A short, elderly Black woman set out on a 24-kilometer (15-mile) walk from her Alabama, United States, home on a cold December morning in 1931 on a quest for justice. The long trek to the court in Selma was no small undertaking for a person in her mid-70s. However, Matilda McCrear was determined to pursue a legal claim for compensation for the devastation her and her family endured.

Until her death 85 years ago on January 13, 1940, Matilda was the last surviving passenger on the last-ever slave ship bound from the West African coast to North America in late 1859.

Her story began many decades earlier, thousands of miles away from that sharecropping farmstead. Originally named Abake – “born to be loved by all” – the girl later renamed Matilda by her American “owner” came into the world circa 1857, among the Tarkar people of the West African interior.

Little Abake was kidnapped by the Kingdom of Dahomey, located in what is now Benin, along with her mother (later renamed Grace), her three older sisters, and some other relatives in 1859 by rebel soldiers from the kingdom’s now-existent Dahomey. Torn away from the rest of their family, they were victims of an age-old regional warfare which underpinned an equally ancient but persistent trade in slavery reaching across North and East Africa, the Ottoman Empire and eventually the Americas.

Although the precise details of her capture are unknown, Abake and the other captives were probably entrashed by ropes and wooden yokes and forced to travel hundreds of miles to Ouidah, a city in southern Benin, in groups. Their so-called “death march” was the first leg of a long and merciless sojourn.

Once they arrived in Ouidah, slaves would be kept in “barracoons,” or locked rooms where prisoners waited for their new owners to sell them for goods.

Abake and her family members were sold as part of a consignment of slaves to one Captain William Foster, of Canadian origin. In his journal, he wrote, “I went to see the King of Dahomey.” Having agreeably transacted]our] affairs … we went to the warehouse where they had in confinement four thousand captives in a state of nudity from which they gave me liberty to select one hundred and twenty-five as mine, offering to brand them for me, from which I preemptorily forbid]sic], commenced taking on cargo of negroes, successfully securing on board one hundred and ten”.

Foster’s ship, Clotilda – a two-masted schooner, 26 metres (86 feet) in length – is now infamous as the last ship known to have carried slaves across the Atlantic to North America. The importation of slaves had been prohibited since 1808, so it was an illegal journey at this time. Slavery had remained prevalent throughout the southeast of the US (and in some of South America). The Clotilda set sail from Ouidah late in the year, purportedly carrying lumber – the 11-man crew being promised double their normal wage to keep quiet about the true contents, as per an entry in Foster’s journal.

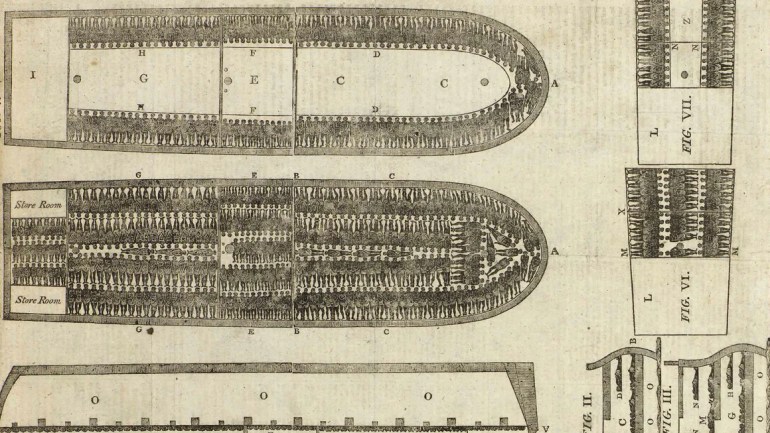

The second section of a triangular trade route connecting Europe, Africa, and the Americas was known as the “Middle Passage,” or as it was known. Ships carried weapons and manufactured goods from Europe to the “slave coast” of West Africa on the first part of the round trip, in the Middle Passage, that cargo was traded for enslaved Africans who were transported to the US and South America, where they were usually sold by auction, and on the final course, the vessels returned to Europe usually laden with cotton, tobacco and sugarcane.

