A group of anti-apartheid activists were among the victims of one of the most gruesome murders ever committed in South Africa in 1985, and families of those who were killed by apartheid police are suing the government for compensation in the amount of $9 million.

25 survivors and victims’ families are suing President Cyril Ramaphosa and his government for what they claim was a failure to properly investigate and deliver justice in an apartheid-era case filed at the High Court in Pretoria on Monday.

Families of the “Cradock Four,” who were killed 40 years ago, are among the applicants. They have accused the government of “gross failure” to prosecute the six apartheid-era security officials allegedly responsible for the murders, and for “suppressing” inquiries into the case.

The four – Matthew Goniwe, Fort Calata, Sparrow Mkhonto, and Sicelo Mhlauli – were all anti-apartheid activists from the town of Cradock (now Nxuba) in the Eastern Cape province. They were kidnapped and murdered by police in 1985, causing rage among many Black South Africans, and turning the tide of the fight against racist rule.

However, their alleged killers have all passed away without justice being served.

What are the Cradock Four’s ties to the new case brought against the government thirty years after the end of apartheid?

What happened in 1985?

The four activists were well-known in the Cradock neighborhood for battling the gruesome conditions that Black South Africans endured, including high rent and poor health care. Mathew Goniwe, in particular, was a popular figure and led the Cradock Youth Association (CRADORA). A key component of the group was also Fort Calata.

Prior to the assassinations, apartheid police officers regularly searched CRADORA and detained members like Goniwe and Calata. Officials had also attempted to split them up: Goniwe, a public school teacher, was transferred to another region to teach, for example, but refused to work there and was fired by the education department.

The four were traveling in a vehicle together on June 27, 1985, having just finished rural mobilization work on the city’s outskirts. At a roadblock outside Gqeberha, which was then known as Port Elizabeth, police officers stopped them. The men’s bodies were burned and dispersed throughout Gqeberha after being abducted and assaulted.

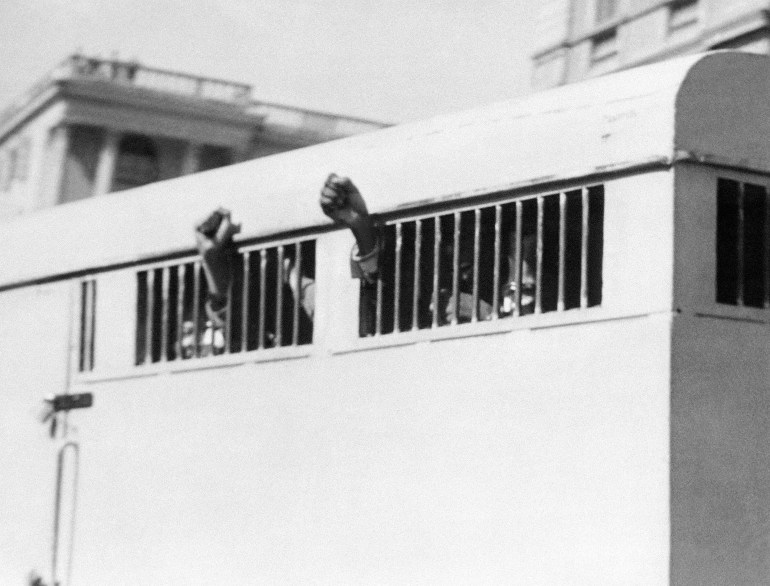

Their deaths sparked Black South Africans’ grief and rage, and they also sparked a significant rise in anti-apartheid activism. Their funeral was attended by dozens of people. With their names on T-shirts and posters, The Craddock Four became household names.

Officials from the apartheid government denied involvement in the killings. The four were killed by “unknown persons,” according to a 1987 court inquest into the case.

However, in 1992, documents that were leaked revealed that Goniwe and Calata, members of the Civil Cooperation Bureau, a government death squad, were on their list of targets. Then-President FW de Klerk called for another inquiry, in which a judge confirmed that the security forces were responsible, although no names were mentioned.

What findings did the TRC make, and why do families feel violated?

Following the fall of apartheid and the ushering in of democratic rule in 1994, the unity government led by the African National Congress (ANC) party launched a Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) in 1996 to investigate, prosecute, or pardon apartheid-era crimes.

