Gaza remained contingent on Israeli military approvals, particularly near areas of Israeli troop deployment or on routes leading to crossings.

Data from the UN’s Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) show hundreds of humanitarian missions faced “impediment, cancellation, or denial”.

According to Maha al-Hussaini, advocacy director at the Euro-Med Human Rights Monitor, what unfolded during the genocide was not merely temporary restrictions on freedom of travel, but “a systematic policy through which Israel used control over movement to and from Gaza as a central tool of siege, collective punishment, and coercive management of the civilian population”.

Al-Hussaini told Al Jazeera that under international law, Israel – as the occupying power – is obligated to allow freedom of movement to guarantee “access to food, humanitarian aid, healthcare, education, and family reunification”.

Yet, she said, Israeli practices during the war reflected “a systematic violation of these obligations” through the near-total closure of crossings, strict control over who is permitted to leave or return, and the use of “arbitrary and degrading measures against civilians”.

Medical evacuations: A matter of life or death

The use of movement as a control mechanism is most starkly revealed in the medical evacuation file.

Following Israel’s closure of Rafah, evacuation of the sick and wounded was routed through an extremely complex process, beginning with patient lists and referrals, followed by transfers to gathering points inside Gaza, and then transport to the Karem Abu Salem crossing, where additional Israeli security clearances were required.

This failed miserably in responding to the terrifying scale of the ongoing medical catastrophe in the Strip. It is instead a purposefully slow and heavily conditioned pathway.

Official figures expose a stark gap between demand and reality.

Between May 8, 2024, and January 18, 2025, only 459 patients were evacuated through Karem Abu Salem. During a subsequent ceasefire period between January 19 and March 17, 2025, when Rafah was partially reopened, the number rose to 1,702 patients, including hundreds of children, clearly indicating that evacuations improve only when additional movement routes were available.

Once that period ended and reliance on Karem Abu Salem resumed, evacuations again dropped sharply to just 352 patients between March 18 and July 16, 2025.

By contrast, the World Health Organization (WHO) today reports that more than 18,500 patients in Gaza remain in urgent, life-saving need of medical treatment outside the Strip.

The disparity between need and outcome shows that evacuations conducted over many months addressed only a tiny fraction of actual demand, leaving thousands trapped on open-ended waiting lists in war-battered Gaza.

‘Cruel and inhuman treatment’

More than 1,600 Palestinians have died while waiting for healthcare abroad. In this context, al-Hussaini said restrictions on movement amount to one of Israel’s gravest violations during the genocide.

“Thousands of wounded and ill Palestinians, including children and cancer patients, were denied the ability to travel outside Gaza for medical treatment, or were forced to wait for weeks or months under complex and opaque procedures. In many cases, their health deteriorated or they died before permission to leave was granted,” she said.

“Such practices cannot be justified on security grounds and constitute a direct violation of the right to life, amounting to cruel and inhuman treatment.”

When Rafah was partially reopened this month after the United States applied pressure on Israel’s leaders, the underlying reality did not fundamentally change. On February 2, the WHO announced the evacuation of just five patients and seven companions.

It was a tightly controlled border opening with Egypt governed by multiple layers of scrutiny: small numbers allowed to cross, prior Israeli security authorisation for returnees, European screening at Rafah, followed by a second identification and interrogation process in a corridor administered by the Israeli army.

Al-Hussaini said the restrictions imposed during the war, taken in totality, show that Israel uses freedom of movement in Gaza to regulate the daily life of Palestinians, determining who receives aid, who accesses health treatment, and who remains trapped in the Strip, placing these policies at the heart of legal debates around proportionality, the prohibition of collective punishment, and the obligations of an occupying power.

Blockade as permanent policy since 2007

Israeli restrictions on freedom of movement in Gaza did not begin with the current war. Since 2007, they have evolved from purportedly temporary security measures into a permanent policy structuring the lives of 2.4 million people.