The human cargo had to endure cramped and soiled conditions on the journey to the Middle Passage, which lasted for about 80 days. In the autobiography of an 18th-century slave, Olaudah Equiano, one slaving ship is described as being “so crowded that each had scarcely room to turn himself, almost suffocating us. This produced numerous perspirations, which quickly caused the air to become inebriated with a variety of unpleasant smells, and caused a sickness among the slaves, of which many died.

Separated and sold – a brutal but common fate

At least two million of the roughly 12.5 million enslaved Africans transported to the Americas over the course of 350 years were reportedly killed by the crossing over the Atlantic. Grace would later tell her daughters how she had witnessed her nephew and others from her Tarkar village being simply thrown overboard when they became unwell, apparently to prevent any contagion.

In the early hours of 1860, Foster navigated the Clotilda, which is now carrying 108 slaves, into the port of Mobile, Alabama. He had it towed up the Mobile River to Twelvemile Island, where the captive Africans were transferred to a river steamboat. Foster claimed in his journal that any evidence was then destroyed by the Clotilda.

Foster was eventually charged with illegal slave importation in 1861, but the case was voided because there was no record of the ship’s or manifest’s evidence. It was not until 2019 that researchers found the remains of the Clotilda in the Mobile River, confirming its existence and location.

Foster gave Abake, her mother, and her 10-year-old sister to one of Clotilda’s financial backers, Memorable Creagh, a wealthy plantation owner, at Twelvemile Island.

In another heartbreaking separation, Abake’s two other sisters (whose names are unknown) were sent elsewhere, never to be seen again – a typically brutal fate for so many of those regarded as a mere commodity.

Soon after Abake’s mother and sister arrived on Creagh’s plantation close to Montgomery, Alabama, they found themselves. There, Abake was given the new forename Matilda, her mother was renamed Grace, and her sister as Sally. Grace and a fellow Clotilda survivor, who had been given the name Guy, were forced to wed each other.

Because the couple were classed as “property”, their marriage was not recognised by law, it was simply a means of producing more slave offspring. Slave-owners had complete control over a man’s and woman’s intimate affairs. Grace and Guy were given the surname of their new owner and put to work in his cotton fields.

Matilda’s family was presumably given the least amount of shelter possible; they were crammed together with other families into crude wooden cabins that lacked leaks in wet weather and cold winters and were forced to work seven days a week by their supervisors.

The adult Matilda had only a hazy recollection of those early years, but later recalled one episode when, aged three, she and her sister Sally escaped from the plantation to a nearby swamp where they were scented out by the overseer’s dogs and returned to their quarters.

When the American Civil War started in April 1861, Matilda was still a young child. Alabama, along with Virginia, North and South Carolina, Mississippi, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, Texas, Arkansas and Tennessee, seceded from the US and formed the Confederate States of America – on the grounds that the institution of slavery, the lifeblood of southern economies, was threatened by the federal government in Washington.

On January 1, 1863, President Abraham Lincoln declared that all slaveholders in the Confederate states would be free. This had no immediate effect on Matilda and her family, as the Civil War continued to rage. However, Matilda and her family were freed on June 19, 1865, after the Confederates were defeated.

Matilda would have been about seven years old at this time. Her family moved to Athens, Alabama, and made their home there. It is not known how they supported themselves. Later, Matilda mentioned how she quickly learned the language and would provide interpret services for her mother and stepfather, both of whom encountered difficulties.

They were free, but what would that so-called freedom mean?

Slavery is only referred to as such.

However harsh and unjust the circumstances, enslaved people had some small element of security. A slave owner was at least motivated to ensure the productivity of his human chattels, which necessitated the provision of basic food and shelter.

But after 1865, freed slaves did not find themselves in a friendly world. The notion of Black people as their equals elicited indignant response from many white Americans. In a harsh and unwelcoming world, there were few options for uneducated ex-slaves other than to remain on the plantations as “sharecroppers” – a system whereby a tenant farmed a portion of land in exchange for a share of the crop. Sharecropping frequently involved agreements that, in theory, entangled tenants in debt and poverty.

