On a chilly afternoon last month in India’s northeastern state of Arunachal Pradesh, Gegong Jijong and hundreds of other protesters gathered nearby the Siang River to chant anti-government slogans.

“No dam over Ane Siang]Mother Siang]”, the protesters in Parong village demanded.

Farmers whose livelihood depended on the water of the Siang River, which cuts through tranquil hills, have regarded it as sacred for generations by Jijong’s ancestors in the Adi tribal community.

He claimed that as India prepares to construct its largest dam over their land, all of that is now in danger.

When finished, the $ 13 billion Siang Upper Multipurpose Project will have a reservoir that can store nine billion cubic meters of water, making it the largest hydroelectric project in India. Officials are now conducting feasibility studies, which were first proposed in 2017.

Locals, however, warn that at least 20 villages will be submerged, and nearly two dozen more villages will partly drown, uprooting thousands of residents.

The Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP)-led state government has mandated the deployment of paramilitary forces to halt protests despite the absence of any clashes as of yet despite the intensifying resistance from locals.

The protesters insist that they are not moving anywhere. “The government is taking over my home, our Ane Siang, and converting it into an industry. We cannot let that happen”, said Jijong, the president of the Siang Indigenous Farmers ‘ Forum (SIFF) community initiative. “Till the time I’m alive and breathing, we will not let the government construct this dam”.

However, the BJP government contends that the protesters are mistaken. The chief minister of Arunachal Pradesh, Pema Khandu, has argued that the Siang River’s true purpose is to be saved rather than just a hydro dam.

From China.

A fragile ecosystem

A geostrategic battle for water and security between Beijing and New Delhi, who are embroiled in a tense rivalry that has occasionally sparked deadly border clashes, is at the heart of the Indian dam project, which Jijong and his community are opposed to.

The Yarlung Zangbo, or Siang River, is located close to Mount Kailash in Tibet. Then it expands significantly and crosses into Arunachal Pradesh. In the majority of India, it is known as the Brahmaputra before falling into the Bay of Bengal.

Last month, China approved the construction of its most ambitious – and the world’s largest – dam over the Yarlung Zangbo, in Tibet’s Medog county, right before it enters Indian territory.

Officials in New Delhi began seriously considering a counter-dam to “mitigate the negative impact of the Chinese dam projects” shortly after China first made its official announcement about its 2020 construction plan. The Indian government contends that the Siang dam’s large reservoir would prevent flash floods or water shortages by reversing the river’s current flow caused by the upcoming Medog dam.

Experts and climate activists are concerned about the presence of two enormous dams in a Himalayan region with a fragile ecosystem and a history of devastating floods and earthquakes, which pose grave risks to the millions of residents who reside there and further downstream. And indigenous communities could suffer disproportionately as a result of India and China’s dangerous power struggle over Himalayan water resources.

Major flashpoint

Even the largest hydro dam in central China, the Three Gorges Dam, will be dwarfed by the new mega-dam in Medog county over the Yarlung Zangbo. China’s government claims the project will be crucial to meeting its goal of achieving a net-zero emission by 2060, and Chinese media reports that the dam will cost $137 billion. On the Chinese side, it is unclear how many people will be forced outright.

The dam’s construction, at the Great Bend near Mount Namcha Barwa, will also be an engineering marvel of sorts. As the water falls into one of the deepest gorges in the world – with a depth exceeding 5, 000 metres (16, 400 feet) – it will generate about 300 billion kilowatt-hours of electricity annually.

The largest new dam is the most recent in a line of smaller dams that China has constructed on the Yarlung Zangbo and its tributaries, according to BR Deepak, a professor of Chinese studies at New Delhi’s Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU).

And these dams “should be regarded as one of the major flashpoints between India and China,” he said, citing the fact that “some of the biggest conflicts have erupted from trans-water rivers.” India and Pakistan’s main conflict is centered on the water in the Indus River tributaries. Ethiopia and Egypt, meanwhile, are locked in a dispute over a giant dam that Ethiopia is building on the Nile.

But India’s response, by constructing a dam over the Siang River, “adds fuel to the fire”, said Deepak. Fears and anxieties will continue to persuade strong responses from lower riparian nations as China continues to dam these rivers.

A report by the Lowy Institute, an Australian think tank, in 2020 argued that control over rivers originating in the Tibetan Plateau essentially gives China a “chokehold” over India’s economy.

The ‘ chokehold ‘

The Yarlung Zangbo has been referred to as the “river gone rogue” in China for many years because it flows southward from the Great Bend to India.