Following Hamas’s rise to power in 2007 through democratic elections, Israel imposed a comprehensive land, sea and air blockade. The International Committee of the Red Cross has consistently stated that the comprehensive closure of Gaza targets the civilian population as a whole, infringes on fundamental rights, and constitutes a form of collective punishment prohibited under international humanitarian law.

UN agencies have similarly stressed that long-term restrictions, even during periods of relative calm, lack any legitimate legal justification.

Economically and socially, the World Bank and the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) have documented how the blockade has paralysed Gaza’s economy, eroded its productive base and driven unprecedented levels of poverty and unemployment. Severe restrictions on goods, raw materials and exports have made any form of sustainable economic recovery impossible, entrenching chronic dependence on humanitarian aid.

Israel further reinforced the blockade by a policy of separating Gaza from the occupied West Bank, treating the Strip as a distinct territorial unit despite their status as a single territory under international law.

UN special rapporteurs and rights groups say this separation has fractured social and family ties, and obstructed access to education, work and healthcare.

For more than 15 years, these restrictions have been recalibrated after each escalation. The severe constraints imposed during the current war are merely an intensification of a system in place since 2007.

Controlling food, water, medicine

In March 2024, OCHA reported that only 26 percent of aid missions were facilitated by Israel’s army, while 40 percent were denied, 20 percent delayed, 11 percent impeded and 3 percent withdrawn.

May 2024 marked a turning point, as crossing closures and restrictions led to a sharp reduction in aid and humanitarian personnel entry.

As security conditions on convoy routes deteriorated, aid increasingly failed to reach the intended destinations. This prompted the UN agency for Palestinian refugees, UNRWA, to suspend aid entry through the Karem Abu Salem crossing on December 1, 2024, citing unsafe conditions and repeated looting incidents. In many cases, aid was unloaded on roads or seized before reaching warehouses.

In August 2025, the Integrated Food Security Phase Classification (IPC), a global hunger monitor, confirmed that famine had taken hold in northern Gaza.

Subsequent updates reiterated that famine risk would persist as long as Israeli military operations continued and humanitarian access remained restricted, noting that the vast majority of the population faced extreme levels of food deprivation.

“Restrictions on movement were among the gravest violations. Movement control was not incidental or administrative – it was used as a central tool to manage and pressure the civilian population,” said al-Hussaini.

She described Israel’s actions as “a clear violation of international humanitarian law, including the prohibition on the use of starvation of civilians as a method of warfare”.

Israeli restrictions fragmented humanitarian flows, increased risks along convoy routes, and at times forced aid agencies to suspend operations entirely.

“The population was left trapped in a cycle of hunger, driven not only by shortages but by the denial of access, freedom of movement, and ultimately the right to survive,” al-Hussaini said.

‘Stripping Gaza of means of life’

After the partial reopening of Rafah last week, only small numbers of patients needing healthcare abroad and separated families were allowed to cross.

As of Sunday, a total of 165 people have managed to leave Gaza into Egypt, and 94 Palestinians were allowed to return. Tens of thousands continue to wait to cross Rafah, including sick and wounded whose lives depend on it.

Al-Hussaini said the impact of movement restrictions extends beyond physical survival, cutting across economic, social and cultural rights.

“Thousands of students were prevented from continuing their education abroad, families were torn apart through the denial of family reunification, and opportunities for work, study and medical treatment were halted,” she said.

Israel’s policies “deepened the psychological and social consequences of the war beyond the scope of direct military operations”.

Continued Israeli control over freedom of movement poses a fundamental obstacle to any genuine reconstruction and social rehabilitation.

“By restricting the entry of materials and equipment, preventing experts and specialised personnel from moving freely, and keeping the population in a state of forced instability, these policies cannot be separated from a broader context aimed at stripping Gaza of the means of life, and imposing a long-term reality of forcible displacement and population control,” al-Hussaini said.

Leave a Reply