Upon her emancipation, Matilda and her family thus became supposedly free people. However, “Emancipation for the Negro was only a proclamation,” as Martin Luther King Jr. claimed in a sermon from 1968. It was not a fact. The Negro still endures in various chains, including those of economic segregation, social segregation, and political disenfranchisement.

During the post-Civil War period of “Reconstruction”, many new federal laws promoting racial equality were quickly met by local state measures designed to keep Black people “in their place” and ensure that white people remained ascendant. The state-level response to the US Constitution’s 13th, 14th, and 15th amendments demonstrates this.

The 13th Amendment of 1865 officially ended slavery in all US states and territories. The Freedmen’s Bureau was established to assist freed slaves by providing food, housing, medical assistance, education, and legal assistance for former slaves.

To counter this, southern states, including Matilda’s home of Alabama, enacted the so-called “Black Codes”, curtailing the right of African Americans to own property, conduct business, buy and lease land or move freely in public spaces. Many Black people were forced into sharecropping and other newly exploitative labor practices by the Black Codes.

“vagrancy” laws were a key component of the Black Codes. Through a system known as “convict leasing”, many African-American boys and men were arrested for minor offences such as vagrancy, imprisoned, and then leased out to work for private businesses. This resulted in a new system of forced labor that was essentially slavery once more. Convict leasing was legally rooted in the so-called “exception clause” of the 13th Amendment , which states, “Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States”.

Convict leasing is still practiced in the US to this day, with the majority of working prisoners, who are still overwhelmingly Black and Hispanic, receiving only a few cents per hour. And even upon their release, ex-convicts have always faced immense hurdles to finding employment, getting credit, doing business or buying property due to their prison records.

African Americans were granted full citizenship in the US by the 14th Amendment in 1868, with states being required to provide the same level of legal protection. One response to this was the “separate but equal” ruling in the landmark 1896 case of Plessy v Ferguson, which legalised racial segregation in the public sphere. Homer Plessy, a one-eighth-Black man from New Orleans, had refused to sit in a train car designated for Black people.  , Plessy was arrested and claimed that his 14th Amendment rights were being contravened.

The Supreme Court, in infamous fashion, decided that racial segregation laws were valid as long as the facilities provided to African Americans were of equal quality to those provided to white people.

The Plessy ruling ushered in a raft of so-called “Jim Crow” laws, which reinforced racial segregation across the American South right up until the 1960s. These laws, using a derogatory term for an African American, required separate schools and modes of transportation, effectively outlawed interracial marriage, and authorized the use of “Whites Only” signs to enforce the racist order.

And while the 15th Amendment of 1869 prohibited the federal and state governments from denying citizens the right to vote based on “race, colour, or previous condition of servitude”, it was countered by manipulative practices such as literacy tests, poll taxes and so-called “grandfather clauses” which restricted voting rights to men who had been able to vote or whose male ancestors could vote prior to 1867.

In reality, African Americans received far inferior treatment than the Jim Crow statutes, which in theory intended to “separate but equal” treatment of white and Black peoples. In addition, these laws included societal racism, such as prohibiting the “wrong type” of people from clubs and institutions, city planning measures to ensure that Black people remained on the “other side of the tracks,” and “redlining” by banks where credit was denied to the residents of Black-majority neighbourhoods.

Even places of worship were strictly segregated according to the colour of their congregations. In fact, novelist James Baldwin stated in 1968 that “we have a Christian church that is white and a Christian church that is black,” and that Sunday high noon is the most segregated hour in American life.

All these laws, policies and social attitudes were enforced, frequently with extreme violence, by white supremacist groups such as the Ku Klux Klan, often with the direct or tacit support of the police.

Such were the harsh conditions in which Matilda grew up. Given the prevalence of white male sexual violence against Black girls and women in the south at the time, her childhood abruptly ended when she was 14 years old when she gave birth to the child.

Matilda later entered a common-law partnership with a German-born man called Jacob Schuler and had a total of 14 children, 10 of whom survived into adulthood. The other four’s fate is unknown. Whether she was prevented from marrying her partner by the ban on interracial marriage, or chose that arrangement, is also not known. In any case, Matilda’s financial situation does not appear to have been a result of the relationship because she spent the majority of her working life living in Selma, Alabama. At some point, she changed her surname from Creagh to McCrear, perhaps to distance herself from her enslaver and as an assertion of her own identity. The family surname has evolved into a number of variations, including Crear, Creah, Creagher, and McCreer.

