The ‘ghost reporters’ writing pro-Russian propaganda in West Africa

A coffin was carried on their shoulders by eight pallbearers, some of whom wore tracksuits with the FIFA logo on them. Alongside them, referee whistles echoed the tune of a song being sung by the funeral procession.

In a sports stadium in the Central African Republic (CAR) in September 2020, hundreds of people gathered to say goodbye to Jean Claude Sendeoli.

Sendeoli was a teacher at a secondary school in the capital, Bangui, and a referee for the country’s football federation. After his death, students posted messages on the school’s Facebook page to remember their much-loved teacher while FIFA named him in its 2020 obituaries, closing the book on his journey.

But no one was aware that his identity was still unknown even after he was cremated.

In the years that followed, photos of Sendeoli would become part of a pro-Russian propaganda campaign – one that used his image to create a fake persona whose articles have been published in media outlets in more than a dozen African countries.

And it was the images and videos of his final farewell that enabled Al Jazeera to uncover the propaganda campaign and establish that a man who lied to be a geopolitical expert lacked any existence.

Paid-for content

“Good evening, sir. The Investigative Unit (I-Unit) of Al Jazeera obtained a February 2022 WhatsApp message containing Aubin Koutele, a journalist for TogoMedia24.

“I would like to know the conditions of publishing an already edited article on your website”, wrote Koutele, who edits and publishes the Togolese news website.

The Burkinabe newspaper quickly responded.

“We will have a look, and if it aligns with our editorial guidelines, we will publish it”, the editor replied.

Like many media outlets around the world, revenue for publications in Burkina Faso has dwindled.

Many people have since turned to finding new sources of income, including producing paid-for content. Usually, these paid articles advertise a product or service, but sometimes they are of a different nature.

This particular instance was one.

Koutele, the journalist who approached the Burkinabe editor, sent over the first of several articles. “Article not signed”, the editor told Koutele, referring to the missing byline.

“I’m sorry,” Gregoire Cyrille Dongobada]is the writer]”, Koutele replied.

The article was published shortly after. Koutele later sent the newspaper payment for the piece, about $80.

Stolen identity

Gregoire Cyrille Dongobada, who currently resides in Paris, is a political and military analyst from CAR, according to his social media profiles. He’s published at least 75 articles, mainly about the political situation in Francophone Africa.

His articles have headlines like “The causes of anti-French sentiment in West Africa” and “France’s jealousy of the successes of the Russian presence in Mali.” He concentrates on the roles of Russia, France, and the UN.

Analysing the articles, a clear viewpoint comes across in almost all of them – one that presents French influence in Africa as detrimental for the continent and the presence of Russian soldiers as beneficial.

But, on closer inspection, some things do not add up about Dongobada.

Dongobada’s first article appeared in February of this year, according to an analysis from the I-Unit, with no evidence that he had ever existed.

He claims to be a political and military expert, yet has no links to any university, think tank or private institution, and there are no research papers or academic publications under his name.

Dongobada appears to only be around social media, with a focus on Facebook and X, as well as writing for publications in French-speaking Africa, including Senegal, Mali, and Burkinabe. Al Jazeera reached out to several of the outlets that published him. None the I-Unit spoke to had ever talked to Dongobada directly.

Additionally, he uses profile pictures on social media.

Dongobada doesn’t just look like Jean-Claude Sendeoli, the teacher and referee whose funeral was held in September 2020. One of Sendeoli’s 2017 photos is flipped right to the left, which indicates that it was merely taken from the deceased man’s Facebook page.

“Someone, whether a state or a nonstate actor, is using the identity of someone who’s died to do their own propaganda”, said Michael Amoah, a political scientist at the London School of Economics, whose research looks at postcolonial politics and power transitions in Africa.

Disinformation researcher Nina Jankowicz said she was “quite surprised they chose someone who has died instead of just using the profile of a living person or potentially using artificial intelligence” to construct the false identity.

More than 15 authors and at least 200 articles published since the beginning of 2021 have been identified as Dongobada, according to an analysis that the I-Unit conducted.