The Cradock Four case was one of those reviewed. The commission investigated six police officials who were allegedly , involved. Namely: officers Eric Alexander Taylor, Gerhardus Johannes Lotz, Nicolaas Janse van Rensburg, Johan van Zyl, Hermanus Barend du Plessis, and Colonel Harold Snyman, who is believed to have ordered the killings. By the time of the hearings, Snyman had passed away.

The court ordered the inquiries into hundreds of others, including the Cradock Four’s murderers, whose amnesty was denied, despite the court’s earlier pardons of numerous political criminals. Officials said the men failed to make a “full disclosure” about the circumstances of the killings. To be eligible for a pardon, accused perpetrators were required to fully disclose the events they were involved in by the TRC.

The Cradock Four’s family members at the time expressed their satisfaction with the decision, believing that the South African government would then pursue the accused men. However, successive governments, from former President Thabo Mbeki (1999-2008) to Ramaphosa, have not concluded the investigations, despite the ANC, which helped usher in democracy under Nelson Mandela, having always been in power. Presently, all six accused officials have passed away, with the last man dying in May 2023.

In 2021, the Cradock Four families first sued the nation’s National Prosecuting Authority (NPA) and the South African police, demanding that the court order them to finish their investigations and decide whether the case would be tried in court. Officials did not reopen another investigation until January 2024, which was several months after the last accused official’s passing. Beginning in June 2025, proceedings are scheduled to begin.

To avoid being prosecuted, ANC critics have long alleged that there was a secret agreement between the post-apartheid government and the former white minority government. In 2021, a former NPA official testified to the Supreme Court in a separate case that Mbeki’s administration intervened in the TRC process, and “suppressed” prosecutions in more than 400 cases.

Mbeki denies those allegations. In a statement from March 2024, he said, “We never harmed the National Prosecuting Authority (NPA) in its operations.

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission had requested that the executive not stop the prosecution from pursuing the cases brought before them. If the investigations referred to were stopped, the NPA did not do so at the government’s discretion.

What is the new court case about?

In the new case, victims’ families joined those of the Cradock Four in suing the government for failing to properly investigate their cases. The suit specifically named President Ramaphosa, the justice and police ministers, the head of the NPA and the national police commissioner.

The families are seeking “constitutional damages” to the tune of 167 million rand ($9m), for the “egregious violations” of their rights. In the case of the four Cradock activists, relatives said because government officials delayed prosecution, all the accused officers have died, ensuring that no criminal prosecution would be possible, denying the families “justice, truth and closure”.

Additionally, the families requested that President Ramaphosa appoint an independent commission of inquiry into alleged government interference while he was in office.

Odette Geldenhuys, a lawyer at Webber Wentzel, the firm representing the families in the lawsuit, told Al Jazeera the damages, if granted, would serve as an “alternative” form of justice.

According to Geldenhuys, “over the past 20 years, both victims and families of victims and perpetrators have died.” “The criminal law is clear: a dead body cannot be prosecuted. The ongoing and generational pain will be addressed in some way by alternative justice.

The funds would be available to all other victims and survivors of apartheid-era political crimes, and would be used for further investigations, memorials and public education, Geldenhuys added.

Why is South Africa interested in the case?

The Cradock Four were important figures during the apartheid era, but the fact that their deaths were never fully prosecuted, has held the interest of many South Africans, particularly amid allegations of the post-apartheid government’s complicity.

The left-wing opposition Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF) party sided with the victims’ families and claimed that the ANC government had released convicted murderers, including former assassin Colonel Eugene de Kock, who was sentenced to life in 2015 but was granted parole while serving the Ramaphosa regime.

“The ANC’s handling of apartheid-era violence cases has always been suspiciously lenient”, the EFF’s statement read. It is unacceptable that these families still don’t have any closure or hope for the future of their loved ones after 30 years of apartheid.

In addition to the TRC process, there were a number of other cases that weren’t fully investigated after the lawsuit was filed on Monday. For instance, Housing Minister Thembi Nkadimeng is one of the applicants in the most recent case. Apartheid security forces allegedly tortured and abducted her sister Nokuthula Simelane, who was killed in 1983.

The new case includes survivors of the 1993 Highgate Hotel Massacre in East London, when five masked men shot at people there and stormed into the bar there. Five people were killed, but survivors Neville Beling and Karl Weber, who were injured in the shooting, joined Monday’s suit. No one was ever arrested or investigated. An official investigation started in 2023, and the proceedings will begin this month.

In total, the case could see the deaths of nearly 30 people newly investigated. However, several perpetrators are likely to have passed away.

Source: Aljazeera

Leave a Reply