Beijing’s decision to choose this strategic location for the dam, next to the border with India, has prompted concerns in New Delhi.

Saheli Chattaraj, assistant professor of Chinese studies at Jamia Millia Islamia University in New Delhi, said it is obvious that China will have the authority to influence water flows using the dam as a strategic factor in its relationship with India.

Deepak agreed. “Lower riparian like Bangladesh and India will always fear that China may weaponise water, especially in the event of hostilities, because of the dam’s large reservoir”. 40 billion cubic meters of water are anticipated to be stored in the reservoir.

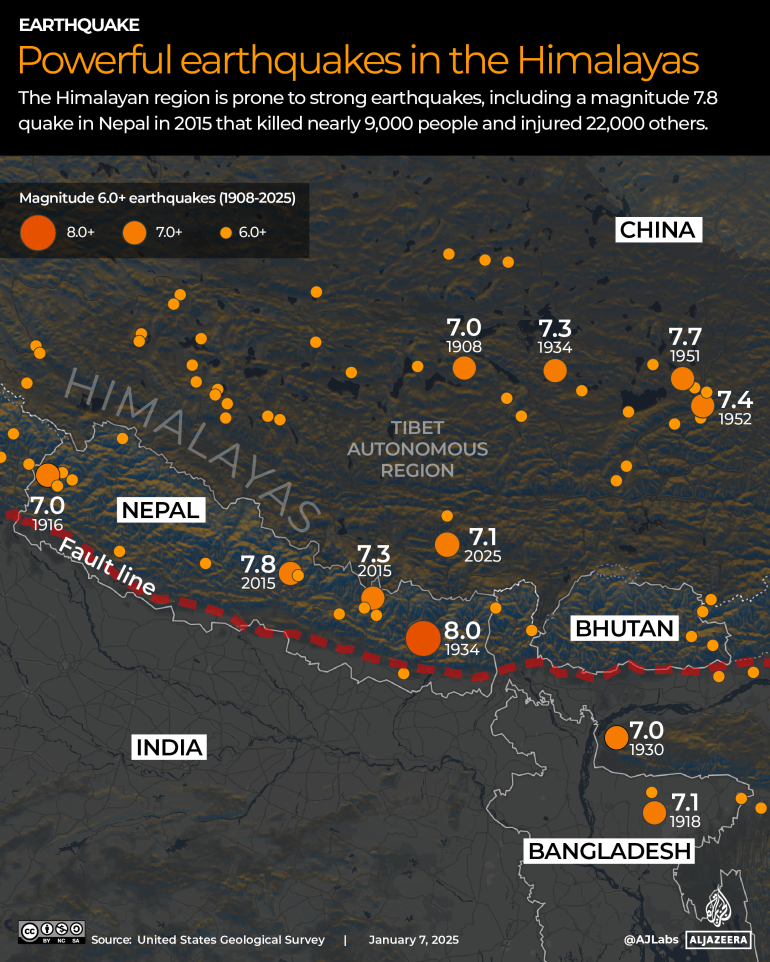

The terrain’s fragility raises questions even more. “The damming of the river is fraught with several dangers”, said Deepak. The Himalayas were the site of about 15% of the largest earthquakes of the 20th century, with a magnitude greater than 8.0 on the Richter Scale.

And Tibet has continued to experience this pattern of significant earthquakes. On January 7, a 7.1-scale earthquake killed at least 126 people. After the earthquake, at least five of the region’s fourteen hydro dams, which were examined by Chinese authorities, showed ominous signs of damage. The walls of one were tilting, while some others had cracks. Three dams were emptied, and several villages were evacuated.

Meanwhile, the Indian government has warned Arunachal Pradesh’s anti-dam protesters that a counter-dam is necessary to reduce the risks of China flooding their lands, using phrases like “water bomb” and “water wars.”

Chattaja, the assistant professor, pointed out that neither India nor China are signatories to the UN’s international watercourses convention that regulates shared freshwater resources, like the Brahmaputra.

Since 2002, India and China have signed a memorandum of understanding allowing the Brahmaputra to share hydrological data and information during the flood season. However, India claimed that Beijing had temporarily stopped sharing hydrological data following a military standoff between the nuclear-armed neighbors in Doklam, which took place close to their shared border with Bhutan. That spring, a wave of floods hit the northeastern Indian state of Assam, leading to more than 70 deaths and displacing more than 400, 000 people.

“It is a problematic scenario and, moreover, when the relationship deteriorates or it is malevolent, like the way it was in 2017, China immediately stopped sharing the data”, said Deepak.