Some of the writers, but not all, had bylines in the paid-for articles Koutele submitted to outlets for publication. In their newspaper bios, the majority of the authors refer to themselves as freelance journalists, with some, like Dongobada, identifying themselves as analysts or experts. However, for each of them, there is no employment history and, in many cases, no social media profile or other evidence to indicate they are a real person.

As with Dongobada, writers who do not appear to exist having written articles critical of France and the UN point to a concerted effort to convey a political message, experts said.

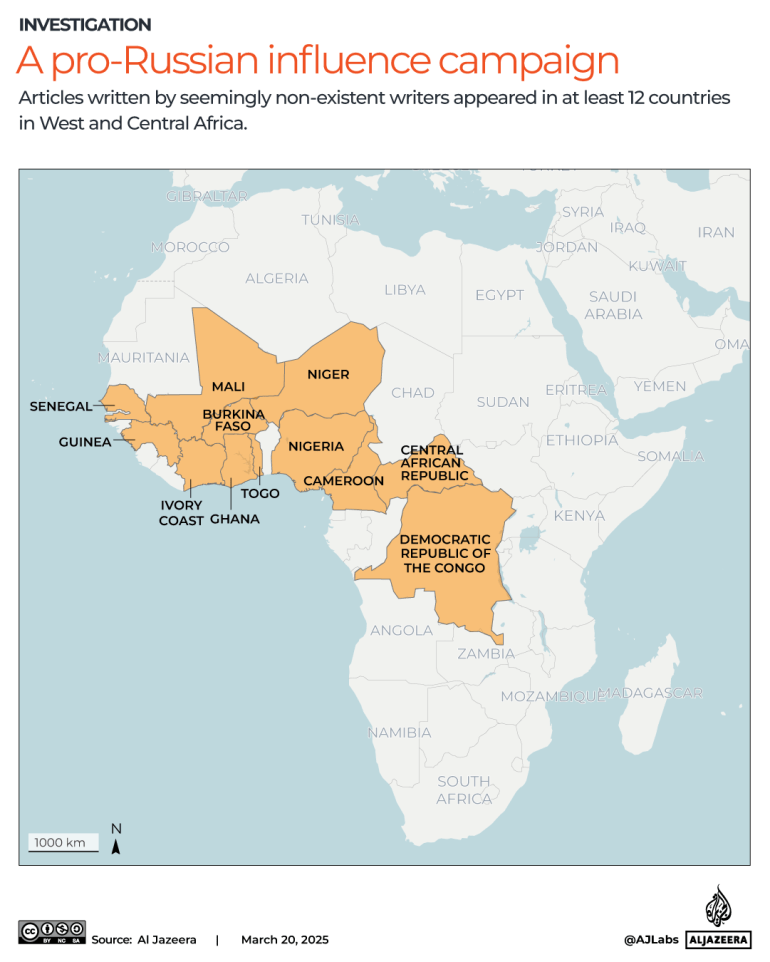

The majority of the articles Al Jazeera examined were remarkably positive about Russia and critical of France’s role in its former colonies. Each of the countries where the articles appeared has seen an increased Russian presence, and some are led by military governments favourable towards Moscow.

According to the experts Al Jazeera spoke with, the article biases and metadata from Koutele’s correspondence were likely obtained from Russia.

“I think a lot of states are engaged in information operations through their covert mechanisms”, Jankowicz said when presented with the I-Unit’s evidence.

“What makes Russia different is that they’re doing this by taking on personas”, added the expert, who is CEO of the American Sunlight Project, which combats online disinformation.

Francafrique falling, Russia rising?

More than a dozen African nations were once under French colonial rule. Now, after decades of economic, military and cultural prominence, its power on the continent is waning – while a growing number of West and Central African leaders open their doors to Russia.

“France wants to maintain Francafrique, which is the political system whereby colonial France keeps its former colonies in check, particularly economically”, Amoah said. These nations have gained independence, but they still lack economic independence.

According to Russian political analyst Alexander Nadzharov, only a small fraction of Africans benefitted under this system.