Waiting all her life for justice that never came

In 1931, Matilda was informed of a rumor that people like her were being smuggled into the US illegally as slaves. That was when she decided to embark upon the 15-mile journey on foot to the Selma court in Alabama to make her claim.

The case was dismissed after the judge determined the rumor to be “false.” But fortunately for modern historians, an account of her lawsuit was published by the Selma Times-Journal. Hannah Durkin, a historian at Newcastle University with a focus on the transatlantic slave trade and author of the book Survivors: The Lost Stories of the Last Captives of the Atlantic Slave Trade, discovered this article.

The Selma Times-Journal news story provides a vivid description of Matilda: “She walks with a vigorous stride. Her voice is low and husky, but she is clear and almost white with bright-colored string and tiny tufts. Age shows most in her eyes … yet her … skin is firm and smooth”.

The article continued, stating that “Tildy is a vigor and spirit in spite of her years, and that her innate aptitude for agriculture, inherited from the Tarkar tribe, made her a shrewd farmer.”

Durkin writes that Matilda’s story is particularly remarkable “because she resisted what was expected of a Black woman in the US South in the years after emancipation. She did not wed. Instead, she had a decades-long common-law marriage … Even though she left West Africa when she was a toddler, she appears throughout her life to have worn her hair in a traditional Yoruba style, a style presumably taught to her by her mother”.

Matilda suffered a stroke that caused her to pass away on January 13, 1940, at the age of 83.

One participant at Matilda’s funeral was her little grandson, John Crear. He told National Geographic in 2020 that he nearly fell into the grave when he was three years old after abusing his parents.

John Crear, a retired hospital administrator and community leader now in his late 80s, was born in the house Matilda resided in, and her funeral is one of his earliest memories. The strong character of his grandmother appears to have been woven into family history. “I was told she was quite rambunctious”, he said.

When he and his wife conducted independent family history research, they discovered more about Matilda. “I had no idea she’d been on the Clotilda”, he said. It surprised me really, really. Her story gives me mixed emotions because if she hadn’t been brought here, I wouldn’t be here. However, what she experienced is difficult to read.

Matilda waited all her life for some form of justice and it would be another 14 years before the civil rights movement began to challenge the systemic racism she faced. The 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments’ ideals are skewed by famous figures like Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X, who both pointed out the hypocritical contradiction between the lived reality of African Americans and the ideals of the past.

In a 1964 speech, Malcolm X demanded: “… our right on this earth … to be respected as a human being, to be given the rights of a human being in this society … which we intend to bring into existence by any means necessary”.

Although Matilda was unable to witness any of this, her grandson was a member of the civil rights movement. “You can read about slavery and be detached from it”, he told National Geographic. However, “when it’s your family that’s involved,” it becomes extremely real. During the Civil Rights movement, he was arrested and imprisoned on charges of assault and battery – for the offence of stopping a white man who attempted to stuff a live snake down his throat.

In fact, many civil rights activists experienced severe beatings from the police and the National Guard, which resulted in numerous fatalities, injuries, and imprisonments, as did Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr.

But their sacrifices were not in vain. The entire slew of Jim Crow statutes had been removed by the middle of the 1960s. Segregation in public schools was deemed unconstitutional in the 1954 case of Brown v Board of Education, discriminatory electoral practices such as literacy tests and grandfather clauses were banned by the Voting Rights Act of 1965, and all other forms of segregation and employment discrimination were outlawed by the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

These statutory provisions were intended to eliminate prejudice within the official sphere. However positive their effect, deeper-rooted racism at the societal level remains a feature of US life. Oprah Winfrey, the host of the talk show, said in 2021, “The problem is not solved as long as people can be judged by the color of their skin.”

Ninety years before that, Matilda seemed to recognise this when she seemed unsurprised by the Selma court’s denial of her claim for compensation.

Source: Aljazeera

Leave a Reply