Sour neighbours, bitter relations

The Medog county dam was part of China’s 14th Five-Year Plan (2021-2025), and planning has been under way for more than a decade. However, it was officially announced on December 25, triggering sharp responses from India.

New Delhi has “established user rights to the waters of the river,” according to Randhir Jaiswal, a spokesperson for India’s Ministry of External Affairs, and has “consistently expressed our concerns to the Chinese side” over the size of the projects being done on rivers in their territory.

He added that India will continue to “follow our interests and take necessary steps to protect our interests” and that New Delhi has urged Beijing to “make sure downstream states of the Brahmaputra are not harmed by activities in upstream areas.”

Beijing will continue to communicate with [lower riparian] countries through existing channels and increase cooperation on disaster prevention, according to a spokesperson for the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Mao Ning, two days later. She once more emphasized the importance of the Medog county dam’s contribution to China’s transition toward clean energy and other hydrological disasters.

Yet, trust between India and China is in short supply.

Following a deadly military brawl on the disputed border in 2020, the countries came to an agreement to end their hostilities last October.

But the agreement must not be mistaken for an ice break in sour relations, warned Michael Kugelman, South Asia Institute director at the Wilson Center, a Washington, DC-based think tank. According to him, “there are simply too many points of divergence and tension between India and China, including this most recent flashpoint around water,” he told Al Jazeera.

Kugelman argued that both China and India have suffered from climate change’s negative effects, including water shortages, and that their conflict will only likely get worse over the long run.

“India just cannot afford to see water, which it expects to flow down, be bottled up in China”, he said.

Bangladesh will experience the worst effects.

However, experts claim that millions of people in Bangladesh could experience the worst effects as India and China play a tug-of-war.

Although only 8 percent of the 580, 000-square-kilometre (224, 000-square-mile) area of the Brahmaputra basin falls in Bangladesh, the river system annually provides over 65 percent of the country’s water. That’s why it is viewed as the “lifeline of Bangladesh”, said Sheikh Rokon, secretary-general of Riverine People, a Dhaka-based civil society organisation that focuses on water resources.

“The ‘ dam for a dam ‘ race between China and India will impact us most adversely”, Rokon told Al Jazeera.

For the past ten years, Malik Fida Khan, executive director of the Center for Environmental and Geographic Information Services (CEGIS), has been on guard due to these fears.

“We have access to no information. Not a feasibility report, or the details of the technology that will be used”, he said, his tone tense. “We need a shared, and detailed, feasibility study, environmental impact assessment, and then social and disaster impact assessment. But we have had nothing”.

Before entering the Bay of Bengal, the Brahmaputra directly supports the millions of people who live on its banks, making it one of the largest sediment deltas in the world. According to Khan, “any imbalance in the sediment flow will increase riverbank erosion and potential land reclaiming will disappear.”

India’s dam, Khan lamented, could be particularly damaging to the part of the basin in Bangladesh. “You cannot counter a dam with another down”, he said. Millions of us who live downstream will be seriously and fatally affected.

Rokon agreed. “We need to get out of the ‘ wait and see ‘ attitude regarding Chinese or Indian dams”, he said, reflecting upon the Bangladesh government’s current policy. The Brahmaputra river discussion should be a basin-wide discussion rather than just bilateral discussions between Bangladesh and India or China.

The new dispensation, led by Nobel laureate Muhammad Yunus, has kept its distance from India since Sheikh Hasina’s Dhaka-led government was supported by New Delhi. This also means that there is no joint effort, or a unified pushback, from the South Asian countries to counter China’s growing command over the Brahmaputra river, say analysts.

Whereas Khan sees this water crisis as “a golden opportunity” for India and Bangladesh to forge ties, Kugelman of Wilson Center isn’t optimistic.

“We’ve seen that China is not a country that is receptive to external pressure, whether it be from one country, or two, or even 10”, said Kugelman. It would not be enough to deter Beijing’s actions, even if India and Bangladesh were able to assemble collective resistance against these Chinese actions.

Meanwhile, the threat facing communities on the front lines of these water tensions is only going to grow, say experts.

According to Kugelman, “There cannot be enough emphasis on the significance and seriousness of these water tensions because climate change could make these tensions much more dangerous and potentially destabilizing in the upcoming decade.”

Jijong claims he has no time to rest when he returns to Parong village, a riverside village. He claimed that “we have been making the effects of these dams” more and more people aware.

Leave a Reply