Nadzharov, who studies Russia’s and France’s role in Francophone Africa, said that the populations of those nations are sick of the current socioeconomic model because they don’t believe it to be effective.

“The key pillar of the Francafrique system is the elite networks”, he said, speaking about France’s influence in the region, where leaders, including Cameroon’s Paul Biya and Ivory Coast’s Alassane Ouattara, are strong French allies. “Everyone has studied in French universities, everyone has bank accounts in France, everyone has assets in France. The elites are perceived as being too closely tied to the West, according to the perception.

As a result, the relationship between France and the populations of many Francophone African countries has become strained. This growing resentment has recently had an impact on many of the region’s internal politics.

In the past five years, there were more than 12 attempted coups in West and Central Africa, and nine of them were successful. Most took place in former French colonies where rulers friendly to – and in many cases supported by – France were in charge.

From Chad and Niger ordering French troops to Senegal, who have been renamed monuments and rewriting textbooks, new leaders have attempted to reduce French influence.

Meanwhile, a regional vacuum is creating an opportunity for Russia to make inroads and increase its influence, such as its involvement in mining in CAR and security in Mali and Burkina Faso.

It appears to be finessing its reputation through media relations campaigns, such as those promoted by Al Jazeera.

“Russia’s MO for a long time has been to identify fissures or grievances in society and to really tear at those fissures, to tear the fabric of society apart”, Jankowicz said.

“Russia has used false amplifiers, fake accounts before, most notably in the]2016] US election”, she explained.

The goal is to promote the pro-Russian viewpoint in the media. And in this case, it’s a viewpoint that probably many people in Africa agree with in the postcolonial world”.

Koutele, a journalist from Togo, contacted the Burkinabe media outlet again over WhatsApp two months later.

“I have another article for you”, he wrote.

“The client agrees with the same price”.

Koutele made it clear for the first time that he was a middleman, approaching and paying local media at someone else’s request.

Other signs suggested he was also just a small cog in a much larger machine.

He sent editors some of the WhatsApp messages that appeared to be from different recipients. This indicated a third party was almost certainly providing Koutele with the articles and money.

By analysing the WhatsApp messages and the original Word documents containing the articles, Al Jazeera found clues as to who was behind the campaign.

Tiny bits of information about the file itself are contained in every digital file. This data can reveal when a file was created, the language of the machine it was created on and even hints about the author.

The files in this instance revealed two noteworthy details. First, part of the metadata of each document was in Cyrillic, the alphabet used in Eastern Europe, something unusual for articles written by French-speaking journalists in Francophone Africa. Second, one of the documents had a 10-digit number in it. A 7 was the first digit of Russia’s country code.

According to Jankowicz, the creators of this influence campaign made “many bumbling errors” when looking at the evidence presented by Al Jazeera.

Using phone number recognition apps, the I-Unit was able to reverse search the 10-digit number. The app revealed the name of the person the phone number belonged to: Seth Boampong Wiredu. In Ghana, both second names are prevalent.

So how did this Ghanaian name end up linked to a Russian phone number in a document that was part of an apparent propaganda campaign in French West Africa?

Although Wiredu’s number appears in this document does not directly indicate his involvement with this campaign, it has a history of being associated with other campaigns.

Influence campaigns and the Wagner Group

Seth Wiredu relocated from Ghana to Russia in 2008 to study in Novgorod, which is located 570 kilometers (355 miles) northwest of Moscow. He spent several years there and started a business as a translator. His Russian tax returns indicate that he had become a citizen of Russia by June 2019.

In 2020, Wiredu found a job working for a company known for its propaganda campaigns: the Internet Research Agency (IRA) based in St Petersburg.

The IRA gained notoriety for its involvement in the 2016 US presidential election. The IRA carried out “a social media campaign designed to provoke and amplify political and social discord in the United States,” according to special counsel Robert Mueller’s investigation into Russian interference in that election.

The company, which had links to Russian intelligence agencies, was founded by Yevgeny Prigozhin, then-head of a mercenary force and a close confidant of Russian President Vladimir Putin.

However, US-based social media platforms like Facebook and Twitter made improvements to their systems to stop coordinated propaganda from state actors like Russia in the future.

According to Jankowicz, “Social media platforms are looking for ads that were purchased in Rupees or fake accounts that Russia has created, so it has had to launder its disinformation.”

“It has had to pay middlemen and individuals to ensure that that information gets out there”.

Before the US presidential election in 2020, CNN made it clear that the IRA had hired people from Nigeria and Ghana to post politically contentious content on Facebook and Twitter.

According to sources CNN spoke to at the time, it was Wiredu who hired and paid them for their work in the campaign. Wiredu denied being involved with the IRA when confronted by CNN.

He made his first appearance in a Russian action film called Tourist in 2021 that chronicles the activities of Russian military personnel in CAR. The film was funded by the Wagner Group, a private military company with close ties to the Russian government founded by Prigozhin, the man who also started the IRA.

Wagner became the standard security apparatus in a number of African nations, most notably CAR, where its main place of business is located. In CAR, Wagner initially came in to train the local army. This would become a blueprint for other countries like Mali and Burkina Faso, where Russia’s military and civilian presence increased after Wagner deployed its fighters. Wagner, formerly known as Africa Corps, is now slowly integrating into the Russian Ministry of Defense.

Some wondered if things would change when Prigozhin died in a suspicious plane crash in 2023 after challenging Putin over his handling of the war in Ukraine. His passing, according to Amoah, did not affect Russia’s plans for Africa.

“When Prigozhin passed, the first thing that happened was Sergey Lavrov, the Russian foreign minister, made direct contact with the African countries where Wagner plays a key role]and said] that although Prigozhin had passed, Russia’s foreign policy remains the same”.

The influence battle

According to both Nadzharov and Amoah, Russia’s aims in West and Central Africa are different from what France has historically been trying to achieve.

Nadzharov cited Russia’s potential as a supplier of fertiliser, weapons, and machinery as evidence that “Russia is interested in very pragmatic cooperation that leads to money flowing into Russia.”

“Because we’re interested in making money, we can offer more … generous terms to those African nations than the French are suggesting”, the Russian analyst said.

“Russia is not trying to make client states out of these countries. Nadzharov continued, “Russia has no desire to do that, nor does it have the capacity to do so.”

Amoah said: “France wants to maintain its influence. They also see competition in Russia. And France has made it quite clear that they would prefer African countries to deal with them rather than Russia”.

This fight for influence has led to both countries adopting their own strategies to persuade local populations of their aims.

Both companies employ very different strategies, according to Amoah.

“Russia will stage propaganda, and we obviously can see that this]influence campaign] is propaganda.

“It’s actually done with France through the appropriate state media.”

Outlets like France24 or Radio France Internationale, which are funded by the French government”, will propagate its own gospel, that ‘ we’re here to support Africa, to fight terrorism, to help support Africa with trade and economic prosperity, ‘ “he noted.

But in the end”, they all have the same agenda really: influence, influence. “

Right to respond

In response to Al Jazeera’s questions about his involvement, Koutele said neither he nor his outlet TogoMedia24 entered into any agreement as part of an influence campaign at the behest of Russia-linked clients and that he was not aware of the existence of a pro-Russian influence campaign.

Koutele claimed to be helping colleagues get published, and that he also denied engaging in any influence campaigns as an intermediary.

” As journalists, we have colleagues all over Africa with whom we collaborate. If they ask for our help, we help them and vice versa, “he told Al Jazeera.

France has been putting its “historical partnership” with Africa into perspective, particularly in the fields of security and finance, according to the French Ministry for Europe and Foreign Affairs.

” France has been militarily involved in the fight against terrorism in the Sahel, particularly in Mali, at the request of the states concerned and with due respect for their sovereignty. “

France has been changing its defense partnerships in order to break away from military bases, it added.

It also said France is no longer present on the governing bodies of the Central Bank of West African States and is open to monetary reforms, given that 14 countries still use the CFA currency tying them to France’s Treasury.

Finally, it stated that French media outlets publishing internationally under the state-owned France Medias Monde are strictly free and independent.

Source: Aljazeera

Leave a Reply